Iran

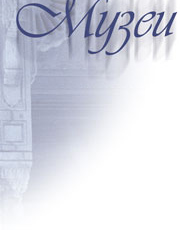

Goddess of Fertility

Susa, Iran. 2nd millennium BC

Stamped clay.

Height 14 cm. lnv. No. 4429 II

Acquired in 1945.

The cult of the Goddess of Fertility, the mother-goddess, was spread among all the peoples of ancient Iran. The high relief representing the goddess gives a summary and schematic treatment of the forms. At the same time certain elements, like the goddess's headdress and ornaments, are treated in greater detail. The soft modelling of the face betrays the sculptor's attempt to convey a certain expression or mood.

Vessels from the Marlik burial

Tepe Sialk, Iran. 10th or 9th century BC

Burnished clay

Height 19.5 cm, diameter 17 cm. Inv. No. 4415 II

Height 19.5 cm, diameter 15 cm. Inv. No. 4416 II

Acquired in 1945.

Pottery-making in Iran has been one of the widest-spread crafts since remote antiquity. Very often it is pottery alone that can cast any light on the earliest history of Iranian art and its relationship with the other cultures of the East. These hand-moulded burnished vessels are striking with their simple and austere forms. Their most conspicuously distinctive features are the spouts shaped like bird-beaks.

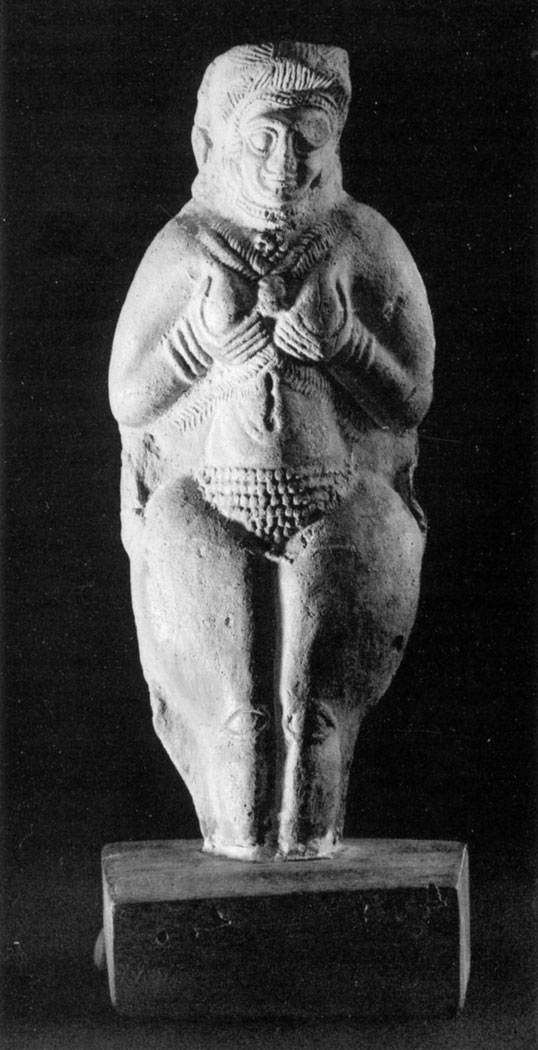

Falcon-shaped vessel

Amlash, North-West Iran. 9th century BC

Carved clay.

Height 19 cm, length 27 cm. lnv. No. 4972 II

Received in 1970 as a gift from the Iranian government.

In the 1950s, an archaeological expedition of the Department of Iranian Antiquities, which was carrying out excavation work in Amlash, a locality on the south-west coast of the Caspian Sea, discovered a large burial near the village of Marlik. Among the finds were gold and silver cups and ceramic wares, including this falcon-shaped vessel. It is characterized by the plasticity of form which is emphasized by a clear and expressive contour. The representation itself is true to life and vivid.

