THE HISTORY OF THE GALLERY

The Hermitage, one of the largest and oldest museums in the world, has come a long way from its position as a "place of seclusion" (the French ermitage, whence its name) in the palace of the Russian' Empress to its present-day standing as an immensely popular national museum. Though in 1778, referring to the Hermitage treasures in a letter to a French correspondent, Catherine II could say: "The only ones to admire all this are the mice and me," and even after it became a "public" museum in 1852 the far from numerous visitors could get admission tickets only from the court office, today the Hermitage is visited annually by over three and a half million people.

The Hermitage

At the present time the museum occupies five buildings, each an architectural masterpiece. Four of these are stretched out in a line on the left bank of the Neva in the center of Leningrad: the Winter Palace, built in 1762 by Rastrelli; the Small Hermitage, designed by Vallin de La Mothe in 1769; the Big (or Old) Hermitage, designed by Velten and completed in 1784; and the Hermitage Theatre, built by Quarenghi and linked to the Big Hermitage by an arched bridge over the Winter Canal. The facade of the fifth building, the New Hermitage, built by Stasov and Yefimov in 1851 from a design by Leo von Klenze, fronts Khalturin (formerly Millionnaya) Street, which runs parallel to the Neva. The portico of the New Hermitage is adorned by ten huge figures of atlantes hewn out of granite by Russian craftsmen under the supervision of Terebenev.

The Hermitage today is virtually a museum of the history of culture - from its very dawn, the Stone Age, to modern times. It consists of six major departments which have on display relics of prehistoric culture (for the most part archaeological finds discovered in the territory of the Soviet Union), the culture of antiquity (including treasures coming from excavations of ancient Greek and Roman settlements on the Northen Black Sea coast), the culture of the peoples of the East (beginning with the ancient civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia), Russian culture, Western European art (painting, drawing, sculpture and applied art), and numismatics (coins, medals and orders). The entire exposition is housed in 353 rooms. Each year the Hermitage stages no less than twenty temporary exhibitions drawn from its own limitless stocks or loaned by foreign museums.

The Gallery

The Hermitage collection of Western European painting enjoys world renown. Most richly represented are the French, Italian, Flemish and Dutch schools, which were especially popular in Russia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the period when the collection was being assembled.

Pictures by famous European masters graced the residences of Russian emperors beginning in the early eighteenth century. In 1716, for example, Peter the Great purchased in Amsterdam for his Peterhof palace a number of works by Dutch artists, including Rembrandt's David's Farewell to Jonathan. A rich collection of European paintings was housed also in the Catherine Palace erected in 1756 in Tsarskoye Selo (now the town of Pushkin).

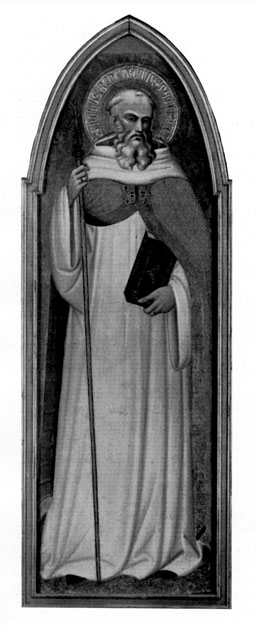

ARETINO SPINELLO St. Benedict

The history of the Hermitage picture gallery begins in the year 1764, when 225 canvases bought a year earlier by Catherine II from the German merchant Johann Ernest Gotzkowsky were delivered to the Winter Palace. This collection consisted for the most part of works by Flemish and Dutch artists and included such famous pieces as Hals's Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Glove, Steen's The Revellers and Goltzius's The Baptism of Christ. This first purchase of pictures was followed by new acquisitions made one after another. Catherine II kept up a regular correspondence with the French encyclopedists Diderot and Grimm, whom she would ask for advice in matters pertaining to the augmentation of her Hermitage collection.

