Japan

Bodhisattva Fugen

Japan. 12th century

Wood, carved and gilded.

Height 115 cm. lnv. No. 506 I

Received in 1919 from the Art and Industry School (formerly the Stroganov Art School), Moscow.

From the 10th to the 13th century Buddhism became a widely practised religion in Japan. Buddhist monasteries and temples appeared all over the country. As these were not only religious but also cultural centres, they became the treasuries of unique works of art and valuable manuscripts. From the workshop of one such monastery comes this statue representing Fugen (the Buddhist divinity of wisdom) astride an elephant. It is stylistically related to the works by Jocho, a celebrated 11th-century sculptor. According to convention, Fugen rests on the lotus-flower pedestal placed on an elephant's back. In comparison with the elephant's heavy body the figure on its back seems almost incorporeal. The rhythm of the hands raised in a conventional gesture of a prayer is echoed by the folds of the drapery. Behind the seeming reserve and austerity of the Bodhisattva one senses deep emotion and spirituality. Fugen, according to the Buddhist iconography, personified the laws of Buddhism. Among his miraculous powers the one most honoured by the Japanese was the power to prolong man's life.

Amida Buddha

Japan. 13th century

Wood, carved and covered with red and gold lacquer.

Height 105 cm. Inv. No. 505 I

Received in 1919 from the Art and Industry School (formerly the Stroganov Art School), Moscow.

The cult of Amida Buddha propagated by the Jodo sect was very popular in Japan in the late 11 th century. Amida Buddha was revered by the Japanese as the lord of the Western Pure Land, access to which was guaranteed by a virtuous way of life and by a mere invocation of his name (Namu Amida Butsu). The tranquil loftiness of the statue and the refinement of its style betray the sculptor's aspiration to convey the idea of spiritual perfection, one of the key concepts of Buddhism. The statue is remarkable for its expressive silhouette and its clear and well-balanced proportions. The stylized draperies and the elaborate shape of the base suggest a measure of deliberate decorativeness. The statue was originally covered with red and gold lacquer but only small traces survive.

Bugaku mask

Japan. 17th century

Wood, carved and lacquered.

18 × 20 cm. lnv. No. 2430 I

Received in 1927 from the Museum of Modern Western Art, Moscow. First publication.

The Bugaku theatre has existed in Japan since the 2nd century AD. It performed mask dance plays which combined ancient Indian, Chinese and Korean dances. In the 8th century, Bugaku dances became part of the Buddhist ritual and were staged at temples. Nevertheless, these mask performances retained a genuinely theatrical character. Bugaku dances represented the safe arrival of ships, battle scenes in which the forces of peace won over the forces of war, ball games and other genre scenes. Mask-making emerged in Japan as an independent craft in the middle of the 6th century. It was connected with the spread of Buddhist Gigaku shows. It was at the time that Gigaku and Bugaku actors started wearing masks for the performances. Among the various characters represented by these masks, magicians and demons were the commonest. The affinity of masks with religious sculpture is manifest in the emphasis on the most characteristic features of the character implied, in their sharply grotesque and powerfully expressive qualities. Despite the conventionality of style, the mask-makers succeeded in creating strikingly vivid images.

The mask reproduced here is highly expressive with its beetling brows, baggy cheeks and its pointed fangs sticking out of the grinning mouth. Many of the Bugaku dances have been forgotten, and the meaning of their complex symbolism still requires clarification, as do many of their icono-graphic and stylistic elements. But the theatre itself is still living and the extant masks have been proclaimed a national treasure in Japan.

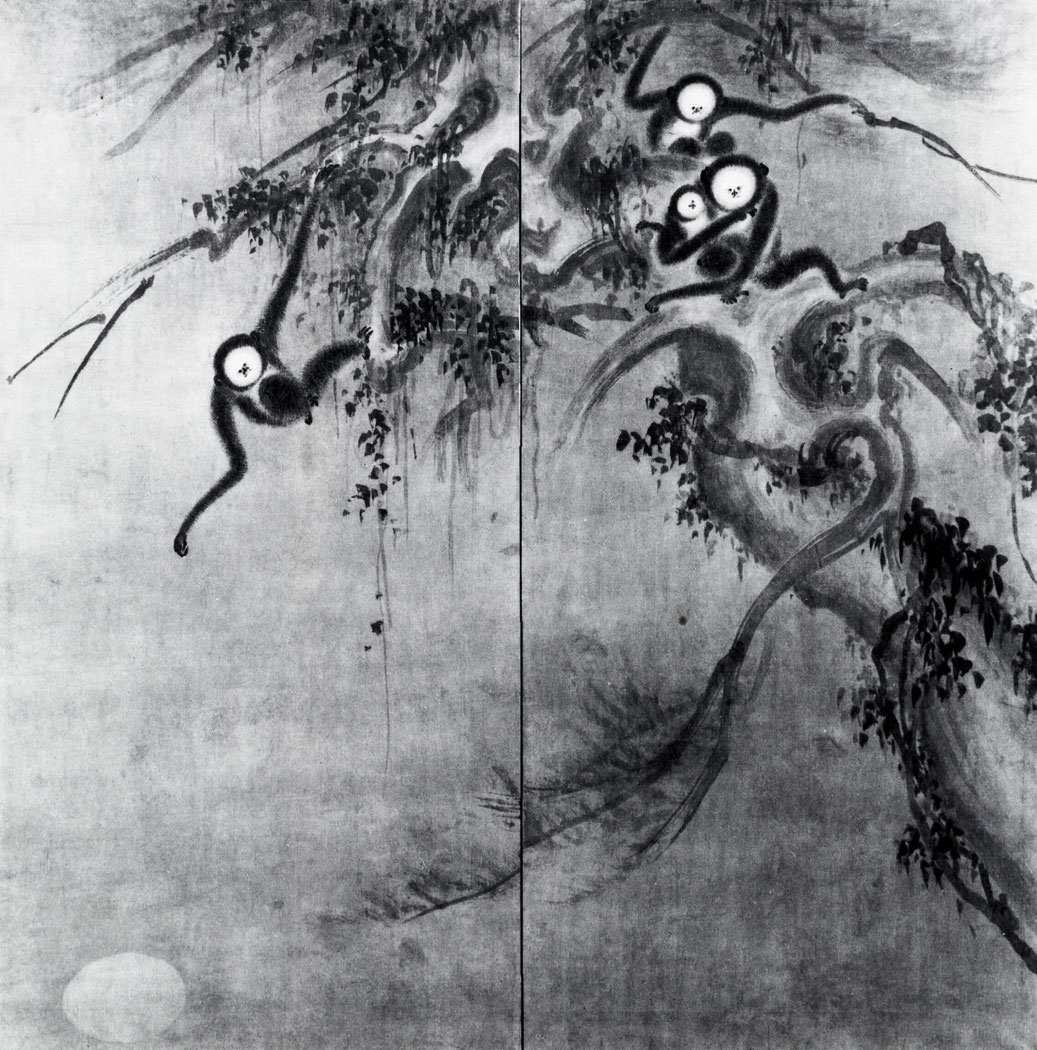

Two-fold screen: Monkeys Trying to Catch the Reflection of the Moon

By Kano Toshun. Japan.