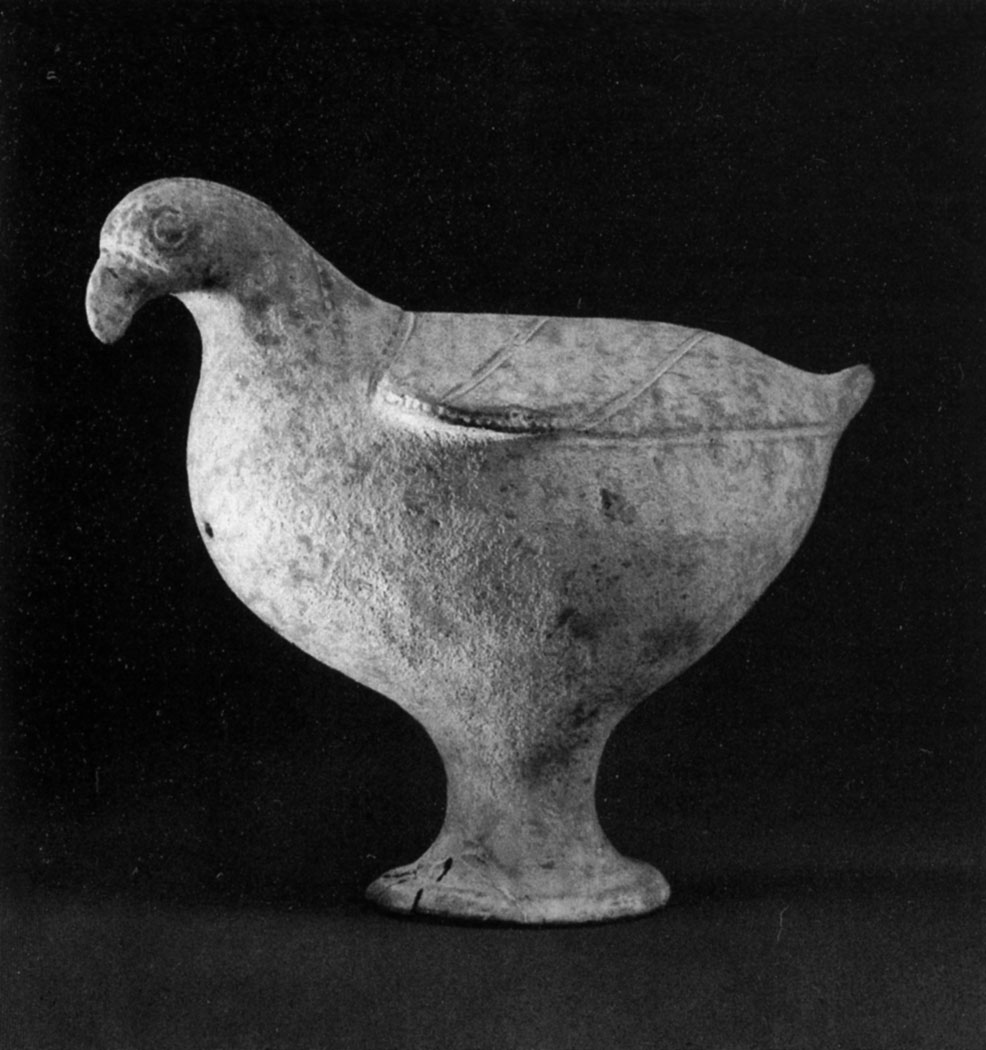

Vessel shaped as the bird Sifvn

Iran. 13th century

Faience with underglaze painting.

Height 27.3 cm. lnv.No.57 II

Acquired in 1918 from the K. Nekrasov collection.

The earliest vessels shaped as animals must have been connected with the ancient cult of nature. During the Middle Ages such vessels continued to appear, but the techniques and the treatment of form were different. These wares stand out among other examples of medieval Iranian pottery. This vessel representing Sirin, the bird with a woman's head, is well known to art experts. The forms, though summarily treated, are yet fairly realistic. This in particular applies to the head in its high headdress. The intricate play of turquoise glaze is enhanced by the black painted pattern. The image of Sirin must have been inspired by Simurgh, a huge bird of ancient Iranian legend credited with possessing great wisdom.

Bowl

Rayy, Iran. 12th century

Faience, painted in enamels and gilded.

Height 8.7 cm, diameter 18.5cm. Inv. No. 729 II

Acquired in 1920 from the K. Nekrasov collection.