Acting on the Empress's orders, Russian diplomats abroad engaged in the purchase of works of art. In France this assignment fell to the young ambassador Prince Dmitry Golitsyn, a highly educated man, who was to become an honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Golitsyn's many personal contacts and his friendship with the progressive-minded public figures and artists of Paris helped him to carry out his mission with success. He was responsible for the purchase in 1766 of such masterpieces as Rembrandt's The Return of the Prodigal Son and Poussin's Tancred and Erminia. This was followed by the acquisition, also in Paris, of entire collections - Jean de Julienne's, which chiefly included pictures of the Dutch school, in 1767, and Nicolas Gaignat's in 1768. In that same year, also thanks to Golitsyn, the Hermitage acquired for its picture gallery the Hague collection of the Austrian minister Count Cobentzl - forty-six pictures and over four thousand drawings. In 1769, Prince Beloselsky bought for ninety thousand roubles the large Dresden collection of Count Brtihl of Saxony. This minister had been entrusted by the Elector of Saxony with the task of selecting pictures for the Dresden Gallery and had simultaneously put together a sizable collection of his own, preferring works of the Flemish and Dutch schools. Among these were such superb pieces as Wouwerman's View in the Environs of Haarlem and Mieris's Oyster Eaters.

By the end of the 1760s the Hermitage collection of pictures had become too large for the Winter Palace. Additional room for new acquisitions was found in the Small Hermitage, designed by Vallin de la Mothe. This new building consisted of two pavilions (north and south) and a hanging garden between them. Two narrow galleries were added in 1775 by Quarenghi expressly for hanging newly acquired paintings. The north pavilion, which fronts the Neva, was completed in 1769; it had been meant to serve as a "place of seclusion," much like the detached garden pavilions, known as "hermitages," of Tsarskoye Selo and Peterhof (in this case, though, the structure had to be placed in direct propinquity to the palace, not in the garden). Catherine II used to refer to the entire collection of pictures, antiquities, porcelain and gems located in different parts of the Winter Palace and in the adjacent structures (twenty-three years in the building, from 1764 to 1787) as the Hermitage, and it is by this name that the museum has been known since.

ARETINO SPINELLO St.Pontien

The acquisition of pictures abroad was not without its mishaps. In 1771, for example, the Brankarnp collection, purchased in Genoa, was lost at sea together with the ship carrying it to Russia. This loss was, however, compensated for the very next year when through the good services of Diderot and Tronchin the famous Crozat collection (the Thiers Gallery) was acquired in Paris, in spite of objections from the Parisian public. Crozat's collection included works of different schools selected with sound artistic taste and discretion. Among its masterpieces mention schould be made of Giorgione's Judith, Raphael's The Holy Family (Madonna with the Beardless St. Joseph), Titian's Danae, Veronese's The Adoration of the Magi and Pieta, Van Dyck's Portrait of a Young Man, Bourdon's The Death of Dido and Watteau's Actors of the Comedie-Francaise. Purchased at approximately the same time was the small but very interesting collection owned by the French foreign minister, the Duke of Choiseul.

The provenance of some Hermitage pictures, however, is to this day an unclear point. Between 1764 and 1774 the following masterworks of world art found their way into the Hermitage: Family Group by Van Dyck, Flora by Rembrandt, The Marsh by Ruisdael, The Dancer La Camargo by Lancret and Grace Before Meat by Chardin.

Some impressions recorded by visitors to the Hermitage in the second half of the eighteenth century have come down to us. Daniel Bernoulli, connected with the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, mentions a visit to the Hermitage picture gallery in his Russian travel notes of 1777-78. At that time it occupied the Small Hermitage and the two galleries flanking the hanging garden. Bernoulli was dissatisfied with the way the pictures were hung, "without any order or selection, with different schools intermixed haphazardly," but at the same time remarked that "this collection contains some unexpected treasures, some truly priceless pictures." He also reports that visitors were provided with a catalogue issued in 1774 in sixty copies (this first catalogue listed 2,080 works). Another visitor who complained in his diary of 1776 of the indiscriminate way the pictures were arranged and of the cramped and narrow space in the hanging garden's galleries was the French diplomat Gorberon.

The Hermitage pictures were further pressed for space in 1779 with the acquisition in London by Count Musin-Pushkin of the greater part of Sir Robert Walpole's collection from Houghton Hall. This was a sensational purchase, so much so that attempts were made to prevent the collection being taken out of the country. Like Crozat's, Walpole's was a diversified collection and thus a welcome acquisition for the Hermitage because of the long-time preponderance in the museum of Flemish and Dutch paintings. Among the many magnificent canvases that came with the Walpole collection were Rubens's The Carters and The Temple of Janus, Van Dyck's Portrait of Elizabeth and Philadelphia Wharton, Lorrain's The Bay of Baiae, Kneller's Portrait of Grinling Gibbons, Maratti's Portrait of Pope Clement IX, and others.