17th century

Indian ink on paper.

Height 185 cm; width 95 cm (each panel). lnv. No. 2489 I

Received in 1928 from the Museum of Modern Western Art, Moscow.

The well-known medieval Japanese painter Kano Toshun was a follower of the Kano school founded in the 15th century. The subjects of the pictures by the artists of that school done, as a rule, on screens and on light movable room partitions, had a religious character.

The composition reproduced here is based on a Buddhist parable about the imperfection of the earthly world and the futility of the pursuit of happiness which is as elusive as the moon's reflection in the water. Kano Toshun's pictures are distinguished by a laconic pictorial manner, summarily treated forms and the free, unrestrained brushwork with soft strokes in ink. Gradations of Indian ink are combined here with barely visible touches of colour, and the predominantly pictorial principle of volume modelling co-exists with the decorative arrangement.

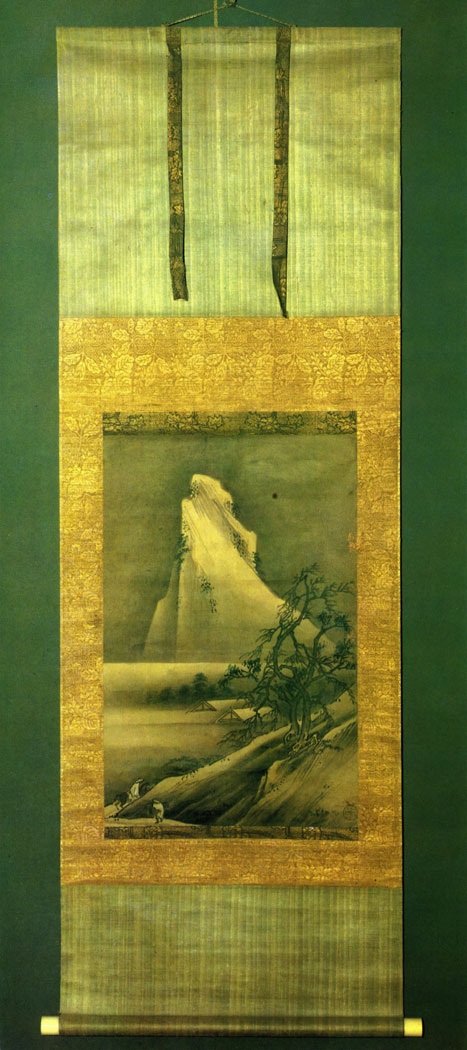

The Falling of Rime-frost

By Hasegawa Nobuharu (1539-1610). Japan

Indian ink and slight colour.

54 × 35 cm. lnv. No. 6592 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow. First publication.

The philosophy of Buddhism inspired suiboku-a style of monochrome painting in ink with light washes of colour used only occasionally, which flourished in the 15th and 16th centuries. The suiboku painting was supposed to put the spectator in a meditative mood and direct his thoughts towards life, cosmic powers, man's place in the world and the correspondence between his deeds and Buddhist ethics. Such a philosophic mood permeates this landscape by Hasegawa Nobuharu. The artist is known as a master of decorative painting. He was born in the town of Nanao (now Ishikawa prefecture). Some art historians believe that Nobuharu is another name of Hasegawa Tohaku. The painter admired the style of the famous Japanese artist Toyo Oda (Sesshu) and even called himself Sesshu godai (fifth-generation successor). His works, however, bear no direct stylistic affinity with his teacher's style: one should rather speak of a deep inner connection. Like Sesshu, Hasegawa Nobuharu endows the philosophic landscape with realistic features and enlivens it with personal feelings and moods. His scroll The Falling of Rime-frost displays a sad and poetic image of nature, an image born in the artist's creative mind. This scroll is the only original work by Hasegawa Nobuharu in a Soviet museum.

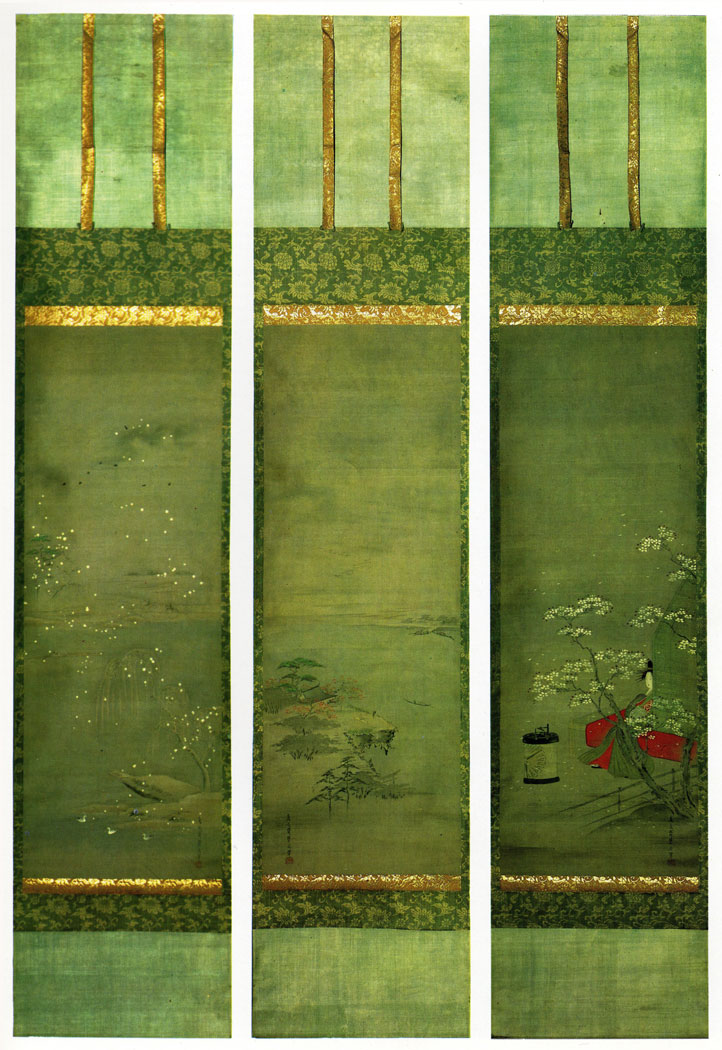

Triptych: Snow, the Moon and Flowers

By Eishi Chobunsai (1756-1815/29). Japan

Colour on silk. 82.5 × 9 cm. Inv. Nos. 6535 I, 6536 I, 6537 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow.

Three motifs from nature, flowers (hanami), the moon (tsukimi) and the snow (yukimi), are sanctified in Japan. Flowers are admired throughout the year with its changing seasons, the beauty of the full moon is to be enjoyed in the autumn and the snow is admired in the early winter. The snow, the moon and flowers have inspired Japanese artists and poets in every age. Eishi Chobunsai was no exception, but he interpreted the traditional themes in his own way, having revealed in his triptych the colourful beauty of the world. The scroll Snow shows weeping willows, ducks floating on the lake and figures of horsemen in the distance. The opaque-white snowflakes stand out boldly against the skilfully tinted olive-grey silk with its delicate washes of colour. In the scroll The Moon we see the edge of a bank with red flashes of maple crowns, a hermit contemplating the moon and a flock of cranes in the sky. The picture evokes a poetic sentiment:

The moon or a morning snow…

Admiring the beautiful, I lived as I pleased.

