Mongolia

Mask for the Tsam mystery

Mongolia. Second half of the 19th century

Papier-mache, hair, gesso, mineral pigments.

40 × 40 cm. Inv. No. 11443 I

Received in 1949 as a gift from the government of the Mongolian People's Republic.

Of great interest are Mongolian papier-mache masks representing Buddhist deities and mythological characters. These large and heavy masks were worn by Buddhist monks during the ritual Tsam ceremony (the dance of Gods), when they performed dancing and pantomime in the courtyards of large monasteries. The preparation for the ceremony took a very long time. The monks had to learn the complicated movements of the ritual dances; sometimes a single gesture could take several months to learn. The ceremony, which was performed before large numbers of spectators, took place once a year and lasted from midday till late at night. It consisted of twenty-three ritual dances. The masks symbolized the dokshits, or terrifying deities, and contemplative lamas. The appearance of each participant was accompanied with a specific tune. The Tsam masks were kept in monasteries as sacred objects of great value. This mask, shaped as a bull's head with five skulls on top of it, represents the chief dokshit-Chojil. It is made of papier-mache painted with mineral pigments and polished with animal fat. It comes from the workshops of Urga (now Ulan Bator). This fantastic image is vividly expressive and, like other works by the Urga masters, shows the influence of folk applied art.

The White Таrа

Mongolia. 19th century

Cast bronze.

Height 16.5 cm. Inv. No. 3064 I

Received in 1932 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow.

Medieval Mongolian sculpture, like painting, was closely linked with Buddhism. It was strongly influenced by the more ancient artistic traditions of India and Tibet. The anonymous craftsmen, who produced bronze sculptures, followed meticulously the established iconographic canons. One of the Buddhist deities most widely worshipped in Mongolia from the 12th century onwards was Tara, an emanation of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. Tara personified his great compassion for all beings and was a protectress of mothers and children. In accordance with Mongolian custom the believers could address Tara directly, without the mediation of lamas. The goddess symbolized absolute purity. She was usually represented seated on a lotus and with a lotus in her left hand. This flower also figures in the legend dealing with Tara's birth: a tear from Avalokitesvara's eye fell onto a valley and gave birth to a lake; a lotus then rose from under the waters of that lake with Tara in its petals.

The plastic monumentality of the forms, the perfection of the decorative treatment of the pedestal, and the solemn detachment of the goddess are evocative of the national classical traditions.

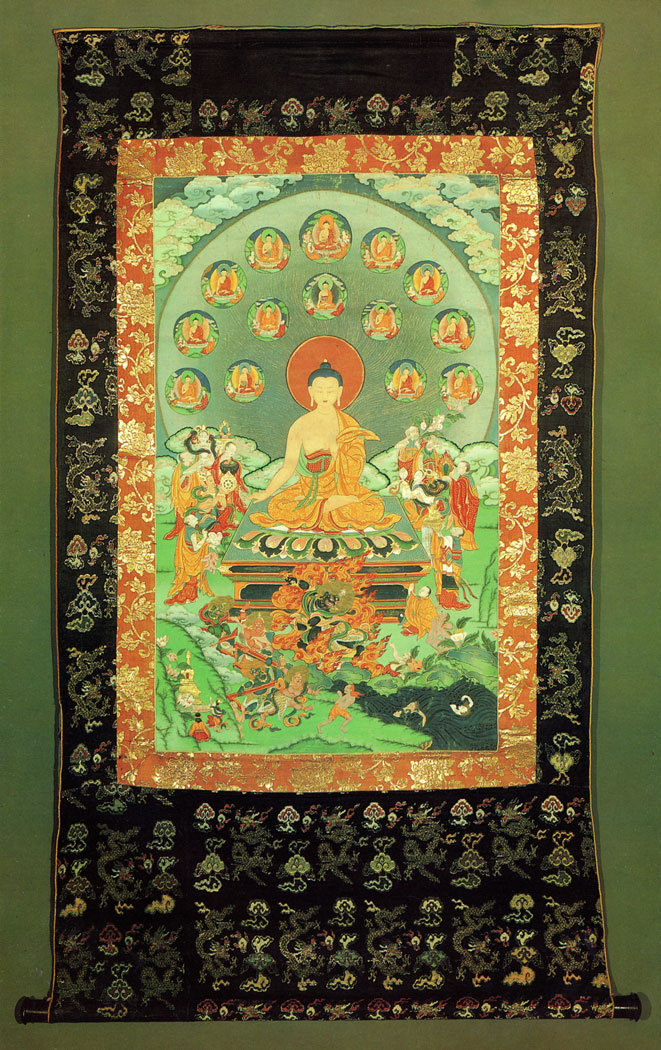

The Sravasti Miracle

By anonymous artist. From the cycle Fifteen Miracles of the Buddha. Mongolia. First half of the 19th century

Mineral pigments on canvas.

45 × 74 cm. Inv. No. 4659 I

Received in 1932 from the Museum of the Peoples of the USSR, Moscow. First publication.

In old Mongolia-a land of nomads, where there were few towns or large settlements-art and artistic crafts were concentrated in Buddhist monasteries. Among the samples of medieval paintings are the thanka icons executed on canvas. The painting of such icons required a special training. An artist's apprentice was supposed to master the complicated iconography of Buddhism. Thus, he had to know, among other things, the 1,000 burkhans (deities of the Buddhist pantheon), each of which was endowed with 32 principal and 84 secondary characteristics. Composition, line and colour had a definite symbolic value. The professional training of the artist took a considerable time. The technique itself was also rather complicated. To protect the canvas from the harmful effects of the changeable continental climate it was carefully grounded and coated with fish-glue or another organic glue. Then burnt alabaster powder was rubbed into the coated surface, and afterwards the latter was polished with a piece of hard chalcedony. At this stage the artist, with the help of a needle and a sketch for the future picture applied to the surface, incised its contour and filled it with powdered pigments. The painting itself was done in mineral colours, including powdered gold, silver and semiprecious stones. In style, old Mongolian painting is related to the Tibetan examples, one of the common features being the symmetry in compositional arrangement. The representation of the deity was conventionally placed in the centre of the composition, with the narrative scenes at its sides. The contours were clearly delineated, and the colours were brilliant and contrasting.

The thanka showing one of the fifteen miracles performed by Buddha in the Indian town of Sravasti demonstrates the artist's adherence to the medieval tradition of hagiographic icons. The subject of the icon is inspired by a well-known Buddhist theme- the Buddha's dispute with false prophets.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'