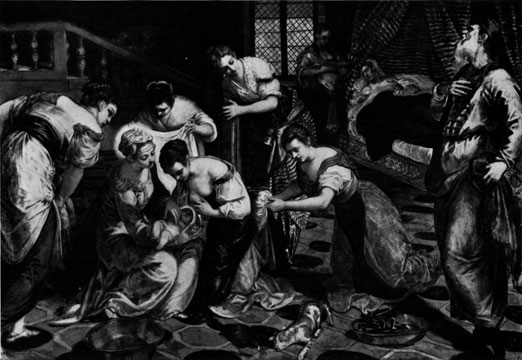

TINTORETTO The Nativity of St. John the Baptist

The last major eighteenth-century acquisition was the purchase in 1781 in Paris of 119 pictures, including nine Rembrandts, from the collection of Count Baudouin.

Another development that contributed to the systematic policy of acquisition at that time was the museum's contacts with contemporary European artists; not only were their finished canvases purchased, but new ones commissioned as well. Thus, in 1766 the Hermitage purchased from Greuze his famous canvas The Paralytic and in 1785 The Blacksmith's Shop from Wright of Derby. Joshua Reynolds, the first President of Britain's Royal Academy, was commissioned by the Russian Imperial Court in 1785 to paint the canvas The Infant Hercules Strangling the Serpents, an allegory of the struggle led by the newly emerging Russian state against her enemies; another Reynolds piece, Cupid Untying the Zone of Venus, was sold by the artist to the Hermitage in 1786. Most of the orders for pictures were placed with French artists - Van Loo, Chardin and Vigee-Le-brun. Chardin executed for the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts the canvas Still Life with Attributes of the Arts, which was brought to Russia by the sculptor Falconet and eventually housed in the Hermitage.

In addition to Imperial collections, the eighteenth century also saw the creation of numerous private collections which boasted some truly superb pieces. Among the best known were the Shuvalov, Beloselsky, Stroganov, Yusupov and Sheremetev collections; many works from these, at one time or another, found their way into the Hermitage or other Soviet museums. Thus, The Madonna from the Annunciation by Simone Martini, that gem of early Italian painting, and Filippino Lippi's The Adoration of the Infant Christ entered the Hermitage in 1911 from the Stroganov collection.

TITIAN Danae

When Velten completed the Big Hermitage in 1784, its first floor was taken over by the picture gallery, a room-to-room guide to which (with even the number of canvases in each room) is to be found in A Description of St. Petersburg published in 1794 by N. Gheorghi. According to the author, there was now more system in the hanging of the pictures which had come to occupy the two galleries along the sides of the hanging garden, the north, so-called La Mothe pavilion, and two suites of rooms in the new building. They were hung so close to each other as to cover the entire surface of the wall; located separately were portraits of members of the Imperial family of the Romanovs and "pictures for copying."

In the same period, two suites of rooms for large-size pictures were added to the south-east corner of the Big Hermitage, as well as a special gallery which was to be a complete reproduction of the world-famous Raphael loggias, painting and all. Catherine II wrote to Grimm in Paris: "I vow to St. Raphael to build a gallery of his loggias, come what may." The copies of the frescoes were commissioned to Christopher Unterberger, and the erection of the gallery to Quarenghi, who completed the Hermitage Theatre in 1785. The entire project took ten years to carry out, and it was only in 1788 that the copies were finally mounted. Of course, from our point of view the work of Unterberger and his assistants cannot be termed an exact copy because they freely filled in the missing parts of the original painting, but even so this was definitely a major event in the cultural life of eighteenth-century Russia.

FRANCESCO MELZI Portreit of a Woman

The Hermitage interiors as they were in the late eighteenth century, and as they remained right up to the building of the New Hermitage, have come down to us in sketches made by Julius Friedenreich between 1839 and 1841. His drawings are arid and formal, but undoubtedly factual.