Ceramic wares with overglaze painting in enamels fixed by a second firing, the so-called minai wares, came into fashion in Iran in the 12th century. This bowl is one of the finest examples of this type at the Museum. The small figures of people in red, grey and blue clothes stand out boldly against the pale gilded background. The circular composition possesses a rhythmical quality, and the drawing with its clear black contours is well-defined and expressive. Such features, together with the similarities in the repertory of subjects chosen, speak for an affinity between minai pottery and miniature painting.

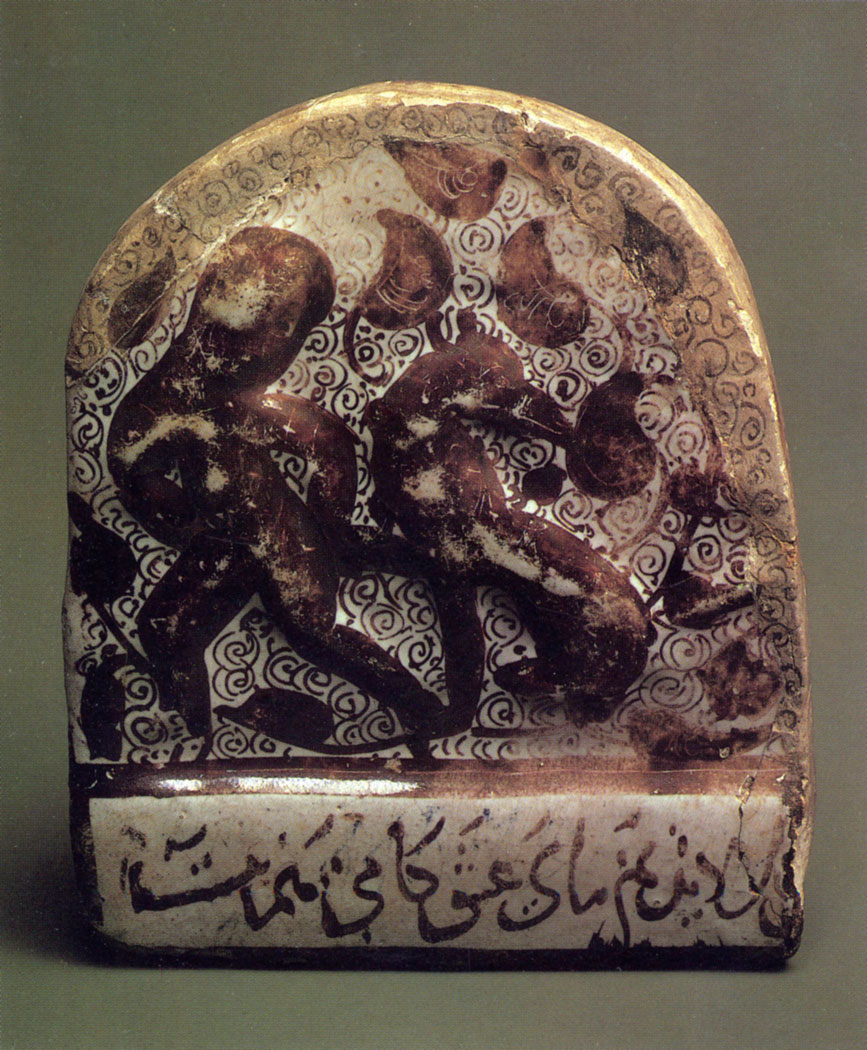

Tile

Kashan, Iran. 13th or early 14th century

Faience, decorated with relief and polychrome lustre painting.

17.1 × 14.3 cm. Inv. No. 1157 II

Acquired in 1928 from the V.Tardov collection.

Tiles were extensively used in Iranian architecture for decorating fagades and interiors of secular buildings, mosques and mausoleums. In the 12th and 13th centuries, lustre-painted tiles were produced on a large scale. They were made in many different shapes: square, cross-shaped or even shaped as eight-pointed stars, etc. Numerous tiles fitted together formed carpet-like facings for the walls of buildings. Each tile was ornamented differently. It might be decorated either with a narrative scene or with a purely ornamental design. Sometimes it might carry lines of poetry or a quotation from the Koran. This tile, showing a boy and an animal, is a vivid example of a well-balanced combination of figure representation, ornamental pattern and epigraphy.

