India

Kubera

Bengal-Bihar, India. 9th century

Carved stone.

Height 6 cm. lnv. No. 4255 II

Acquired in 1962 from the L. Gelman collection. First publication.

Kubera-the god of wealth-is represented as a fat sturdy man with a bulging stomach. The figurine is in a bad state of preservation, but the attributes of Kubera are still distinguishable: a sack by his left side and two spindle-shaped objects under his feet-either shells or jugs. The statuette is a miniature version of one of large stone stelae which from the 8th to the 12th century (the rule of the Pala and Sena dynasties) were the prevalent type of monumental sculpture in Bengal and Bihar. The front side of such stelae served as a background on which the figures stood out in high relief.

The border of the piece reproduced is framed with stylized flames and the general effect is akin to a halo surrounding the deity (prabha mandala). The god's image is treated in accordance with medieval Indian aesthetic canons, which dictated an almost realistic and true-to-life representation of the human body.

Figure of a woman

Gujarat, India. 15th or 16th century

Carved stone.

Height 104 cm. Inv. No. 5047 II

Received in 1971 from the Board of Art Exhibitions and Panoramas attached to the USSR Ministry of Culture, Moscow.

For many centuries sculpture was the leading art form in India. It was closely linked with architecture and sometimes seemed to prevail over architectural forms proper. During the Middle Ages sculpture was still closely associated with both exterior and interior temple decoration.

This statue from Gujarat (a region in the north-west part of India) presumably comes from a Jaina temple ("Jainism" is one of the three principal religions in India). The temple architecture of Gujarat is characterized by an extraordinary expressiveness and intensity of plastic forms. Judging by the proportions and shape of the stela, it might have served as a console inside the building. The figure is executed in high relief tending towards a sculpture in the round, which is very typical of Indian plastic arts. The woman's face is deprived of any individualized features, while the graceful posture seems to emanate rhythmical motion.

Figure of a woman

South India. 17th or 18th century

Carved ebony.

Height 42.5 cm. Inv. No. 2046 II

Received in 1955 from the All-Union Society for Cultural Exchange with Foreign Countries, Moscow.

The high relief represents a woman in the traditional tribhanga (three bows) posture, in which the head, body and legs are differently orientated. Indian sculptors always strove to convey the beauty and plasticity of the female body. The dancing posture in which the woman is shown here was thought to reveal the beauty and grace of movements to the best advantage. The attitude of the dancer is extremely expressive and dynamically intense. The minutely treated background with its floral ornamentation adds a final plastic touch to the composition.

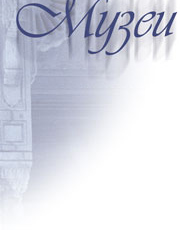

Rama and Hanuman

Relief from Jagannath's chariot. South India. 18th century

Carved teak-wood.

Height 35.5 cm. Inv. No. 850 II

Received in 1924 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow.

This relief once embellished the ritual chariot of Jagannath who is widely worshipped in South India. Once a year, during the festivities associated with this deity the enormous chariot (sometimes as high as a three-storeyed house) was with great ceremony and grandeur driven by the believers from the temple to the city. The entire surface of the vehicle was adorned with wooden reliefs.

The relief reproduced here, one of the thirteen pieces of the same origin possessed by the Museum, represents the characters from the Ramayana-the valiant Rama and Hanuman, his attendant and the chief of the monkey tribe. The composition is executed in high relief and is characterized by an impressive monumentality of forms- a feature typical of Indian stone sculpture. Rama and Hanuman, the favourite epic heroes of the Hindus, had triumphed over the wicked ten-headed demon Ravana and thus became symbols of goodness and valour.