Information on the growth of the picture gallery in the second half of the eighteenth century can also be gleaned from its catalogues. As mentioned above, the first printed catalogue, in French, published in 1774, listed 2,080 canvases. There is a second, manuscript, catalogue in the archives of the Hermitage, which was put out in 1783 and which carries the titles of 2,658 works. By 1797 the number of pictures in all the Imperial palaces reached 3,996. This figure is taken from an inventory drawn up by a special committee appointed after Catherine II's death to determine the number of art works in her Petersburg and suburban residences. Under Paul I some of the Hermitage canvases were moved to the Mikhailovsky (Engineers') Castle in St. Petersburg and to the palaces in Pavlovsk and Gatchina. Later they were all returned to the Hermitage. In the last decade of the eighteenth and in the early nineteenth century there were only occasional acquisitions, some of them true masterpieces, as The Union of Earth and Water by Rubens.

DIEGO VELAZQUES Portrait of Count Olivares

At the end of the eighteenth century it became necessary to appoint a custodian. The first man to hold the position was Lucas Pfandzelt. He was succeeded in 1797 by Franz Labensky, who occupied the post for over fifty years. Labensky not only acted as keeper, describing and attributing the pictures, but took an active part in replenishing the gallery's stocks. During a trip to Paris in 1808 he bought the famous Caravaggio canvas The Lute Player from the Giustiniani gallery, and in 1810 De Hooch's A Woman and Her Maid in a Courtyard from the Parisian antique dealer La Fontaine. Credit for some of the acquisitions must go to the Director of the Louvre Vivant Denon, whose cooperation was fully in keeping with the traditional ties that existed between the Hermitage and the French capital.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century certain alterations were made in the layout of the Hermitage's rooms. The first "statute" of the museum was drawn up whereby it was divided into five departments, second in the list being "the picture gallery, the chamber of rarities, the bronzes and marbles." A restorers' school was set up in the museum where four artists studied the trade under Andrei Mitrokhin, a Labensky appointee (before that the restoration of pictures had been a matter of experimentation, and not always successful at that).

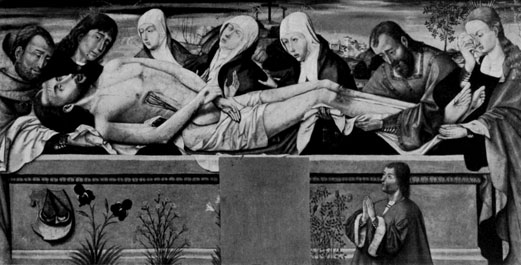

UNKNOWS SPANISH PAINTER Active in the second half the 15 th century. The Entombnent

The normal life of the Hermitage was interrupted by the War of 1812. In the September following Napoleon's invasion of Russia the Hermitage was instructed to dispatch all its treasures by "secret expedition." This order was carried out in the strictest secrecy. Only the record books of the court office contain information on the removal of the Hermitage collections and their return in 1813.

Major acquisitions were made after the war. In 1814, the Hermitage purchased 118 pictures from the Malmaison Palace of the Empress Josephine, the first wife of Napoleon. Among them were magnificent works by Flemish, Dutch and French artists, some of which had been seized as booty by Napoleon in other countries. Such works as The Guard-room by Teniers, Potter's The Farm and Ter Borch's brilliant canvas, A Glass of Lemonade, came to the Hermitage with this collection. In 1829, several more pictures of the Malmaison gallery were purchased from Josephine's daughter, Duchess of Saint-Leu.

Another event that led to a significant enlargement of the museum's Spanish section was the purchase in 1814-15 in Amsterdam of a number of pictures from the Coesevelt collection. These included Portrait of Count Olivares by Velazquez, Portrait of Don Diego de Villamayor by Pantoja de la Cruz and Still Life by Pereda. This nucleus was further enriched in 1834 with the entry of several Spanish canvases from the collections of Gessler, the Russian Consul-General in Cadiz, and Paez de la Cadena, the Spanish ambassador in St. Petersburg. To commemorate Russia's victory in the War of 1812 a special gallery designed by Carlo Rossi was set aside in the Winter Palace to house portraits of the officers who distinguished themselves in that war, much like the gallery in Windsor Castle with its portraits by Lawrence of those who fought in the battle of Waterloo. The Winter Palace portraits were commissioned to the English painter George Dawe. In all, Dawe and his assistants, the Russian artists Golike and Poliakov, executed 329 portraits of military leaders. Pushkin was among the most ardent admirers of the 1812 War Gallery.