And this is how I come to the year's end.

The most colourful of the scrolls is the one with flowers. It shows a girl in a grass-green kosode sitting on a dazzling red cloth by the bamboo screen of an engawa terrace. In the foreground there are the famous blossoming cherry trees praised by so many Japanese poets. Snowflakes soaring lightly in the air mingle with cherry blossoms.

Cherry flowers

Seem to have fallen down from the sky-

So beautiful they are.

The spectator looking at the scroll cannot help feeling the artist's admiration of the enchanting beauty of nature.

Bamboo

By Ikeno Taiga (1723-1776). Japan

Indian ink.

130 × 52.5cm. lnv.No.6578 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow. First publication.

Ikeno Taiga was one of the founders of the bunjinga style (literary men's school of painting). Its underlying aesthetic principles were the joy of creative work, individual and original artistic vision and poetical spontaneity. The artist was born in Kyoto, in the family of a fan-maker. His style is characterized by the freedom of self-expression and by its great emotional charge.

Japanese artists praise the bamboo as a symbol of moral purity and nobleness of soul. The roots of this symbolic meaning lie in the similarity between the joints of bamboo stems and the hieroglyph shin (heart). According to the convention, while painting the bamboo the artist strove to reveal the noble proportions of its stalks, to attain a correspondence between the drawing and the background, and to arrange the leaves in a clear rhythmical pattern. Ikeno Taiga's painting exemplifies the tradition in that it displays a deliberate alternation of densely and lightly painted parts, of almost transparent washes and pronounced touches of ink, and finally, of chiaroscuro effects. The dark- and pale-coloured ink is applied in bold strokes; the dynamic composition with its clear rhythmical pattern communicates the artist's feelings.

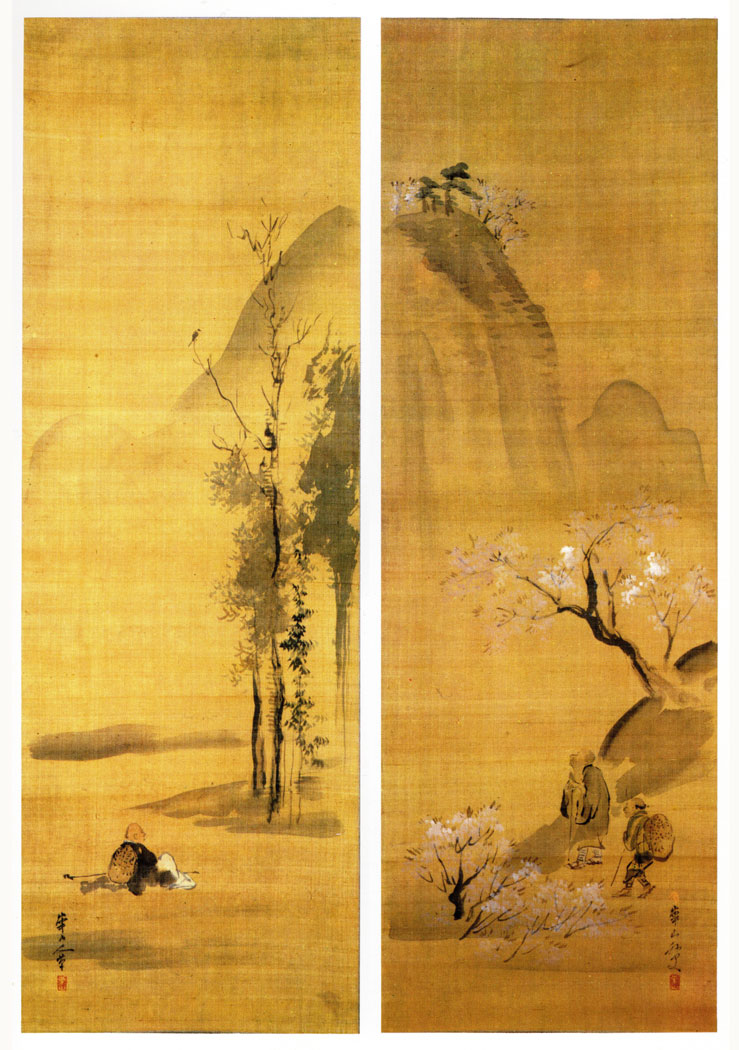

Diptych: Spring and Autumn

By Watanabe Kazan (1793-1841). Japan

Colour on silk.

102 × 34 cm. lnv. Nos. 6637 I, 6638 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow.

Watanabe Kazan, painter, graphic artist, scholar and poet, is an eminent representative of the bunjinga school. He was born in Edo. He was a follower of the celebrated painter Tani Buncho (1725-1794). Watanabe Kazan was also a political figure involved in the movement in favour of the establishment of political, scientific and cultural contact with Western Europe. These aspirations ran contrary to the policy of isolation maintained by the rulers of the Tokugawa dynasty. Watanabe Kazan was arrested for his opposition to the shogun's exclusion policy and committed suicide in 1841.

As a painter, Watanabe strove to unite the traditions of the bunjinga school with certain artistic principles and methods of Western European realistic painting. His landscape scrolls, simple in subject matter and unaffected in composition as they are, impress us with their deep penetration into nature and their emotional richness. Watanabe used the method of contourless drawing, and his favourite medium was the pale-coloured ink supplemented with delicate tinting done in light transparent strokes.

Theatre scene

By Torii Kiyonobu (1664-1729). Japan

Woodblock print, hand-painted.

30.8 × 14.5 cm. Inv. No. 14871 I

Donated in 1965 by Anastas Mikoyan. First publication.

Woodblock printing, which became known in Japan as early as the first centuries AD, reached its acme during the Edo period (1615-1868). It was at that time that prints, which satisfied the artistic tastes of the commoners, emerged as a phenomenon of consequence not only on the national scale, but-also in terms of world art. Prints were used in book illustration, in theatre bills and signboards. The first book illustrated with prints was published in Japan in the early 17th century, but those prints were still indistinguishable from old Buddhist examples. Novel tendencies in the evolution of xylography manifested themselves only in the second half of the 17th and the first decades of the 18th centuries. The centre of the artistic life of the time was Edo, the new capital of Japan. The range of favourite subjects in woodblocks printing encompassed scenes of contemporary city life, where theatre scenes figured prominently, the Kabuki theatre being immensely popular with the people of the capital. Print artists of the Torii school, in particular Torii Kiyonobu, were among the first to turn to the theatrical bill, thus establishing a new genre of printing-pictures of actors and theatre scenes.

This print by Torii Kiyonobu shows the actors Shannagawa and Shegawa Kikunoje performing female parts. The artist concentrated on rendering all the most characteristic features of the episode represented. His style was noted for the dramatic and powerful sweep of curved line. The print of that time was mostly black-lined and hand-coloured. The value of the print reproduced consists in its having been coloured by the artist himself who used subdued olive, beige and yellow hues. The colour was still but a modest accompaniment to the principal motif conveyed by rhythmic lines.