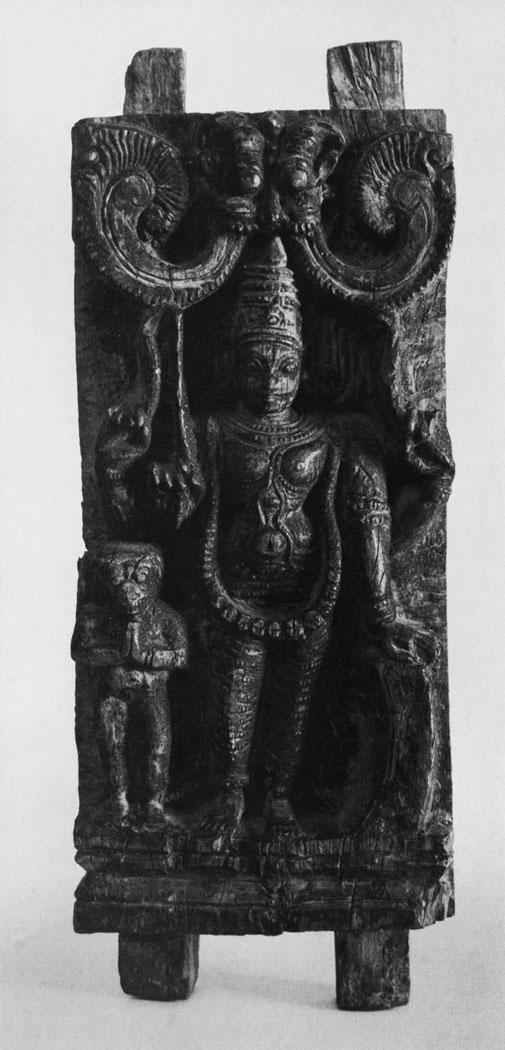

Weapons

India

Dagger. 17th century

Steel, damascened and inlaid with gold.

Length of the blade 40 cm. Inv. No. 2053 II

Acquired in 1935 from the collection of Yu. Berg.

War-axe. 18th century

Steel, damascened and inlaid with gold.

Length of the blade 42.5 cm. Inv. No. 528 II

Received in 1955 from the Hermitage, Leningrad.

Indian armourers have long been known as excellent masters. The weapons which came out of their workshops were always lavishly decorated. The hilts of sabres and daggers were adorned with gems and gold inlays. The chief glory of Indian armourers was damask steel which was highly valued in many countries.

Indian weaponry covers a wide range of different types: daggers, sabres, knives, axes, etc.; but whatever the type, the quality and technical level of metalwork are always equally high.

The weapons were often ornamented with floral design applied by various techniques- delicate incision, gold inlay and so on. The pieces reproduced here are made of first-class damascened steel and richly decorated with gold inlays.

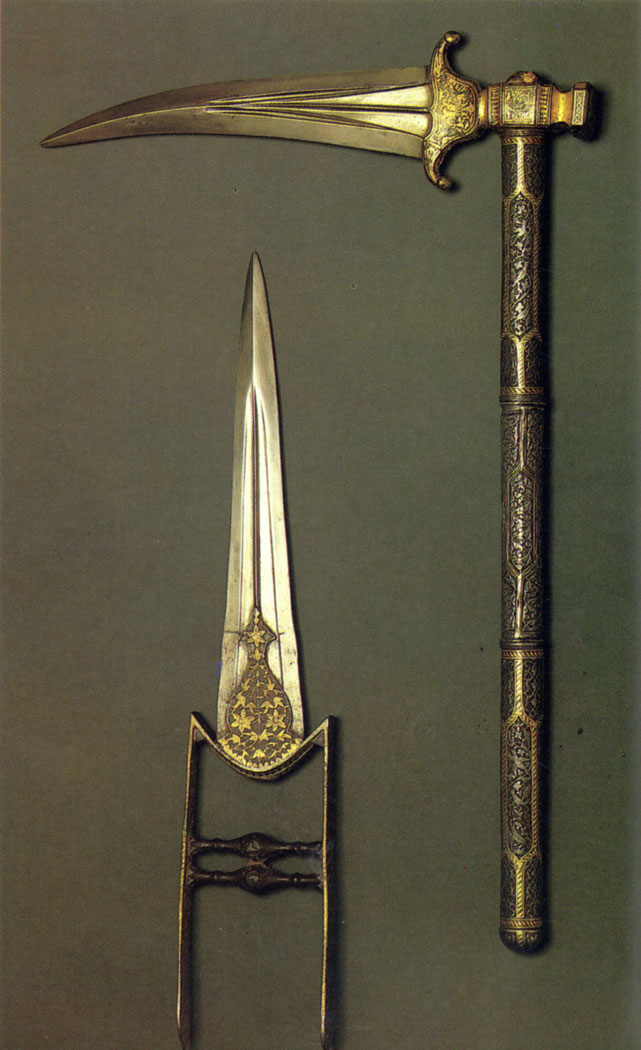

Shield

India. 17th or 18th century

Rhinoceros hide, decorated with gold lacquer painting ; steel protective knobs, enamelled and engraved.

