China

Cup of the ku type

China. 2nd millennium BC

Bronze, cast and engraved.

Height 29.5 cm. lnv. No. 6190 l

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow. First publication.

The ancient Chinese bronze vessels of the Shang-Yin dynasty (17th to 12th centuries BC) were unearthed during the excavations at the sites of Anyang and Chengchou where the remains of forges and potters' workshops had been found. Bronze articles were made by the complicated method of casting. The moulds discovered at the sites suggest the following process. First, the vessel is modelled in fine clay, with the main outline of the decoration on its surface. Second, clay is pressed onto the surface of the model to make a mould, which is then detached in section from the model and the design touched up and elaborated by hand incising or, later, carving. Third, the sections of the mould are fitted with mortises and tenons for reassembly, and the model, which will form the inner core, is shaved down to create a space between it and the outer mould corresponding to the desired thickness of the vessel walls. Small spacers would hold model and mould apart during casting. Fourth, the assembly of mould pieces and core is dried and fired to form the completed piece-mould, and one or more venting holes are made on each side of the mould. Fifth, molten bronze is poured through a hole on top of the assembly into the allocated space. Finally, the assembly is removed after cooling, and the vessel filed and polished.

Another method consists in filling the space between two clay layers with wax which melts when molten bronze is poured in.

These bronze vessels were designed for ritual purposes. For example the ku cup was used for pouring out wine during the religious ceremonies. Its shape is quite simple and functional, but at the same time artistically faultless. The cup widens in a funnel-like fashion towards the rim and at the base. Its body is encircled with a relief band which makes it more convenient for the hand to hold. The surface of the cup is decorated with the leiwen pattern (the motif of thunder) in the form of engraved spirals symbolizing the sky.

Vessel of the kuei type

China. 5th-3rd centuries BC

Carved jade.

Height 9.3 cm, diameter 18.2 cm. lnv. No. 2749l

Received in 1924 from the History Museum, Moscow.

Ritual objects made of jade (yu, in Chinese) became common in China from the 5th century BC onwards. The ancient Chinese treated jade as a magic stone with healing properties. Jade and jasper articles held a special place in the treasury of the emperors of China, and the absence of these articles was treated as a sign of penury.

The vessel of a semispheric shape with two sculptured handles is adorned with a relief tao-tieh mask. Its symbolic meaning is obscure: there is a hypothesis, that originally such masks had represented demons in human aspect, but subsequent modifications endowed them with a zoomorphic character symbolizing totems from the animal world. The delicate modelling of forms, the smoothly polished surface and the natural beauty of light-grey stone with yellowish and brownish stains account for the exquisite charm of the article.

Mirror

China. 2nd century BC-1 st century AD

Cast bronze.

Diameter 15 cm. Inv. No. 26851 I

Bequeathed to the Museum in 1975 by Kalabushkin and Guryan. First publication.

According to the earliest written records, bronze mirrors first appeared in China as early as the 8th century BC. They had both a religious and a domestic use.

The smooth surface of the front side was achieved by means of polishing it with mercury; the reverse side was decorated with ornamentation. Such round-shaped mirrors with a loop for passing a cord through it were most common during the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD).

The ornamentation of the Han mirrors was varied but each of its varieties was in one way or another always connected with the cosmogonic beliefs of the ancient Chinese. One of the simplest versions is represented by this mirror. The cosmic symbolism here finds expression in the twelve convex circles in the centre which stand for the planets. The eight pointed projections around them symbolize the seasons of the year and also the eight pillars supporting the sky and regulating the orbits of the heavenly bodies. The relief rope-pattern band running along the border was referred to in the Chinese tradition as "rays of light".

Mirrors from the Han period, beginning with the mid-2nd century AD, sometimes also bear hieroglyphic inscriptions. Their content is confined to wishes of well-being. The mirror reproduced here has such an inscription, in which every hieroglyph is inscribed within a square. Such a method of writing accounted for a regular and rhythmic arrangement of the hieroglyphs along the border, thus making the inscription an integral part of the ornamental design.

Figurine of an official

China. 5th or 6th century

Clay.