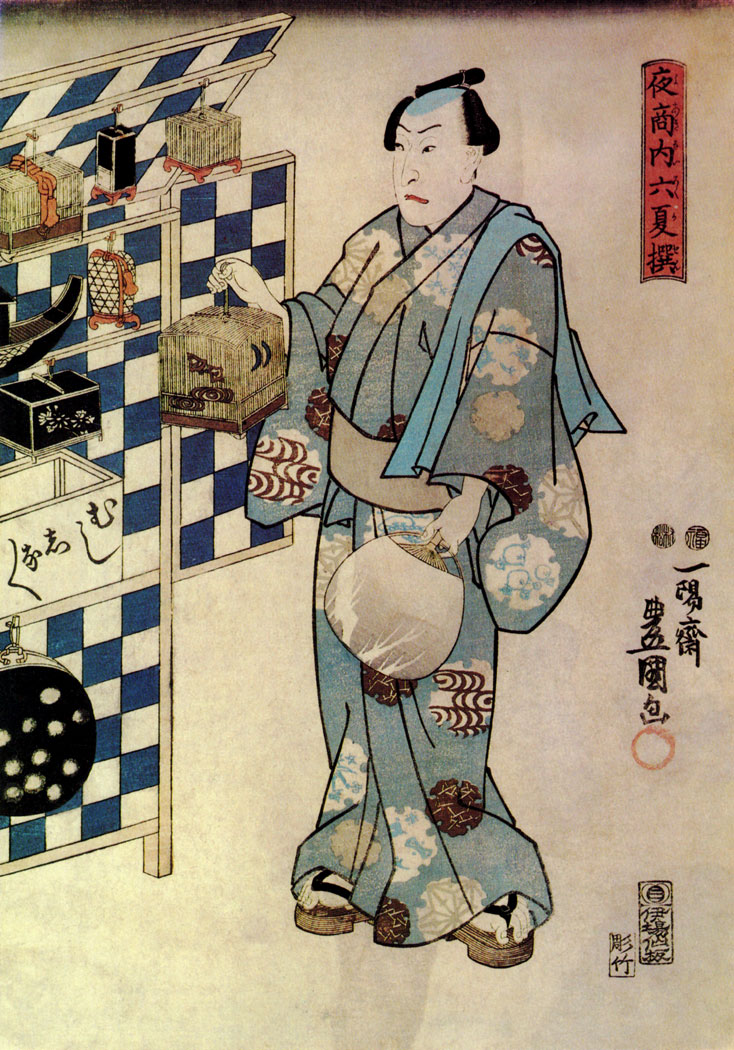

Actor as Cricket-seller

By Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825). Japan

Woodblock print, hand-painted.

25.5 × 36.5 cm. Inv. No. 961 I

Received in 1926 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow. First publication.

Utagawa Toyokuni (originally Kurahashi) lived and worked in Edo. His father was a famous puppet-maker, consequently his association with the Kabuki theatre began when he was still a young boy. Utagawa Toyokuni's artistic work developed the well-established traditions of Japanese woodblock printing, with its close relationship to the theatre. The distinctive feature of his prints, however, consisted in their more pronounced realistic and true-to-life character. The artist often portrayed the actors both in their stage roles and in their everyday surroundings, concentrating on the accessories of their life and profession and paying much attention to clothes and various characteristic details. This print shows an actor holding a box with crickets, and even though the market-place as such is not represented in the picture, its atmosphere is strongly felt, and it is easy to picture the grave-looking cricket-seller advertising his goods. Contrast of basically subdued colours and accents of brilliant paint is used by the artist to intensify the emotional expression. This and other prints by Utagawa Toyokuni reflect a great decorative sense typical of later Japanese woodblock printers.

Sketches

By Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Japan

Indian ink.

24.1 × 34.1 cm. lnv. No. 8882 I

Acquired in 1952 from a private collection. First publication.

The famous Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai came from a low-class urban family. His life and creative career was linked with Edo. He was trained as an engraver under Nakayama Tetsuson (18th century), and learned to design actor prints from Katsukawa Shunsho (1726-1792). Hokusai's creative work embraced a broad variety of art forms. He worked primarily as a painter and was one of the great draughtsmen of the world. He also produced surimonos-deluxe prints made for special occasions, designed fabrics, fans and combs, illustrated books and painted hanging scrolls and screens. The outcome of his long career amounts to about 30,000 drawings and prints and some 500 illustrative volumes many of which are still extant. He was among the first artists who introduced landscapes into his works. For Hokusai the landscape was first and foremost a setting for human activity. The artist was primarily interested in people's everyday life and work. Hokusai travelled extensively, entrusting all his impressions and observations to ink and paper. He was responsible for the emergence of a new aesthetic concept-shinrabanshe ("a forest of forms", or the "ten thousand phenomena")-according to which everything in the world was worthy of the artist's brush.

This sheet with drawings done by Hokusai's own hand is an exhibit of unique value. It represents samurais engaged in a conversation and two actors at rest. The right-hand part of the sheet is taken by close-ups of their faces. The vigorous and energetic line, together with a generalized manner in which they are done, endows them with a highly expressive quality.