Diameter 43 cm. Inv. No. 2049 II

Received in 1955 from the Hermitage, Leningrad.

This shield made of rhinoceros hide is a great rarity. The method used by the craftsmen to attain the semi-transparent quality and the amber-like sheen of the material remains a secret. Such shields were both elastic and hard enough to ensure a solid protection from arrows and sabres. It is ornamented with a delicate golden pattern evocative of the marginal decoration of Indian and Iranian manuscripts.

Vase

India. 18th century (?)

Copper, engraved, with applied silver repousse decoration.

Height 21.5 cm. lnv. No. 4506 II

Received in 1965 from the Board of Art Exhibitions and Panoramas attached to the USSR Ministry of Culture, Moscow.

Indian craftsmen were renowned for their skilful processing of metal, which was used for the manufacturing of household utensils decorated in various techniques.

The vase in the Museum's collection is adorned with silver plates whose repousse pattern represents figures of dancing women. The copper background is engraved with a minute floral design. The ornamentation of the vase is in perfect harmony with its simple and laconic shape.

Dish

India. 18th century

Clay with underglaze painting.

Diameter 43.6 cm. lnv. No. 1006 II

Received in 1935 from the Museum of Ethnology, Moscow.

The medallion in the centre of the dish represents Krishna, the deity of spring and love, and the beautiful shepherdess Radha. Krishna is playing a flute which possesses a magic power to attract the hearts of all people. The sacred bull Nandi is by Krishna's side. Krishna's figure is much bigger than the other two figures. Krishna was one of the most popular gods of the Hindu pantheon and was believed to live among people on earth.

The medallions along the wide rim of the dish show various epic characters. The composition is supplemented with a pattern of stylized leaves, and the design as a whole is perfectly fitted into the circle, testifying to the artist's skill.