Height 23.5 cm. Inv. No. 15350 I

Received in 1967 from the History Museum, Moscow. First publication.

This figurine of a Chinese official was made during the Wei kingdom (386-534) when after a long period of feudal strife the northern part of the country became a powerful state. It was a time of the growing influence of Buddhism and the establishment of new Buddhist iconography.

Wei sculpture was characterized by a unique spirituality of images, an expressive treatment of volumes and delicately modelled folds. The sculptor succeeded in rendering the character of a concrete person-reserved, sullen and taciturn, but not devoid of certain spiritual qualities. The proportions of the figure are elongated, the inclined head seems large compared with the body, and the stylized folds of the garments are rendered in smooth flowing lines.

Bodhisattva Kuan-Yin

China. 11th century

Bronze, cast and chased.

Height 67 cm. lnv. No. 29944 КП

First publication.

The figure of Bodhisattva Kuan-Yin (the Buddhist goddess of mercy) is a splendid example of Chinese plastic arts of the Sung dynasty (960-1279)-the time of its flourishing. Chinese Buddhist sculpture of that period is characterized by a broad stylistic variety, complicated iconography, close attention to the symbolism of gestures and a marked emphasis on various details and conventional accessories.

The cast-bronze statue of Kuan-Yin is placed on a high base in the shape of a lotus-flower. In accordance with the Buddhist canon, her head is crowned with another ten smaller heads (as the legend goes, the goddess could not contain her grief over the sufferings of the people and her head broke into several parts; Buddha collected the fragments and assembled eleven heads out of them). The triangular medallion over the goddess's forehead is decorated with a relief representation of Amida Buddha. In her slightly raised left hand the goddess holds the traditional little jug, kalasha, and in her right hand-a rosary. Her garment flows down from her shoulders in a cascade of stylized folds, echoed by the long necklaces hanging down from her neck. The forms are characterized by an elaborate rhythm. The treatment of the statue is largely decorative in character, this decorativeness being probably inspired by painting, which at the time of the Sung dynasty assumed the leading role among the arts.

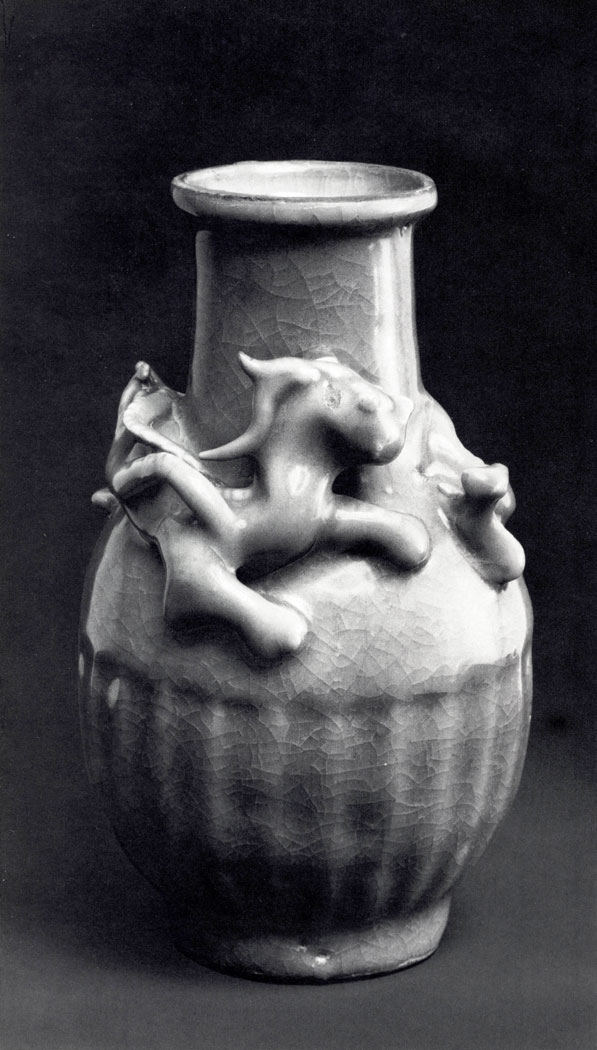

Vase

China. 10th-13th centuries

Clay.