Dervish's bag

Iran. 1879

Steel, inlaid with gold.

Length 22 cm, width 13.4 cm. Inv. No. 971 II

Received in 1926 from the Branch of the State Museum Reserve, Leningrad.

This dervish's bag, or keshkul, is a fine illustration of the superb skill of 19th-century Iranian craftsmen. The treatment of the article is wholly traditional. The ornamentation is arranged horizontally. The upper part is mainly covered with a floral pattern, while the lower band carries quotations from the Koran written in Persian script. The dimly shining gold set off by the steel background enhances the visual effect.

Polonaise carpet

Isfahan or Kashan, Iran. Late 16th or early 17th century

Hand-woven cotton and silk with galloon and silver foil.

161 × 100 cm. Inv. No. 1564 II

Received in 1924 from the History Museum, Moscow (formerly in the P. Shchukin collection).

The carpet consists of several fragments sewn together during its restoration. It belongs to the group of the so-called polonaise carpets, i. e. Iranian carpets of the Safavid period made at the workshops of Isfahan or Kashan for the European market. Since carpets of this group first attracted the attention of art experts and collectors in Poland in the 19th century, they came to be called polonaise carpets. Such carpets were presented by Iranian shahs to European monarchs; they were also commissioned by wealthy European noblemen. The carpets were designed according to the European taste: their strong decorative effect did not depend on the refined composition or elaborate ornamentation, but was achieved through the contrast of rhythms and colours characteristic, for example, of luxury fabrics from Bursa or Venice which were highly valued in Europe. The large palmettes of the carpet are suggestive both of the hotai Islamic motif and of the crown motif in the European style. The surface of the carpet presents a combination of alternating pile and flat sections.

Fabric

Iran. 16th century

Woven silk.

117 × 33 cm. Inv. No. 606 II

Received in 1919 from the History Museum, Moscow (formerly in the P. Shchukin collection).

Fabrics decorated with representational motifs have become widely popular since the late 16th century. At that time court workshops in the largest Iranian cities produced magnificent satins and velvets which found market not only in Iran but in many other countries as well. The rhythmically alternating elements of the composition betray a strong influence of miniature painting, since the designs for such fabrics were often commissioned to miniaturists.

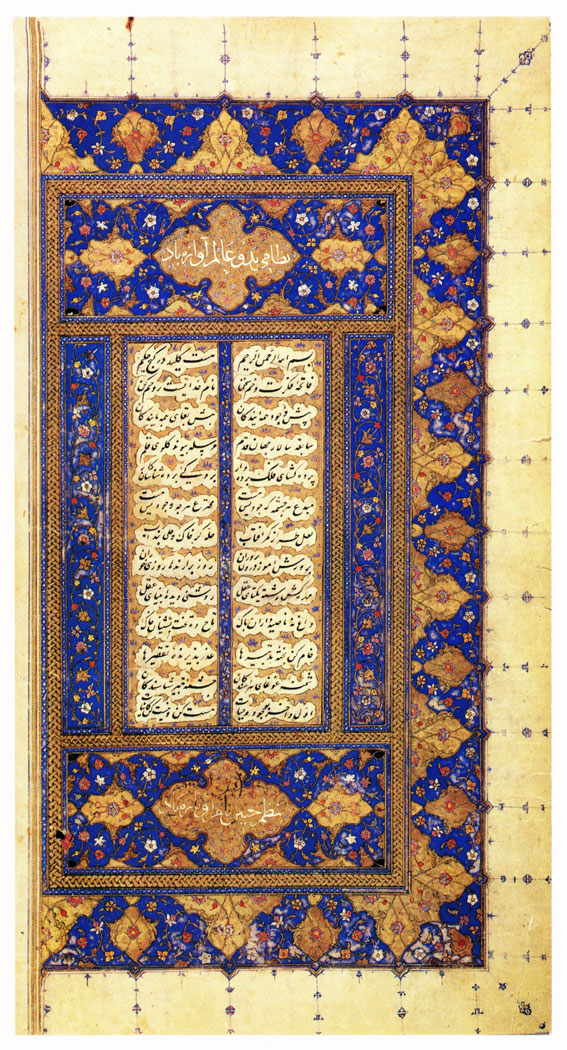

Illuminated sheet from the manuscript of the Khamsa by Nizami

Iran. 1491

28.5 × 16.5cm. Inv. No. 1659 II

Acquired in 1924 from the P. Shchukin collection, Moscow.