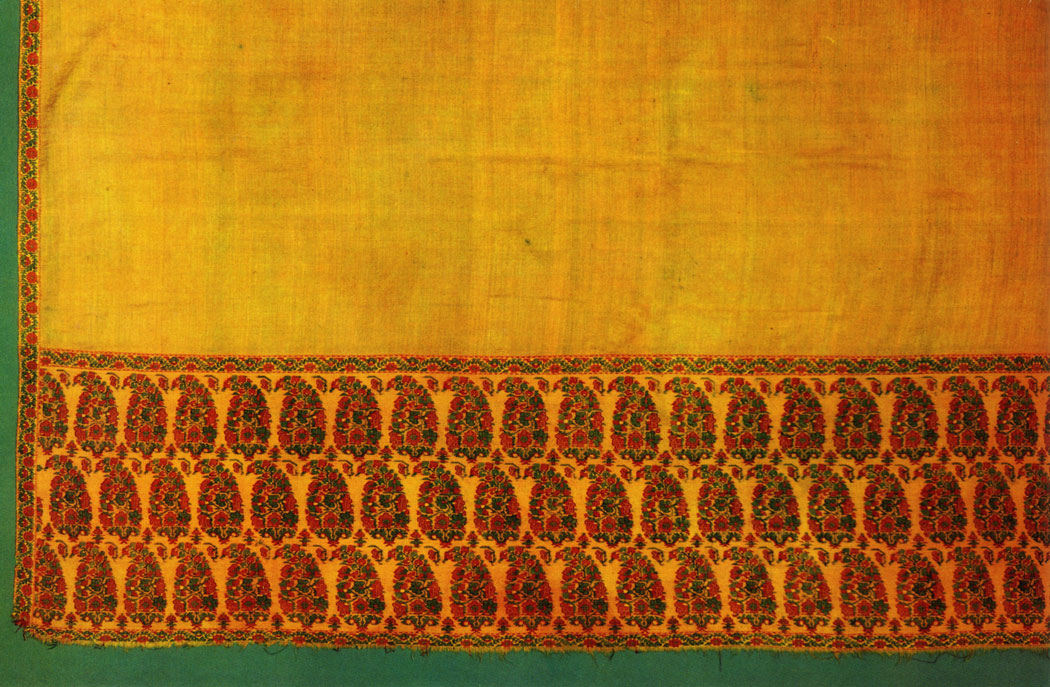

Shawl (detail)

Kashmir, India. Early 19th century

Hand-woven wool.

lnv. No. 6413 II

Received in 1981 from the State Purchasing Commission, Moscow. First publication.

The making of shawls began in the East as early as the 1st millennium BC; in Kashmir it started no later than the 15th century.

This shawl was hand-woven of fine mountain-goat's hair dyed in local natural pigments.

The colour of the main surface of the shawl is striking with its depth and saturation. The border is patterned with a minute floral design. The flowers are grouped to form regularly repeated mango-shaped figures. The pattern is woven into the fabric, which means that the weaver had to use a different weft thread for every separate colour, operating the bobbin like a needle in embroidery. This technique was employed for producing complicated polychrome designs.

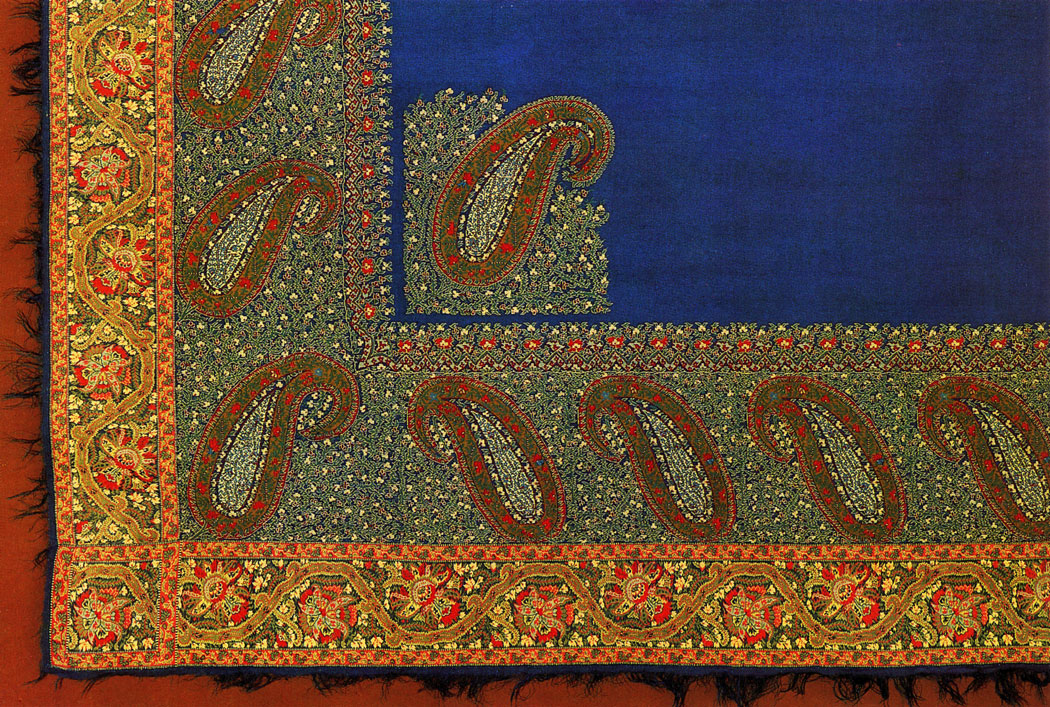

Shawl (detail)

Kashmir, India. 18th century

Wool.

Inv. No. 1765 II

Acquired in 1981 from the E. Sokolova collection.

Kashmir shawls, with their amazing lightness and exquisite floral ornamentation, have long been a recognized model which is still emulated in many European countries.