Height 23 cm, diameter 11 cm. lnv. No. 6303l

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow.

Ceramic crafts in China reached a very high level at the time of the Sung dynasty (960-1279). Numerous potteries were scattered all over the country. The largest of them became world-famous, as for example, Lung-ch'uan (Chechien province) and Chun (Honan province). The blue and greenish-grey celadon glazes which cover the wares from those workshops imitated the natural colours of jade, which was highly valued in China. These celadon glazes were derived from iron; they were usually applied before firing in the form of a ferruginous wash. Celadons were sometimes decorated with crackles, relief ornamentation and hand-modelled elements. Chinese celadons were widely famous outside China and were exported to Iran, South-East Asia and to the east coast of Africa.

The vase reproduced here is reminiscent of an amphora in shape. The upper part of its body is decorated with applied hand-modelled dragons and its lower part is grooved. The thick greenish-grey crackled glaze endows it with a particularly noble look.

Saucer

China. 10th-13th centuries

Clay.

Diameter 17.5cm. Inv. No. 14508 I

Received in 1963 from Sergei Kiseliov's archaeological expedition at Karakorum, Mongolia.

Rich and expressive painted decor is a distinctive feature of pottery from Tz'uchou (Hopei province). A mild-coloured, usually unglazed article was covered by the Tz'uchou potters with monochrome or two-coloured floral design. Such is the saucer reproduced here with its green-and-red flowers painted in the unrestrained manner.

Cup

China. 10th-13th centuries

Glazed porcelain.

Height 6 cm, diameter 13.5 cm. Inv. No. 8073 I

Donated in 1949 by Dmitry Melnikov.

The first porcelain was produced in China somewhere about the 3rd century AD. Its thinness and resonant quality were achieved through the addition of feldspar and quartz. Snow-white transclucent porcelain items covered with thin transparent glazes were produced at Tingchou (Hopei province) almost exclusively for the emperor's palace. Bowls, vases and incense-burners were adorned with fine carved ornamentation called hsuhua (satin-stitch embroidery).

The wine-cup reproduced here is in the form of a lotus-flower with petals slightly thickened towards the edges. The beauty of its snow-white surface is emphasized by the specks of light playing on the relief of the ornamentation.

Portrait of the Poetess Su Jolan

By Kuan Taosheng (1264- 1319). China. 1311

Indian ink and slight colour on silk.

205 × 21 cm. lnv. No. 2325 l

Received in 1926 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow.

Kuan Taosheng was born in the province of Chechien. She was married to the famous artist Chao Mengfu (1254-1322). She specialized in painting and calligraphy following the then popular Fukup'ai (classical revival) style. The portrait of the poetess Su Jolan belongs to the few extant works by Kuan Taosheng. The round face, tightly pressed lips and highly raised eyebrows of the model are drawn in thin and delicate lines. The old-fashioned coiffure represents Fenghuang, a fantastic bird. A frail and slender body is discernible under the loose and heavy folds of the garment. In her hands the poetess has a scroll with poems. The delicate brush seems to have barely touched the silk while creating this image of a sublime and beautiful creature. The portrait of the poetess is accompanied with her palindrome-a poem which reads the same forwards and backwards. This palindrome is a love message from Su Jolan to her husband who is away from home. At the bottom of the scroll there are several lines by the artist herself: "In the year of Hsinhai (1311) my husband went to Ts'anwu on business. While sitting at leisure in my study I chanced to find in my bookcase a palindrome written by Jolan. Beautiful feelings and rare acumen. I was reading the poem without feeling any weariness. Having then felt an urge to respond to it, I took some silk and wrote the palindrome on it. Tienhou. Written by Kuan Taosheng".