BARTOLOME ESTEBAN MURILLO Boy with a Dog

The Hermitage had by then become an important element of Russian culture. Many outstanding artists of the first half of the nineteenth century - Fiodor Tolstoi, Karl Briullov, Alexei Venetsianov, Pavel Fedotov and others - came here to study and copy the works of the Old Masters. However, access to the Imperial museum was still very limited.

In 1837, a great fire destroyed the Winter Palace. It was only at the price of titanic efforts, such as dismantling the passageways and sealing up the door and window apertures with brickwork, that the museum escaped a similar fate. The Winter Palace was rebuilt in a very short space of time, but the reconstruction temporarily diverted the court administration's attention from the Hermitage, which was suffering from an insufficiency of space for its collections: in 1828 the ground floor of the Big Hermitage had been handed over to the State Council and the Committee of Ministers (these premises were reassigned to the museum only in 1855). It now became evident that the construction of a new building for the museum could no longer be postponed.

The edifice was commissioned to Leo von Klenze, the architect who had built the Pinakothek in Munich; the site chosen was the territory between the Winter Canal and the Small Hermitage facing Millionnaya Street plus the courtyards behind the Velten building. Klenze's plan was approved in 1839; the actual construction took about ten years. A special committee, whose leading members were the Russian architects Vasily Stasov and Nikolai Yefimov, was set up to oversee the implementation of the project. The New Hermitage was from the beginning conceived as a museum building whose prime function was to house all the Hermitage collections. The aspect of its halls has been preserved for posterity in the extremely accurate watercolors executed between 1852 and 1860 by Eduard Hau and Lodovico Premazzi.

GEERTGEN TOT SINT JANS (?) St. Bavo

The pictures were selected and their hanging supervised by a committee chaired by Fiodor Bruni, keeper of the Hermitage gallery since 1849. All canvases were divided into three groups: for display, for transference to other Imperial residences and for sale. As a result 1,219 works were auctioned off. It should be noted that similar sales occur in the history of other European museums - the Dresden Gallery and the Munich Pinakothek. Years later, some of the canvases sold in 1854, Chardin's Still Life with Attributes of the Arts, to cite an example, found their way back into the Hermitage.

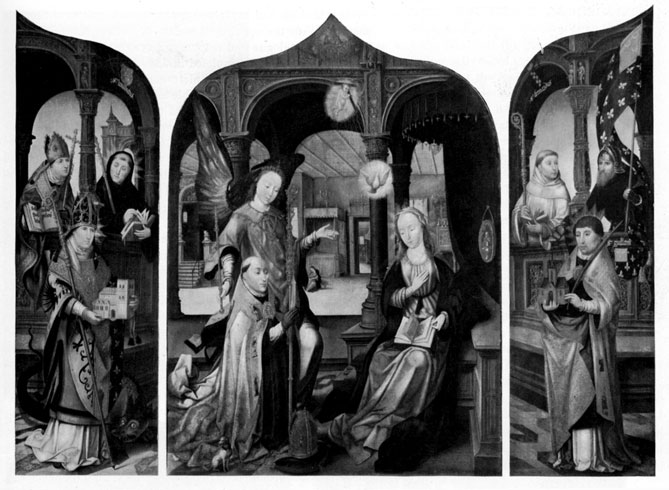

JEAN BELLEGAMBE The Annunciation (trilptych)

On the other hand, important acquisitions continued to be made. Several Titians were bought in Venice in 1850, among them two magnificent canvases, St. Mary Magdalene in Penitence and St. Sebastian. That same year Bruni purchased several pictures at the1 sale of the collection owned by Willem II of the Netherlands, among them Guido Reni's St. Joseph and the Infant Christ. At a Paris sale in 1852 Bruni bought Zurbaran's St. Lawrence, which came from Marshal Souit's collection.

The New Hermitage, proclaimed a "public museum," was opened on February 5, 1852, but a year later the Emperor decreed that "the issue of admission tickets to the Imperial Hermitage and the galleries thereof be entrusted to the court office, not to the keepers of the Hermitage departments." The names of all visitors were to be recorded in a special book.