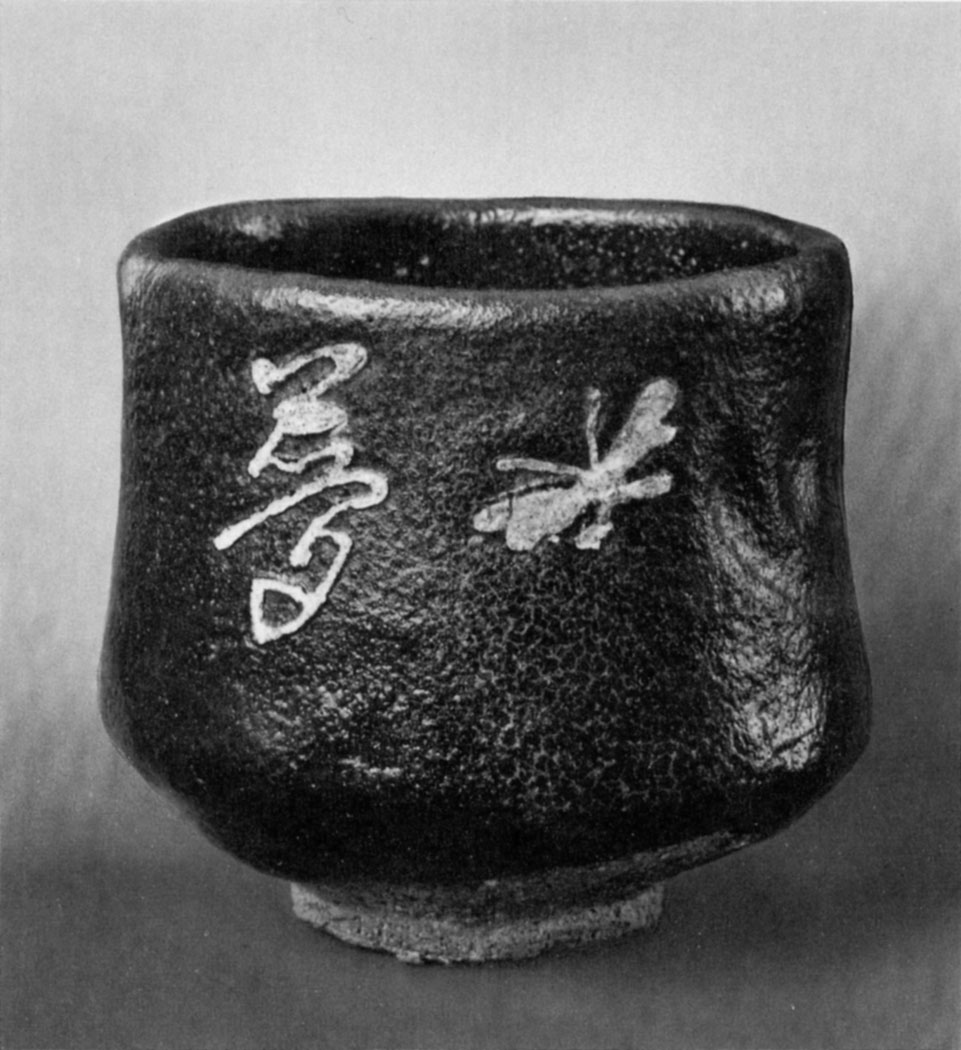

Chawan bowl for the tea ceremony

Kyoto pottery, Japan. 17th century

Glazed clay.

Height 9.5 cm, diameter 9.8 cm. Inv. No. 15242 I

Received in 1957 from the History Museum, Moscow.

The development of Japanese ceramics in the 16th and 17th centuries was directly associated with the tea ceremony (chano-yu) whose complicated etiquette was based on the Buddhist concepts of the unity of man and nature, of the harmony between man and material world, of complete equality in the face of beauty, of the tranquillity of feelings and of the absolute purity of mind. New rules for the tea ceremony permitted the intellectual appreciation of art and literature in the company of like-minded persons over a bowl of tea. The establishment of chano-yu conditioned the appearance of special tea utensils-cha ki-the majority of which were made of clay. Each utensil used, and every movement, down to the smallest gesture, was required to be beautiful and aesthetically pleasing. Special attention was given to chawan-the tea bowl. Its shape and colour scheme determined the choice of the other tea utensils.

This tea bowl is made in the raku (joy) style. It is produced of coarse-texture clay. A thin coat of lustrous black glaze only partially covered the bowl, leaving some of the surface exposed. These exposed parts are decorated with an ideograph and a butterfly symbolizing joy. The bowl was shaped by hand with deliberately added irregularities. The potter managed to bring out the plastic potentialities of the material in full accordance with the motto of Japanese craftsmen: "Do not invent but reveal the essential quality of the material used."

Flower vase

Iga pottery, Japan. 17th century

Glazed clay.

Height 27.5 cm, diameter 12.5 cm. Inv. No. 15304 I

Received in 1967 from the History Museum, Moscow.

The Iga vase with its heavy and crudely potted body symbolizing the solidity of the earth must have been conceived by the potter as a contrast to the fragility of flowers.

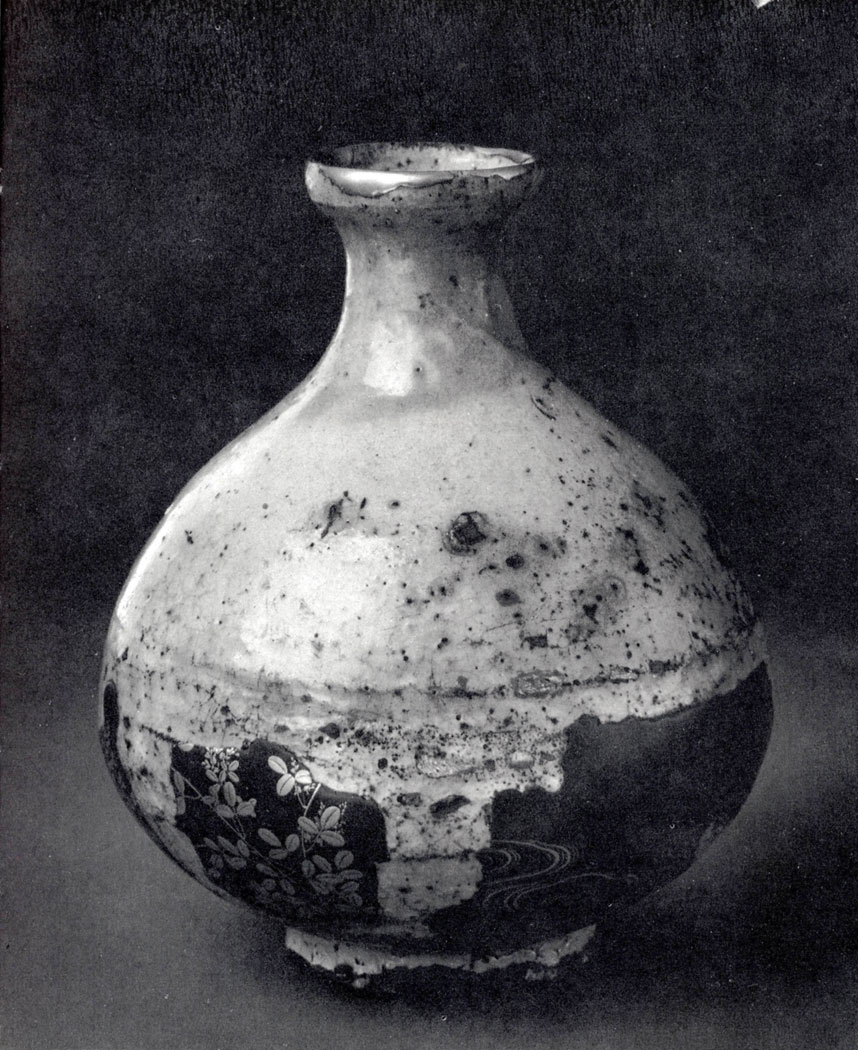

Flower vase

Shino pottery, Japan. 17th century

Clay, glazed, with fragments of lacquer paintings.

Height 15 cm, diameter 12.5 cm. Inv. No. 15301 I

Received in 1967 from the History Museum, Moscow.

This flower vase is treated in a manner characteristic of the Shino pottery where many Korean craftsmen used to work. It has a clear-cut elegant shape and elaborate decoration. In the lower part of the body, the greyish-white glaze is contrasted with fragments of brown lacquer covered with delicate gold-painted floral ornamentation. This unexpected combination produces a striking visual effect.

Bowl

By Sakaida Kakiemon (1596-1666). Japan

Porcelain.

Height 11.5 cm, diameter 24 cm. lnv. No. 6378 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow.

Porcelain-making, whose secrets were imported from China, has existed in Japan since the 16th century. Among the most popular wares were those produced at Sarayama near Arita, on Kyushu. Porcelain-making was established there in 1617 by a Korean potter Ri Sampei who had discovered deposits of kaolin close to the city precincts. The Arita porcelain was distinguished by an exquisite combination of underglaze painting in cobalt blue with overglaze painting in red and gold. Kakiemon was a name bestowed on a potter called Sakaida who introduced some novel methods of porcelain decoration. He borrowed the Chinese technique of making enamels and evolved his own type of decoration based on a certain colour scheme which he named "uwatsuke". Sakaida Kakiemon used the advantage of the white china for translucent glazes and brilliant saturated colours, among which red was prevalent. The painted design which he eventually elaborated included flowers, birds and butterflies. It was known among his followers under his own name-"kakiemon", which, incidentally, comes from kaki, "a ripe plum", whose purple colour was associated with the hues used in overglaze painting. The minute "creeping" pattern usually decorates the central part of the article.