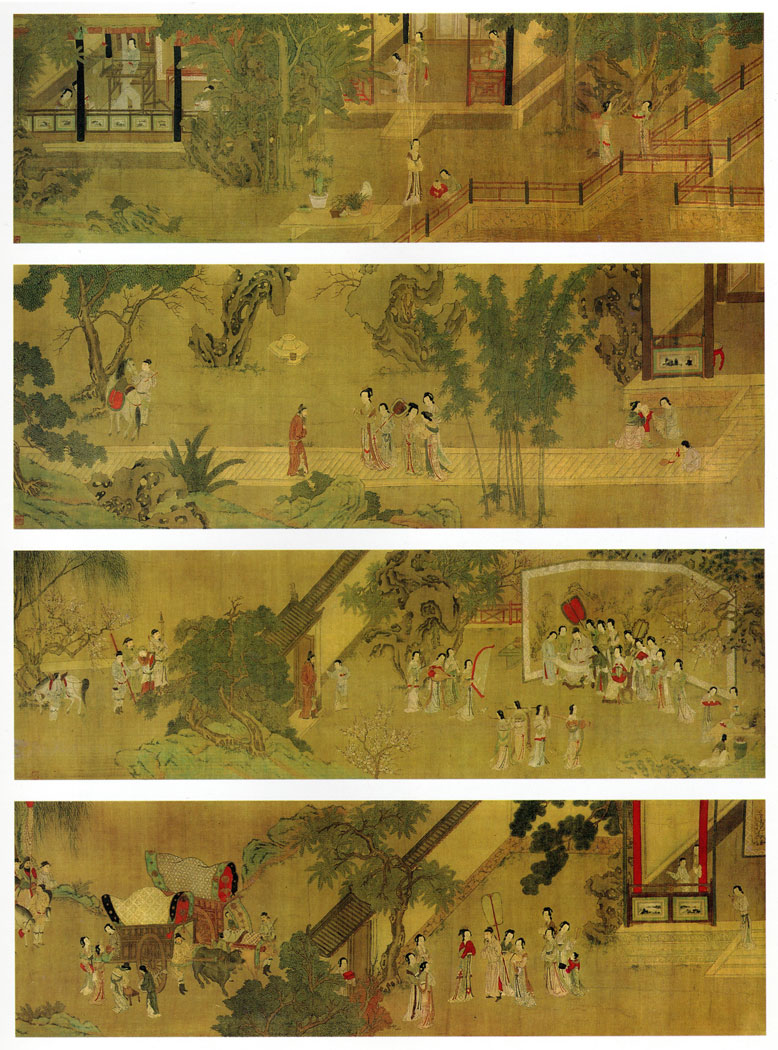

A Poem about an Abandoned Wife

By Ch'ou Ying (active between 1500 and 1570). China

Indian ink and slight colour on silk.

30.9 × 102 cm; 30.9 × 87 cm; 30.9 × 98.4 cm; 30.9 × 114cm. lnv. Nos. 2320 I; 2321 I; 2323 I; 2324 I

Received in 1923 from the State Museum Reserve, Moscow.

Ch'ou Ying was born in T'aits'ang. He lived and worked in the south of China, in the town of Suchou. His teachers were the painters Chouch'en and T'ang Yin. The pictures which brought him fame were painted in the traditional kungpi (meticulous brush) style, which implied a deliberate and reserved style of painting with particular attention to minute details. Ch'ou Ying represented a new, narrative trend in Chinese painting (jenwu) closely connected with classical literature.

This scroll is based on the famous story about the poetess Su Jolan. The inscription performed by the celebrated calligrapher Wen Chengming gives a brief outline of the plot of the poem. A young woman is abandoned by her husband. He left for a remote province and forgot about her there. Longing for her husband's return, the young woman composes a poem of her faithful love for him. The first part of the scroll shows her as she is embroidering her poem on a piece of brocade. The second part shows her sending a messenger to her husband with the scroll. In the third part the husband is deeply moved by his wife's poem, and in the fourth, he is seen leaving his mistress, in spite of her entreaties, to return home to his wife the poetess. The artist treats the story with a subtle lyricism. The attitudes and gestures of the characters, the folds of their garments play an important part in their portrayal. The poetess herself is shown as a gracious woman with light movements and a supple figure. The artist's manner is remarkable for the elegance of linear treatment and for a simple arrangement in which there is nothing excessive or redundant. The architectural background with its straight lines standing out in dark red endows the scenes with a clarity of composition and serves as a vehicle for a unified rhythm which brings together the four isolated episodes.