Oriental manuscripts excite general admiration by the exquisiteness of their calligraphy, by their colourful illuminations and, finally, by their splendid lacquer and leather bindings.

An Iranian manuscript was usually a joint creation of a calligrapher, a miniaturist and a bookbinder. Sometimes, the calligrapher's work was valued higher and considered more important than the illustrator's work. The anonymous calligrapher of this manuscript undoubtedly possessed a great professional skill. His gracious script looks particularly enchanting in the colourful headpieces.

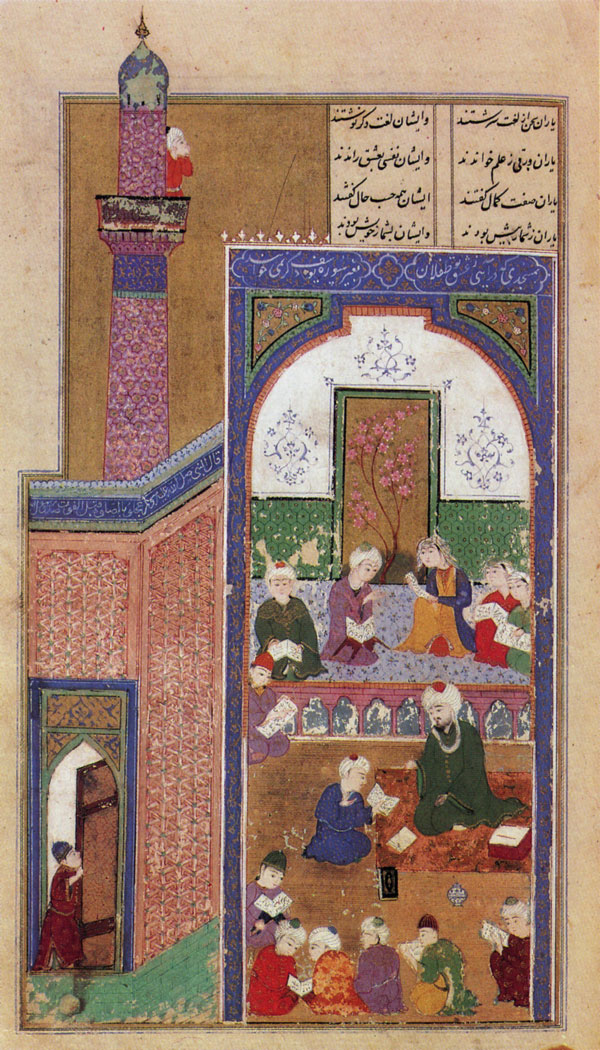

Laili and Majnun at School

Miniature from the Khamsa by Nizami. Iran. 1491

28.5 × 16.5 cm. lnv. No. 1659 II

Acquired in 1924 from the P.Shchukin collection, Moscow. First publication.

The miniature illustrates an episode from Laili and Majnun, one of the most beautiful poems in the Khamsa, or Five Poems, by Nizami. Both the composition of the miniature and its subject are typical of the 15th-century Iranian miniature. The artist skilfully uses traditional compositional principles and imparts a life-like vividness to his picture. The joyous atmosphere created by the scene is enhanced by the brilliant and cheerful colours. The miniaturist meticulously renders various details of interiors, costumes and headdresses.