After the new building of the museum was completed, reconstruction began of the Big Hermitage. The austere interiors created by Quarenghi were redesigned by Stackenschneider as additional palace premises. The reconstruction also took in the La Mothe pavilion, where an impressive but somewhat eclectic hall overlooking the hanging garden was built to replace Catherine's Hermitage.

Twenty-one rooms on the first floor of the New Hermitage were allotted to the picture gallery. The canvases were arranged mainly according to national school, but without any strict system. The last Hermitage catalogue before the transference of the collection to the new building was compiled by Labensky in French in 1838 and contained notes on 1,683 pictures then on display. With the opening of a new exposition the need arose for a new catalogue and a thorough systematization of all the stocks. An inventory completed in 1859 became the main document listing the Hermitage pictures and recording all subsequent acquisitions. Some valuable advice concerning the study of the collection and the layout of the exhibits was offered by Gustav Friedrich Waagen, director of the Berlin Museum's picture gallery, who had been invited for the purpose by the Hermitage authorities. The hanging of the pictures was completed in 1860-61 and by and large remained unchanged up to World War I.

PIETER BRUEGEL I The Fair

In addition to the spacious halls given over to the works of Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Dyck, and to the extensive collections of national schools (for example, the Dutch in the Tent Hall), pictures were also hung in the modest-size rooms adjoining these halls. Displayed in a separate hall were works by Russian artists, among them Briullov's The Last Day of Pompeii and Bruni's The Brass Serpent, to name a few. In 1898 all seventy-two pictures of the Russian school were handed over to the Russian Museum.

Though still subordinated to the palace administration, the Hermitage was gradually assuming the character of a bona fide museum. One of the factors that indubitably contributed to this was the sizable distance separating the exposition from the royal quarters; another was the fact that the personal tastes of the reigning monarch no longer influenced the selection of pictures. In 1863, ninety-nine years after the inauguration of the picture gallery, the first director of the Hermitage was nominated. He was Stepan Gedeonov, head of the Archaeological Commission in Rome prior to his new appointment. Gedeonov greatly eased the restrictions that barred public access to the Hermitage and rescinded the rule whereby only persons in full regimental uniform or tail-coats were admitted to the museum. In 1865, he reported to the palace administration that "steps taken over the past eighteen months to facilitate public access to the Imperial Museum, new acquisitions of important art collections, the issue of catalogues and other like measures had as their consequence an unending flow of visitors to the Hermitage."

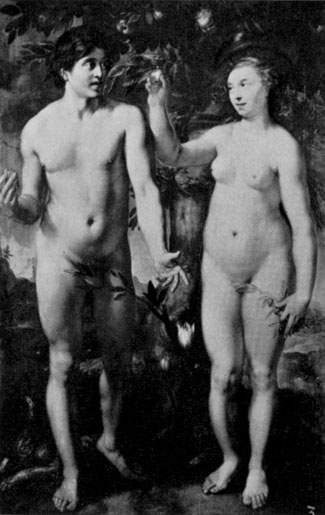

HENDRICK GOLTZIUS Adam and Eve

The Hermitage came to play a major role in the history of Russian culture. However, many of the barriers hindering free access to the museum were still in force. The art critic Vladimir Stasov (son of the architect who built the New Hermitage) expressed the opinion that the museum was not fulfilling its true function. The Hermitage was deprived of all initiative by its subordination to the court office and by a total lack of funds of its own for the purchase of new pictures. Still, thanks to Ge-deonov's untiring energy, Leonardo da Vinci's Madonna and Child was purchased in 1866 from the Duke of Litta's gallery in Milan; and in 1870 Raphael's early canvas Madonna and Child, painted in 1500 for Count Alfano di Diamante, was acquired in Perugia from Count Conestabile. This masterpiece was at first housed in the Winter Palace, but in 1881 was handed over to the Hermitage picture gallery.

Alexander Vasilchikov, who succeeded Gedeonov as director of the Hermitage, also had difficulties in obtaining funds for the purchase of pictures. Nevertheless, in 1882 he managed to acquire in Florence Fra Beato Angelico's fresco Madonna and Child with St. Dominic and St. Thomas of Aquinas, which previously adorned the refectory of the Monastery of San Domeni-co in Fiesole.