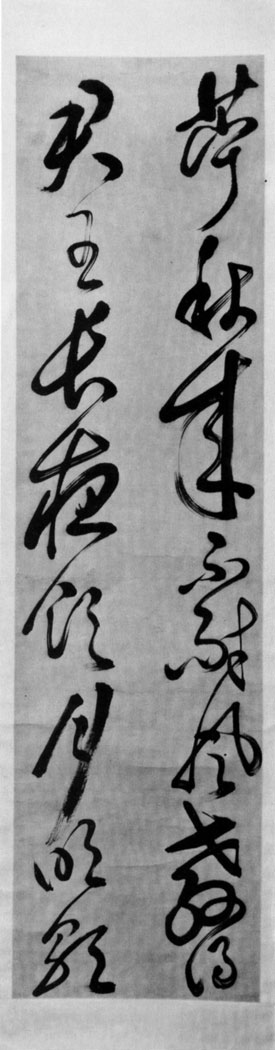

Meditation on the Seasons of the Year

By Chu Yiinmin. Fragment of a polyptych. China. Late 15th or early 16th century

Indian ink on paper.

183 × 51 cm. Inv. No. 24326 I

Acquired in 1971 from a private collection. First publication.

In medieval China calligraphy was an independent and highly respected genre of art whose study formed part of classical education. Like painting, calligraphy as an art was split into numerous schools and characterized by various styles. Paper, a soft brush, an inkpot and ink have since the 3rd century BC, the time of the Han dynasty, been the indispensable possessions of every educated Chinese person. The Chinese believed that calligraphy, like music, could convey the mood and express the feelings of the scribe. The force and specific alternations of the strokes and the intensity of script afford an opportunity to form an opinion of the calligrapher's personality.

Chu Yunmin was an outstanding master of calligraphy of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Little is known about his life. The exact dates of his birth and death remain a mystery. But it is known that he held a number of high official positions and was a poet. His instrument was a big long brush, and he worked in the huashih (unbroken stroke) manner. The polyptych, a part of which is reproduced here, is attributed to Chu Yunmin. Originally it consisted of twelve scrolls, eight of which are now part of the Museum's collection. Chu Yunmin's calligraphy was valued for the expressive intensity of line, well-balanced combinations of graphic elements and a skilful juxtaposition of saturated black strokes with very delicate touches of the dry brush.

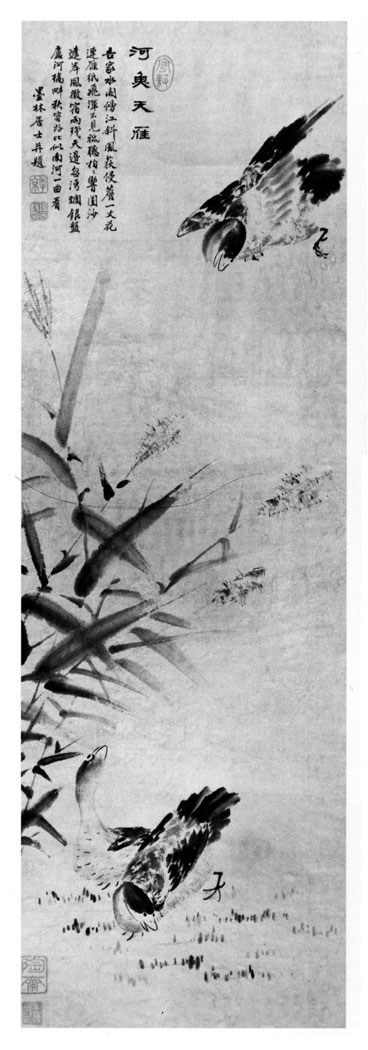

Geese

By Hsiang Yuanpien (1525-1590). China. 1587

Indian ink on paper.

26.5 × 81.7 cm. Inv. No. 13695 I

Acquired in 1961 from a private collection. First publication.