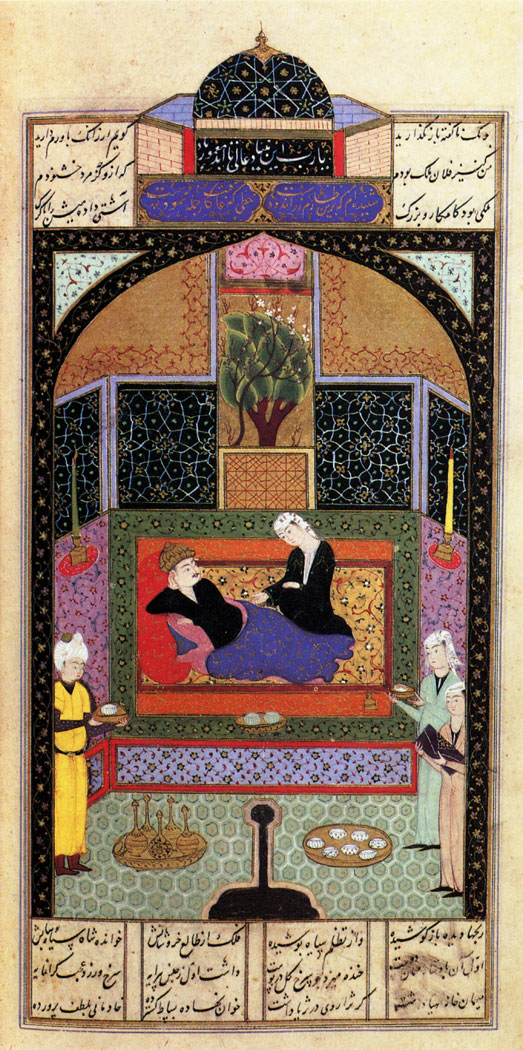

Bahram Gur in the Black Tower with the Indian Princess

Miniature from the Khamsa by Nizami. Iran. 1491

28.5 × 16.5 cm. Inv. No. 1659 II

Acquired in 1924 from the P. Shchukin collection, Moscow. First publication.

Nizami's poem The Seven Beauties tells of Bahram Gur who on each day of the week paid a visit to one of the seven princesses living in the seven towers. All towers were painted in different colours. On Saturday Bahram Gur visited the Indian princess, who lived in a black tower, and spent the night listening to her tales.

All the seven miniatures illustrating the poem are based on the same compositional pattern. The only thing that changes from one miniature to another is the colour of the tower and of the clothes. This suggests that by the late 15th century certain representational canons associated with Nizami's poems had already been formed.