The bowl reproduced here is a vivid example of the artist's style. The technique introduced by Sakaida Kakiemon is still used by many Japanese potters. Japanese porcelain was in great demand in Europe and, in fact, at one time influenced Delft, Meissen and Worcester porcelain wares.

Vase

Satsuma pottery, Japan. Early 18th century

Faience.

Height 27 cm, diameter 16.2 cm. lnv. No. 315 I

Received in 1919 from the Art and Industry School (formerly the Stroganov Art School), Moscow.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, due to the appearance and growth of new cities and in response to the tastes of the newly emerged urban classes, Japanese ceramics were gradually losing their original austerity and simplicity of shape and decor. Elaborate ornamentation in brilliant colours was coming into vogue. Beginning with the 18th century large quantities of porcelain ware were made specifically for exporting to Europe, which also affected the artistic style within the craft as a whole. A characteristic example is the ware from the potteries of Satsuma province. Pottery-making began there in the 16th century when Prince Toyotomi Hideyoshi had brought back to Japan from his military expedition to Korean peninsula some 500 potters' families and settled them on the Isle of Kushu. In the early 17th century, soft clay of a kind suitable for faience-making was discovered in the province. It gave rise to the manufacturing of thin, almost white earthenware evenly coated with white glaze with a delicate golden tinge. At the end of the 18th century several Satsuma potters made a tour of different potteries in other parts of the country. The outcome of the tour was the emergence of faience of a harder texture with large-scale ornamentation in brilliant glazes against a pale background. The vase reproduced here is a case in point. Large red and blue chrysanthemums stand out boldly on the background of cream-coloured glaze. The painted decor and the background are in perfect balance with each other, and the former is arranged in such a way as to present a complete decorative scheme from whatever angle the vase is viewed. The upper part of the vase, free of any decoration as it is, sets off the painted design to the best advantage, contributing to the overall visual effect.

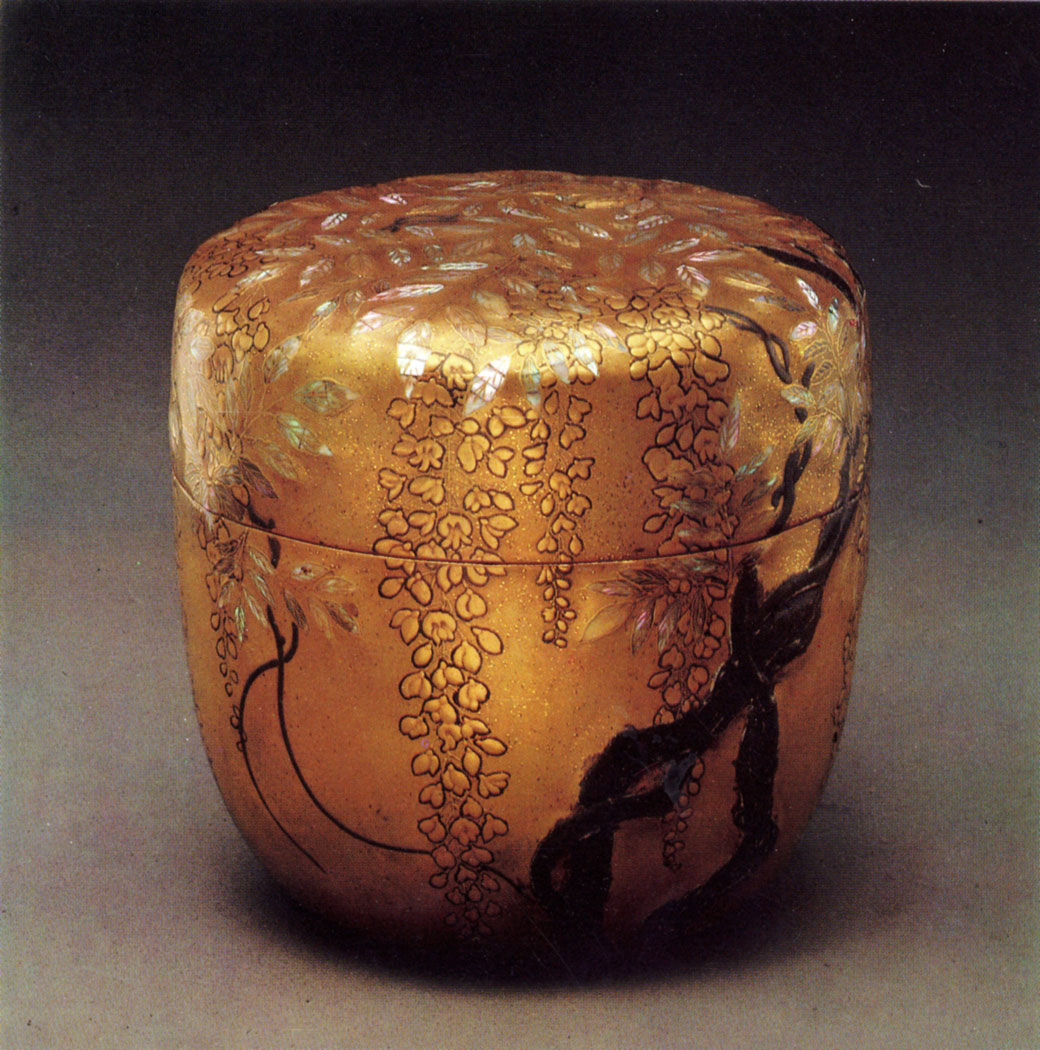

Tea caddy

By Ogata Korin (?) (1658-1716). Japan

Gold-flake lacquer, with mother-of-pearl decoration.

Height 9.2 cm, diameter 9 cm. lnv. No. 345 I

Received in 1919 from the Art and Industry School (formerly the Stroganov Art School), Moscow.

The making of lacquer articles is one of the Japanese traditional crafts. Lacquer wares were treated in Japan as luxury articles to be treasured among the family's most valuable possessions, and they were passed down from generation to generation. In the late 17th and early 18th century, among the several centres of lacquer-making which existed in Japan, the most important were the workshops of Kyoto.

This tea caddy is attributed to Ogata Korin, a representative of the Kyoto school and a universally gifted artist who distinguished himself as a painter, a potter, a maker of lacquers and a designer of fans and kimonos. He invented a transparent varnish made of sugar maple sap and was the first to use tin, lead and mother-of-pearl in the ornamentation of lacquer articles. His unique sense of decorativeness enabled the artist to convey his attitude towards nature through the decoration of his lacquers. His flower petals, supple grass stems and tree branches look like jewels scattered over the shimmering surface of the articles. The realistic and the imaginary in his designs are almost inseparable.