FRANS HALS Portrait of a Man

In 1882, the picture collection was enriched by the transfer to the Hermitage of canvases from Peterhof and Gatchina. Among these were Rembrandt's David's Farewell to Jonathan, Van Goyen's Landscape with an Oak, Van Ostade's The Scuffle, Crespi's In a Cellar, Bellotto's New Market Place in Dresden and Tiepolo's Maecenas Presenting the Liberal Arts to the Emperor Augustus. In 1886, seventy-three pictures from the Gol-itsyn gallery in Moscow, amassed in the second half of the eighteenth century, entered the Hermitage.

The beginning of a serious study of the Hermitage collections is linked with the name of Andrei Somov, keeper of the picture gallery from 1885 to 1909. A prominent art historian and an outstanding connoisseur of painting, he devoted much of his activity to the compiling of catalogues raisonnes and to the popularization of the Hermitage treasures, even though the board of directors was opposed to the idea of using the Hermitage for educational purposes. Somov invited two more art experts, Ernest Liphart and James Schmidt, to work in the museum; these latter were especially successful in matters of attribution. Lip-hart, for example, proved that Madonna with a Flower, which entered the Hermitage in 1914 from the Benois collection, was a Leonardo da Vinci work.

ANTHONY VAN DYCK Self-portrait

Among the significant acquisitions made prior to World War I, especially worthy of mention is the large collection of Flemish and Dutch paintings put together by the famous Russian geographer and traveler Semionov-Tien-Shansky, which was purchased in 1910 and brought to the Hermitage in 1915. Of primary importance was the Khitrovo collection of English paintings, bequeathed to the Hermitage by its owner. Its most interesting pieces are portraits by such well-known English artists as Gainsborough (Portrait of the Duchess of Beaufort), Romney (Portrait of Mrs. Greer) and Lawrence (Portrait of Lady Raglan).

On the eve of World War I the number of visitors to the museum amounted to almost 180 thousand a year. The Hermitage of that period was brilliantly described by Alexander Benois in his Guide to the Picture Gallery of the Imperial Hermitage published in 1910. This was a comprehensive assessment of the collection, although the author pointed out that the museum could not be regarded as a manual of the history of culture: certain schools and epochs were well and in many cases superbly represented, but there were also a number of lacunae. In spite of the rearrangement the exposition still had its drawbacks, and its overall character had not changed much in the sixty years of the museum's existence.

The October Revolution made the Hermitage into a state institution which eventually became a museum of the history of world culture. New departments were set up (in particular the Department of the East), but the picture gallery of Western European art lost none of its significance: in fact, it was greatly expanded by the inclusion not only of nineteenth- but of early twentieth-century works as well. Prior to October 1917 the museum had been an annex, as it were, of the Winter Palace; after the revolution it was the Winter Palace that was, at first partially, later entirely, incorporated into the museum as an outstanding architectural and historic monument.

GEORGE DAWE Portrait of Shishkov

On October 5, 1918 the Council of People's Commissars issued a decree on the itemization and preservation of historical and artistic monuments. From the very first days of Soviet power Lenin repeatedly pointed out that the creation of a new, socialist, culture could be based only on the achievements of world culture, which in the past belonged to the ruling classes. The preservation of art works of museum value was entrusted to the State Museum Reserve, which had its headquarters in the Winter Palace. This body's function was to assemble works of art and distribute them among the country's museums. As a result, a number of canvases from nationalized private collections entered the Hermitage, filling in many of the gaps in its stocks, especially as regards nineteenth-century art: Sappho and Phaon by David, Napoleon at Arcole by Gros, Portrait of Josephine by Gerard, Portrait of Count Guryev by Ingres, and others. In 1922, the Academy of Arts turned over to the Hermitage the so-called Kushelev gallery, a collection built up by Count Kushelev-Bezborodko in the 1860s and 1870s. This included Jordaens's Feast of the King of Beans, Delacroix's Lion Hunt in Morocco and Arab Saddling His Horse, Troyon's On the Way to the Market, Millet's Peasant Women Carrying Firewood, Gourbet's Landscape with a Dead Horse and other superb canvases which enabled the museum to have nineteenth-century Western European painting, a very interesting and important chapter in the history of world art, amply represented in its exposition.