This factory-made shawl is hardly distinguishable from a hand-woven one. Decorated with the traditional kalki pattern, this shawl, which still retains its natural deep blue colour, is a fine example of the Kashmir weavers' skill and their faithfulness to national traditions.

Shawl (detail)

Kashmir, India. Early 19th century

Hand-woven wool.

Inv. No. 4282 II

Acquired in 1962. First publication.

Shawls of this kind were made in different parts of North-West India, but it was in Kashmir that their production reached the highest artistic level. The secrets of the craft have been handed down from generation to generation of Kashmir weavers for several centuries. The earliest Kashmir shawls had been decorated only with woven patterns, while the ornamentation of the later ones combined woven and embroidered designs, the work being so skilful that the embroidery is practically indistinguishable from the woven pattern. The design was sometimes so complicated that it had to be woven in several separate parts which were then joined together in a fine, almost invisible stitch.

To transfer the pattern for the embroidery onto the fabric, it was first drawn on a sheet of paper, then traced in the outlines with needle-punctures and finally, with the paper over the fabric, it was rubbed through the holes with powdered charcoal. After that the shawl was smoothed down with a piece of agate or cornelian, and only then the embroidering itself could begin.

Bird-catching near Kabul

Miniature from the Babur-nama manuscript. India.

Mogul style. Late 16th century

23.7 × 15cm. lnv. No. 569 II

Received in 1919 from the History Museum, Moscow (formerly in the P. Shchukin collection).

The diary of the Indian ruler Babur (1525-30) contains detailed descriptions of flora and fauna in the countries he visited. The miniatures, which accurately follow the text of the manuscript, illustrate these descriptions with an almost realistic precision. In this miniature the illuminator illustrates an episode described in Babur's diary under 1504/5. The birds can be easily identified as hoopoes, wood pigeons and rollers. The accompanying text describes the method used by the people of Kabul for catching birds: they reel a length of rope on a stick, then, having pulled out the stick, they throw the rope hank at the bird. The inscriptions add a final touch to the overall harmony of the composition.

Babur Entertained by Badi uz-Zaman-Mirza in the Jahan Ara Garden in Herat

Miniature from the Babur-nama manuscript. India.

Mogul style. Late 16th century

26.4 × 15.3 cm. lnv. No. 577 II

Received in 1919 from the History Museum, Moscow (formerly in the P. Shchukin collection).

This miniature illustrates an episode described in Babur's diary under 1506/7. The text on the reverse side of the sheet describes Babur's visit to the Khurasan king Badi uz-Zaman-Mirza. At the feast Babur was treated to a roast goose. He did not know how to carve it, for he had never eaten goose before. Then the host himself skilfully carved the fowl and put the dish before his guest.

Both the composition and the colouring of the miniature are rhythmically balanced.