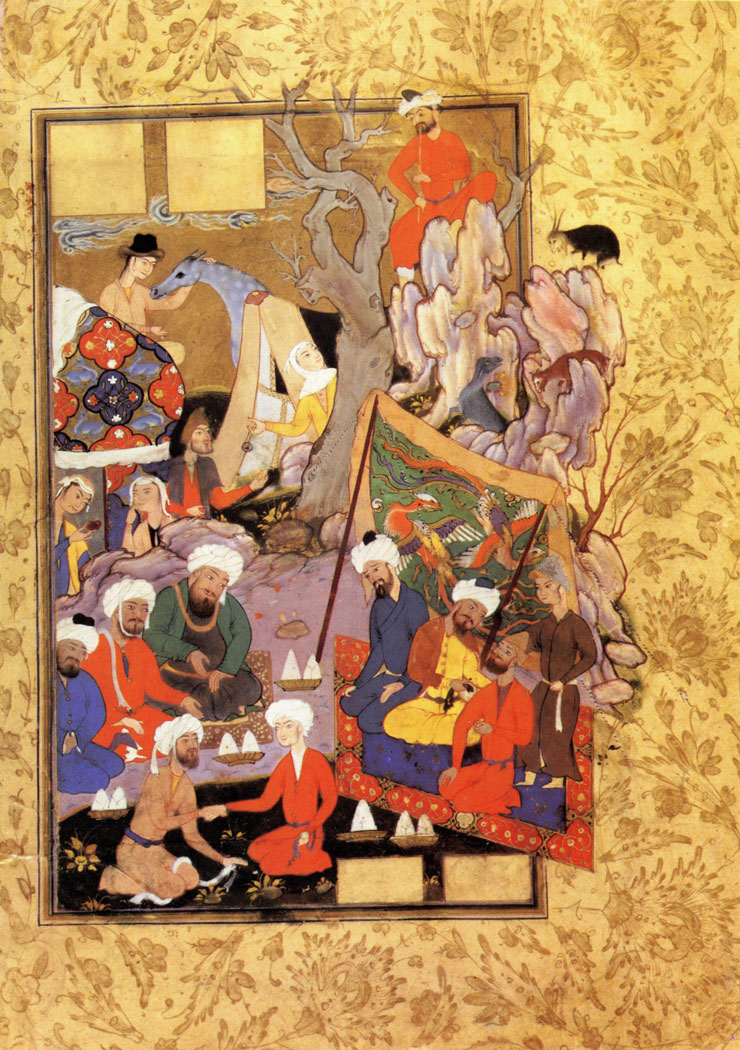

Uaina's Marriage Proposal. Miniature from the manuscript of The Gold Chain by Jami

Iran, Meshed style. 1550s-1560s

24.5 × 15.5cm. lnv. No. 1961 II

Received in 1954 from the Board of Art Exhibitions and Panoramas attached to the USSR Ministry of Culture, Moscow.

The manuscript was written in 1519 by the callig-rapher Mir Ali al-Husayni and later illustrated in the Meshed style.

In the 16th century, Meshed was an important centre of painting. Numerous calligraphers and painters were active at the court of Ibrahim Mirza, a great connoisseur and patron of arts. Miniatures in this style are distinguished by complicated many-figured compositions which, as if short of space, extend beyond the frame of the picture. The margins are decorated with finest floral designs. The palette of these miniatures is strikingly brilliant and picturesque.

This miniature represents a vivid genre scene. Uaina and his future father-in-law are depicted in the foreground. They are shaking hands in token of the marriage contract they have agreed upon. The guests are served with sugar-loaves, which are indispensable attributes of a marriage-contract ceremony.

Miniature from the manuscript of The Treatise on Calligraphers and Artists by Quazi Ahmad ibn Mir-Munshi al-Husayni

1596-97. Iran, Isfahan style. 17th century

24.5 × 15cm. lnv. No. 444 II

Acquired in 1928 from the K. Nekrasov collection.

This miniature demonstrates the changes which had taken place in Iranian miniature by the 17th century. The linear treatment became a dominant aspect of the picture, and the colour scheme, although still fairly saturated, had lost its former brilliancy.

Portrait of an Old Man

By Riza-i-Abbasi. Iran, Isfahan style. 1614

Indian ink on paper.

17.1 × 11.5 cm. Inv. No. 1803 II

Received in 1945 from the Board of Art Exhibitions and Panoramas attached to the USSR Ministry of Culture, Moscow.

The name of Riza-i-Abbasi is associated with a whole epoch in 17th-century Iranian painting whose centre was Isfahan. His creative activity embraced all the new tendencies in the development of Iranian painting and, above all, the painters' aspiration to impart a new meaning to traditional forms and images. In search of new pictorial devices Riza-i-Ab-basi concentrated on the drawing, relegating the colour to a secondary position. The old man is portrayed with a clear and precise line; the treatment of the face betrays the artist's attempt at psychological characterization. He carefully delineates the soft folds in the old man's turban and robe and his beautifully combed moustache and beard.

The inscription in the top right corner reads: "This sketch is completed for my dear son Muhammad Bakir, may Allah prolong [his life], on the 4th of Rajab A. H. 1023. The work is done by the humble Riza-i-Abbasi, may Allah forgive him."

Portrait of Path Аli-Shah. By Mihr Ali

Iran. 19th century

Oil on canvas.

180 × 110 cm. Inv. No. 24914 КП

Acquired in 1974 from the G. Gorbulsky collection.

The leading genre of 19th-century Iranian painting was the formal portrait. Numerous portraits of the Shah, his heir and some epic characters were produced at that time.

Mihr Ali was the chief court painter of the Shah. The portrait shows the sovereign seated on a carpet, in rich clothes and with various insignia of power. This portrait apparently represents a generally adopted canon which the artists were supposed to follow very accurately. The main task of such portraits was to convey the regal grandeur and majesty of the Shah; therefore the artist, even though he attempted a likeness, could not avoid a certain stereotype.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'