The tea caddy reproduced is a fine example of Ogata Korin's artistic ingenuity which created this picturesque contrast between the shimmering blue-greenish mother-of-pearl of the wistaria-flower and the boldly shining gold of the background.

Netsukes

Japan

Kirin (mythological creature). By Tomotada Yanagawa. 18th century

Carved wood.

Height 10.4 cm. Inv. No. 1755 I

Received in 1923 from the First Proletarian Museum, Moscow.

Actor. By Gyokumin. 19th century

Carved ivory.

Height 7 cm. Inv. No. 5692 I

Received in 1945 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow.

Netsuke is the Japanese form of a toggle. It is used to secure the cord of a tobacco pouch or an inro (small receptacle for medicine) to the belt. Netsuke were made from a large variety of materials-wood, ivory or, less frequently, stone, horn, tortoiseshell and porcelain. The term "netsuke" was first mentioned in the 17th-century chronicles. The formation and subsequent evolution of miniature sculputure took a little more than three hundred years. Netsukes came into usage with the spread of tobacco smoking and the vogue for wearing inros. From the mid-18th century onwards the functional aspect of netsukes subsided, and they came to be considered as objets d'art in their own right. The carvers drew their motifs from the everyday life of the common man, from legends, myths and also from the natural world. Many extant netsukes are signed by well-known professional sculptors.

One of these was Tomotada Yanagawa. He was born in Kyoto in the 1780s. His netsukes represented actors, peasants and animals, the latter being his strongest point. The netsuke reproduced here shows Kirin-a good genius, a creature with the head of a dragon, the body of a chamois and the mane of a lion. The scales covering its neck are marked with deep vigorous lines, and the combination of the incised and smooth ivory surface creates a decorative effect.

The netsuke by Gyokumin represents an actor performing the sambasho dance. He is dressed in a kimono decorated with patterns consisting of pine twigs and cranes-symbols of longevity. According to a Japanese legend, in 801 citizens of Nara tried to stop the eruption of a volcano with the sambasho dance. Nowadays the sambasho is the introductory dance of the Kabuki performances.

Frogs

By Masanao Suzuki. Japan. Early 19th century

Carved wood.

Height 4 cm. Inv. No. 1953 I

Received in 1926 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow.

The relatively rapid development of the netsuke as a branch of sculpture relied on the thousand-year history during which the rich experience and superb artistic skills had been accumulated. The absence of any restrictive canons, the harmony of form and the subject matter, the apt choice of the material, the originality of motifs and, finally, the emotional touch are the distinctive features of the Japanese netsuke.

This netsuke representing two frogs sitting on a bucket is based on an old Japanese parable. It tells of frogs who were afraid of the bucket, for, being dropped into the well, it made a loud splashing noise. Once the bucket was left behind, by the well. The frogs leaped onto it and saw that there was nothing in it to be afraid of. Thus in life, so the moral goes, one should take a close look at that which gives him fear, and fear will be gone. Masanao was renowned for his ability to reveal the beauty of wood, to accentuate its warm colour and its natural texture. His nefsukes are remarkable for theiraccuracy of detail and the well-balanced composition.

Lotus-flower

By Tomioka Tessai (1836-1924). An album sheet. Japan

Indian ink and mineral pigments.

52 × 60 cm. lnv. No. 14910 I

Received in 1966 from the Kremlin Armoury, Moscow. First publication.

Tomioka Hyakuren (known as Tessai) was born in Kyoto. As a young man, he was a student of Japanese and Chinese classical literature. At nineteen he entered a Buddhist monastery where he received an education in philosophy and art. His subsequent activity embraced philosophy, history, painting, calligraphy and restoration.

As a painter, he followed the tradition of the bunjinga school. Due to his vast artistic activity this trend is still living in contemporary Japanese painting. Tessai was a keen observer of natural phenomena; he travelled all over his country and for a long time lived in the mountains. He sought a harmonious union of man and nature, whose laws he strove to comprehend. His contemplation of nature gave him joy and peace of mind. Throughout his long life Tomioka painted pictures representing either idealized imaginary scenes or a series of topographical views. In his last years the artist was especially fond of painting flowers. His flowers and birds pieces display a somewhat impulsive and expressive linear treatment, with many changes of tone and contrasts between Indian ink outlines and flashes of saturated colour. The pictures are supplied with explanatory notes executed in conventional calligraphic manner.

Poems and Cliffs

By Hiratsuka Un'ichi (born 1895). Japan

Hand-coloured woodblock print.

47.8 × 39 cm. Inv. No. 27137

Acquired in 1975 from the A. Kolomiets collection.

20th-century Japanese engravers of the older generation-Oda Kazumaro (1882-1956), Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955) and Hiratsuka Un'ichi-did very much by way of reviving and promoting the traditional Japanese art of printing. They initiated a number of societies and associations of print-makers. In his work Hiratsuka managed to achieve a natural and effective combination of Western European artistic principles and the traditional techniques of Japanese printing. His legacy amounts to over 500 prints and, besides, a number of books on the technique of print-making. A distinctive and novel feature of his prints was the contrast of black and white, a combination which, within the classical Japanese tradition, was found only at the initial stage of the print-maker's work. "I believe black and white to be the most beautiful colours," the artist once wrote, "to use musical terms, black and white create rhythm and harmony." Among Hiratsuka's favourite subjects were the sights of Kyoto and peaceful countryside scenes. He was remarkably good at conveying a mood of tranquillity and calm, and this ability won him the title of the Master of Silence. His xylograph Poems and Cliffs is permeated with just such a peaceful mood, and its charm lies in the artist's poetic sentiment and sense of beauty. Another characteristic quality of Hiratsuka's work is its inner link with many aspects of national culture: suiboku paintings, old Buddhist prints, popular paper-cuttings, etc. They all share a tendency towards monochrome colouring, laconic pictorial devices and graphic expressiveness. Following his predecessors, Hiratsuka combined pictorial representations with calligraphic inscriptions- short tanka poems.

Kwannon

By Munakata Shiko (1905-1975). Japan

Hand-coloured woodblock print.

19.5 × 24.5 cm. Inv. No. 27044

Acquired in 1975 from the A. Kolomiets collection.

Munakata Shiko is one of the most popular Japanese graphic artists. The aesthetic foundations of his works were based on Japanese mythology and Buddhist philosophy. He also incorporated elements of classical monochrome painting, early Buddhist prints and various forms of folk art in his prints. "True art," he wrote, "should be pure and immune to external influences. I want my works to be nothing but Japanese." Yet Munakata's prints exhibit a quality uncommon for traditional Japanese art-a certain bewilderment and inner anxiety; their jerky rhythms of broken lines and seemingly desultory patches of colour appear to symbolize the life of modern Japan. His works always suggest a range of interpretations and are invariably based on a complex conception. Buddhist divinities, for instance, appear in his prints as personifications of abstract notions and moral categories. In this print, Kwannon, Munakata dwells on a traditional image of the goddess of mercy, but treats his subject from the modern standpoint. Munakata was an artist of rich and varied talent. His prints combine ornamental motifs, calligraphy, rhythmically arranged patches of colour, lines and hatched areas. He tinted his prints by hand, applying the colours in diffused shapeless stains and washes which created an illusion of scintillating blue, pink, yellow and pale violet. Delicate washes set off by bold and vigorous lines create a wonderful decorative quality which betray the affinity of his works with folk art.