KEES VAN DONGEN Lady in a Black Hat

In 1930-31, all the work of the Hermitage was put on a new footing: the museum's pattern of organization was altered, the exposition rearranged so as to stress art's links with history, the picture gallery was provided with additional space in the Winter Palace. A systematic study and detailed itemizatioii of the collections were started. The volume of restoration work was significantly increased. A fruitful period of exchange and cooperation between the Hermitage and the oldest European museums began.

These activities were interrupted by the War of 1941-45. In the very first days of the war the Hermitage collections were taken out of the city and dispatched to Sverdlovsk, deep in the hinterland. The museum staff who traveled with the collections continued their research work even there. Those that stayed behind undertook, under very harsh conditions, the conservation of the remaining collections and of the building itself. In October 1945 all the evacuated treasures were returned to the Hermitage intact and there began the revival and expansion of its exposition, including the picture gallery, which was allotted several more rooms.

The Hermitage collection was significantly enlarged with the transfer to it in 1948 of many canvases from the Moscow Museum of Modern Western Art. The nucleus of this museum had been composed of two famous private collections, chiefly of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century French painting, built up by Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov (several pictures from the museum had come into the Hermitage in 1930 and 1931). It is this transfer that enriched the Hermitage collection with canvases by Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Pissarro, Degas, Cezanne, Vag Gogh, Gauguin, Bonnard, Matisse, Marquet, De-rain and Picasso.

PABLO PICASSO Portrait of Soler

In 1958 a two-volume catalogue of Western European painting in the Hermitage was published listing over four thousand canvases (that is, all the pictures on display plus the finest of the reserve stocks). The catalogue was compiled by the eminent Soviet art historian Vladimir Loewinson-Lessing. In 1964 the Hermitage celebrated its bicentenary. The museum was awarded the Order of Lenin for its contribution to the aesthetic education of the Soviet people.

The staff of the museum continues to do research on the paintings, compile catalogues of pictures of all schools and publish artbooks, scientific papers and guide books. The scope of restoration work has markedly increased, with new methods being used that yield stunning results. For example, an X-ray investigation of the canvas The Adoration of the Magi, earlier thought to be a copy of the Rembrandt original in the Goteborg museum (Sweden), revealed the presence of substantial compositional alterations by the author. This allowed the Hermitage canvas to be recognized as the original and the Goteborg piece as a copy done by one of Rembrandt's pupils. X-ray photography likewise revealed that in Danae Rembrandt removed some of the woman's ornaments to enhance the effect of the golden light emanating from the depths of the picture. It was also discovered that Van Dyck's Portrait of a Man was painted over a sketch of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, that the French artist Lafosse painted his Hagar in the Desert on a canvas that carried a finished male portrait by another artist, and that other monarchs were later depicted over the portrait of Louis XIV in the medallion of The Allegory of Rule by the Italian painter Solimena. The removal of old varnish layers presented some well-known paintings in an entirely new light. The color scheme of Giorgio-ne's famous Judith, for example, underwent a complete transformation after the removal of a layer of dark varnish laid on by antiquarians, and of later overpaintings.

The growth of the museum's collections is a never-ending process. In the last few years the Hermitage has acquired works by French and Italian artists, for example, Bellange, Drouet, Troyon, Boudin, Dufy, Vlaminck, Matisse, Stazione, and Gut-tuso. The Flemish and Dutch sections were enriched by the entry of Teniers and Ostade canvases, the German - by the works of Friedrich and Hans Grundig. The collection of Rockwell Kent's pictures, the artist's gift to the Soviet people, laid the beginnings of the Hermitage's collection of American painting. In 1972, the American collector Armand Hammer presented to the Hermitage the Portrait of the Actress Antonia Zdrate by Goya, a great master until then not represented in the museum. The Hermitage also continues to receive pictures by modern Polish, Hungarian, Rumanian and German artists.

In recent years the Hermitage has hosted many first-class exhibitions of works from the museums of France, Italy, Great Britain, Holland, the USA, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Rumania, the German Democratic Republic, Bulgaria, Japan and other countries, thereby acquainting its visitors with a wide range of outstanding works of world art. On the other hand, exhibitions of Hermitage masterworks in many countries of Europe, Asia and America invariably elicit great interest on the part of art lovers and enjoy wide popularity.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'