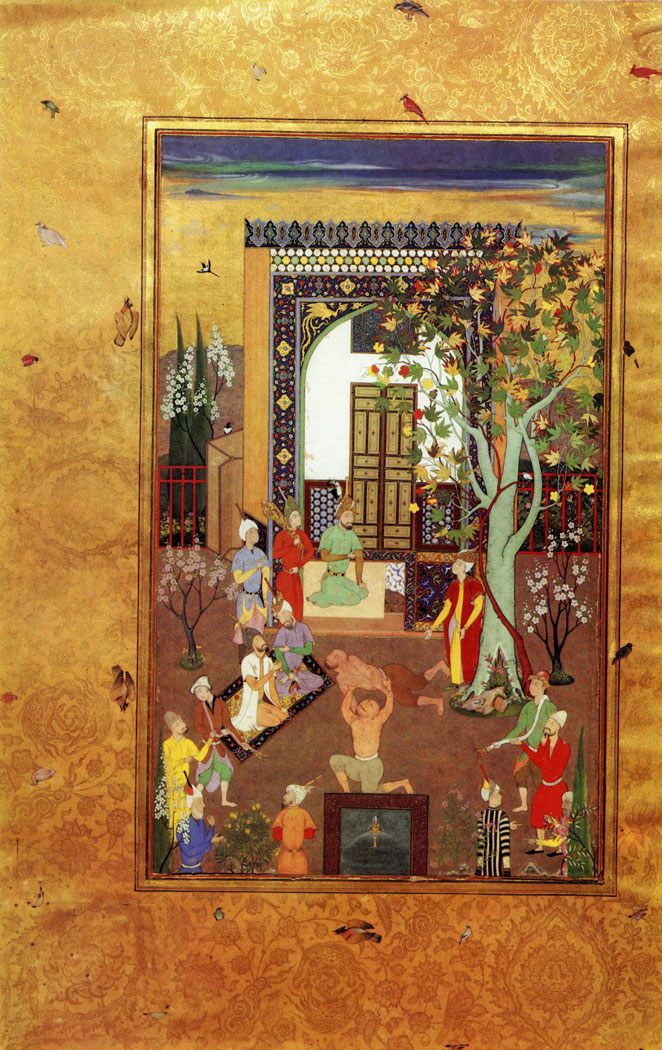

Wrestling Acrobats

By Balchand. Miniature. India.

Mogul style. Late 16th or early 17th century

27 × 16.7 cm. lnv. No. 587 II

Received in 1919 from the History Museum, Moscow (formerly in the P. Shchukin collection).

Balchand was one of the leading illuminators of Jahangir's reign (1605-27). The scene illustrates an episode from Gulistan by Saadi. Once, two acrobats, a teacher and his pupil, were showing their skill at court. The pupil, eager to win, used all the 99 holds taught to him by the teacher. But the teacher used the 100th hold-unknown to his pupil-and defeated the impudent youth.

The miniature shows the influence of Iranian illumination, although on the whole it is definitely a work by an Indian artist with a distinct style of his own. The Iranian influence is mainly felt in the symmetrical composition and in the general decorativeness of the miniature. At the same time its treatment reveals the miniaturist's concern for realistic rendering of the scene and its participants. The representation is still predominantly flat, although certain tentative attempts at perspective in the treatment of space and volume are already apparent. The colouring is really magnificent, and this is probably the most characteristic Indian feature here. The pure local colours in combination with gold create a strikingly picturesque effect.

The reverse side of the sheet bears a specimen of Persian calligraphy signed by Mir All and dated A. H. 938. (1531-32). Mir Ali Haravi was a celebrated 16th-century Iranian calligrapher.

Shiva and Parvati

Miniature. Pahari, India. 1770s-1780s

17 × 23cm. lnv. No. 1996 II

Received in 1954 from the Board of Art Exhibitions and Panoramas attached to the USSR Ministry of Culture, Moscow.

The miniature is remarkable for its extremely well-balanced composition. Against a landscape background the illuminator depicted Shiva, the god of creation and destruction, with his divine spouse, Parvati. Parvati was a symbol of female beauty, and the miniaturist endows her with delicacy and refinement. The picture shows the attributes of Shiva-a crescent on his turban, a third eye in his forehead, a snake round his neck and a leopard skin covering the lower part of his body. A son of the divine couple-the six-headed deity of war - looks out from behind Shiva's left arm. Their second son, the god of wisdom, is represented on Shiva's left side as a child with an elephant's head. The figure in the foreground represents Nandi, the sacred bull. The worship of Shiva and his earthly incarnation as the bull Nandi takes its origin from the pre-Aryan period in deep antiquity.

The landscape, apart from its philosophic and religious message, is a lyrical and realistic picture of nature perceived by a sensitive artist. Miniaturists of the Pahari school knew how to convey sincere feelings and how to relate the beauty of Man and Nature.