Mountain Lake

By Kitaoka Fumio (born 1918). Japan. 1970

Hand-coloured woodblock print.

39 × 54 cm. Inv. No. 27058 I

Received in 1971 (bought at the artist's one-man show in Moscow). First publication.

Kitaoka Fumio was born in Tokyo. In 1941, he graduated from the Tokyo Art College. His first teacher was Hiratsuka Un'ichi. Later Kitaoka went to France and studied the technique of engraving on end-grain wood there. From 1945 to 1947 the artist was engaged in producing a series of black-and-white prints in a strict realistic manner. The grim and highly dramatic images of that cycle were inspired by the calamities of the war and by the hardships of post-war life.

The 1950s saw an abrupt change in the artist's subject matter and style. Kitaoka relinquished his former repertory of social themes and turned to landscape and still life. His manner became purely decorative. At present Kitaoka Fumio is one of the most eminent figures in Japanese graphic art. His works are characterized by a pale palette, including complicated hues, and by thin flowing lines. The Museum possesses several prints by the artist, Mountain Lake being one of them. Even the most common colours seem to have acquired a new, radiant quality in this work. The intricate combination of blue and green with white strokes, the flat treatment of space and the decoratively stylized forms create a singularly beautiful picture of Japanese scenery.

A Village

By Minakawa Taizo (born 1917).

Two-panel screen. Japan. 1950s

Cotton fabric (negative dyeing method).

Height 176 cm (each panel is 91.6 cm wide). Inv. No. 12440 I

Received in 1957 (bought in Tokyo by the USSR Ministry of Culture).

Traditional Japanese painting on screens is a peculiar combination of fine and applied arts which is still popular with many artists. Nearly all of them employ the well-established negative dyeing method, in which the fabric is stretched on a special frame and the design applied to it is covered with wax or rice glue before the fabric is dipped, so that the waxed portions do not take the dye. Then the fabric is dried and the wax scratched off. The process is repeated many times until all intended colours of the design are there.

The conventional rural landscape on this screen is drawn with thick lines. The artist worked in a characteristically graphic manner and employed a fairly limited range of colour. His creative work reveals a close link with the traditions of national art, particularly with early Buddhist prints and the popular craft of cloth-printing. Their influence is apparent in the artist's predilection for linear treatment, in the flatness of his representations, in the decoratively stylized and simplified forms and, finally, in the rhythmical reiteration of certain parts of the composition.

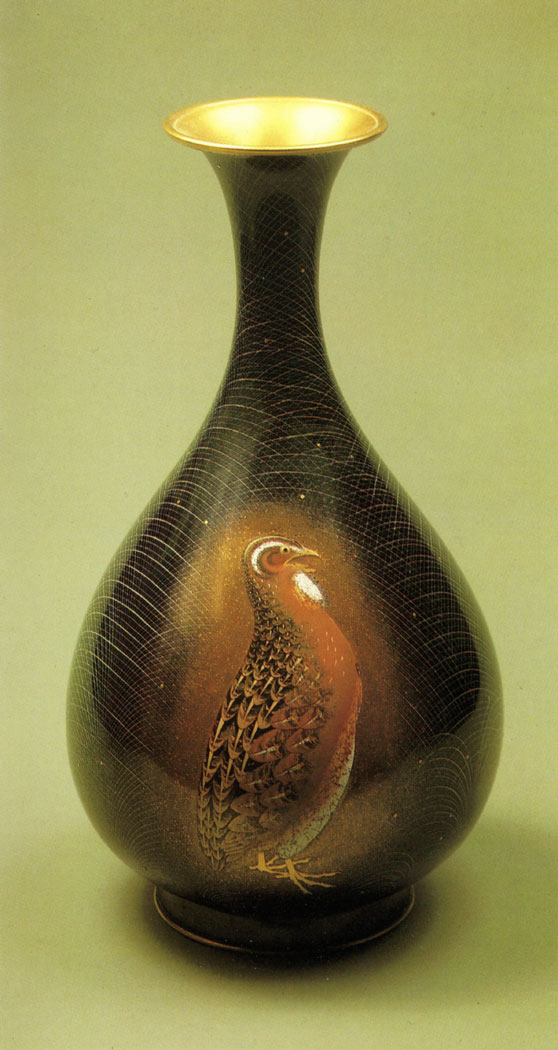

Vase with a partridge

By Matsuda Gonroku (born 1896). Japan. 1950s

Metal, with gold lacquer decoration (maki-e).

Height 30.1 cm, diameter 16.5cm. Inv. No. 12654 I

Received in 1957 (bought in Tokyo by the USSR Ministry of Culture).

Matsuda Gonroku, a well-known Japanese artist and member of the Japanese Art Academy, was born in Kanazawa, in the prefecture of Ishikawa, and spent most of his creative career in Tokyo. In his artistic work Matsuda Gonroku was a faithful follower of national traditions, and skilfully combined various methods of painting, including the rare and painstaking gold lacquer technique. The primary material used by Matsuda Gonroku for making the objects themselves was metal. The metal surface of the article was covered with alternating layers of lacquer and gold powder. After a thorough polishing the lacquered surface acquired a soft golden sheen. Afterwards, with the help of various subtle shades of lacquer, the artist created elaborate decorative compositions which exhibit his fine sensitivity towards nature.

Kimono: Torrent

By Nakamura Katsuma (born 1894). Japan. 1950s

Silk, with embroidery (negative dyeing method), hand-colouring.

168 × 121 cm. Inv. No. 12507 I

Received in 1957 (bought in Tokyo by the USSR Ministry of Culture).

The kimono, the traditional Japanese costume, has existed since the 15th century to this day without any major changes in its basic design. It is a loosely cut straight gown with long sleeves of the shode type. The most popular kind of kimono is the koshode (for everyday wear). Made of silk or cotton and worn by men, women and children alike, kimonos differ in their decor, their sashes and other accessories. The most expensive part of a women's kimono is obi-a wide ornate sash, often of brocade, which was tied in a "butterfly" or "drum" bow at the back. On festive occasions Japanese women wear kimonos of the furisode type, with long hanging sleeves (up to a meter and a half wide). The cloth for the furisode kimonos was woven, embroidered and painted by hand. Seasonal flowers and symbols of goodwill are among the most usual motifs. The representational style of ornamentation in kimono-making emerged in the 17th century. The kimono decorated in this style was viewed as a kind of ornamental panel or a picture, and was admired as such. It was unfolded and smoothed out to provide a better view of the decor, or else hung on a special hanger as a decorative panel.

One of the finest contemporary examples in the Museum is the koshode decorated and signed by

Nakamura Katsuma. It is hand-painted, embroidered and embellished with brocade applique. Kimonos were usually decorated by celebrated Japanese artists. As the convention dictates, the decor is arranged on the back. The white torrent of a mountain spring carrying yellow autumn leaves outlined with wide contours runs downwards from the shoulder to the hem. The design stands out boldly against the black silk background. The composition is conceived in full accordance with the character of the garment with its loose flowing folds.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'