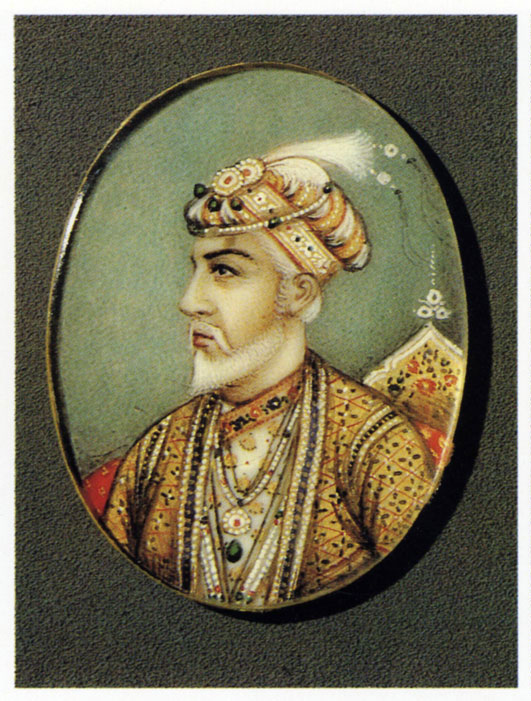

Portrait of Aurangzeb

India. 19th century

Watercolours on ivory.

2.8 × 3.5 cm. lnv. No. 822 II

Received in 1935 from the Department of Museums and the Preservation of Historical Monuments, Moscow. First publication.

Miniature painting on ivory became popular in India in the 19th century. From the 1830s onwards, the Delhi artists painted architectural monuments, portraits of rajahs and court beauties on ivory. Many portraits were commissioned by foreigners, especially the British visitors and residents of India. These miniatures manifest the artists' attempts to combine the traditions of the Indian miniature with those of Western European art. Miniatures on ivory were in great demand, and this art flourished up to the early 20lh century.

The present miniature represents Aurangzeb, a Mogul emperor who reigned from 1658 to 1707.

Portrait of Ranjit Singh

India. 19th century

Watercolours on ivory.

3.5 × 2.8 cm. lnv. No. 818 II

Received in 1935 from the Department of Museums and the Preservation of Historical Monuments, Moscow. First publication.

The miniature shows a ruler of a state under the Punjab government (late 18th century). The portrait is performed with an almost photographic precision, and the model is therefore readily identifiable: Ranjit Singh is known to have suffered from smallpox and to have lost the sight of one eye. The miniaturist took care to show both the pock-marks and the half-closed blind eye of his sitter, as well as other details of his appearance and costume.

Urvaci and Pururavas

By R. S. Sathi. India. 1950s

Paper, mixed technique.

48 × 64.5 cm. lnv. No. 2040 II

Received in 1955 as a gift from the Indian government to the USSR Ministry of Culture.

The composition is based on the legend about King Pururavas who found his wife, the "heavenly maid" Urvagi, who disappeared after spending four years among the people. In the picture the king is asking his wife to follow him back to earth. The idealized mythological characters are treated by the artist as living human beings full of dynamic vitality. The figures themselves are represented in the classical tribhanga (three bows) posture in accordance with the medieval canons of beauty. The artist glorifies the beauty of the human body, its smooth curves and supple forms. Special attention is given to the depiction of hands. The gestures are very expressive and full of dance-like grace. The headdresses, costumes and ornaments are treated with meticulous care and attention to minute details. Clear outlines, subdued colours and an ingenious compositional arrangement testify to the artist's concern for the national artistic traditions.

A Chariot and Sudarshana

By Maqbul Fida Husain (born 1915). India. 1971

Oil on canvas.

121 × 120 cm. lnv. No. 5169 II

Donated by the artist in 1975. First publication.

Maqbul Fida Husain is one of the best-known contemporary Indian painters. His creative career began in 1947 when his works were shown for the first time at an art exhibition in Bombay. Since then his pictures have been exhibited at scores of art shows in different countries and received several national and international prizes. In 1971, Maqbul Fida Husain produced a series of 21 paintings based on the Mahabharata. Using the pictorial idiom of contemporary art, the painter brings the events of the legendary past and the ancient epic ideals nearer to the contemporary perception. The subject of the painting reproduced is symbolic in two ways: a disc, or a wheel, is a symbol of dharma (the universal law of justice and order), and at the same time it symbolizes a missile weapon of Krishna (who is the earthly incarnation of the god Vishnu), directed against evil and evil-bearers (sudarshana).

The painter's works are distinguished by their complicated dynamic compositions and vivid, flickering colours among which blues, yellows and reds prevail.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'