Hsiang Yuanpien (alias Molin Tseishih) was born in the town of Chiahsing (Chechien province). He was a renowned collector and connoisseur of painting. His own works which brought him fame were monochrome landscapes and pictures of "the four nobles"-the pine, bamboo, orchid and plum-tree. The scroll reproduced here represents a riverside scene with two geese in the sedge thicket on the bank and a third in the air. The contours of all the elements in the picture seem to be barely indicated with delicate touches of Indian ink. The light-coloured ink is supplemented with occasional lines of deep black. The artist employed the so-called "dry" method of painting which implied a very limited use of water for dissolving the ink.

Sometimes he combined it with the "wet" method in the hsia hsei manner, conveying an effect of space, air and the coolness of the river. The inscription in the top left corner reads: "There are fish in the river and geese in the sky." The picture is accompanied by a poem:

Our house stood on the river. Wild geese are flying over the house, but they are not to be seen. Only the rustling of the sand is heard. A light wind is blowing from the far bank Bringing the moisture of the rain that has passed. The silver bowl of the moon appears suddenly, floating over the skyline. How beautiful is an autumn view by the bridge over the river Lu. At first sight it is just like the river Nan Ho. Composed and painted by Molin Tseishih.

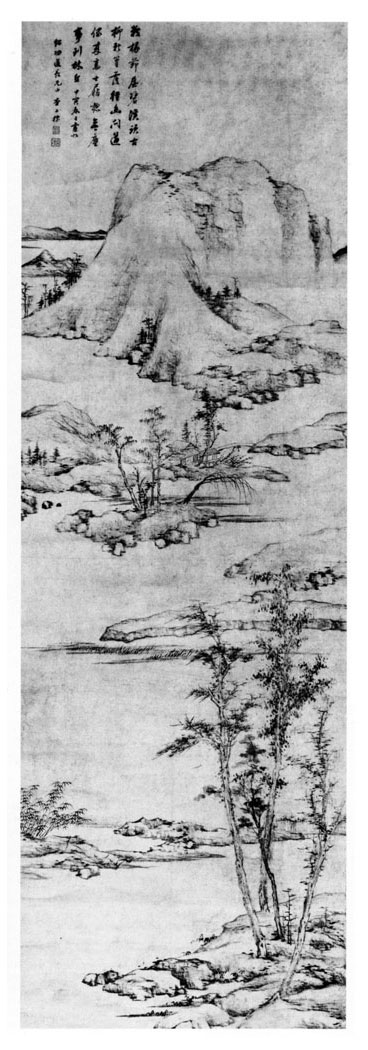

Landscape

By Ch'a Shihpiao (1615-1698). China. 1674

Indian ink and slight colour on paper.

141 × 46cm. lnv. No. 6518 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow.

This landscape by Ch'a Shihpiao was inspired by works of the famous Yuan landscape painter Ni Tsan (1301-1374). Following the tradition, the artist adhered to the basic principles of old landscape painting: "diffused" perspective, a succession of picture planes, the use of various shades of black Indian ink in the air treatment, etc. In the modelling of the forms an immense significance was attached to the line. The artist painted in the so-called "dry" method. Holding the brush at an angle, with delicate strokes, lines and transparent washes, he depicted the trees, mountains, stones and water. Ch'a Shihpiao's landscape is uninhabited by people or animals, and is serene and somewhat melancholic. The picture is accompanied by a poem:

The humble huts by the head of an emerald stream. A path runs along in the distance concealed by venerable willows and young bamboos. You came along the country road wearing a noble dignitary's shoes. But no longer have you any vain thoughts in your mind, And you are absorbed in the woods and hills around you. On a spring day of the year of Chiayin (1674). By Ch'a Shihpiao.

Poppies

By Yun Shoup'ing (1633-1699). An album sheet. China

Indian ink and mineral pigments on silk.

26.2 × 31.5cm. lnv. No. 1556l

Received in 1936 from the Museum of Ethnology, Moscow.

The huaniao (flowers and birds) genre appeared in Chinese painting during the Tang dynasty (618-907). It was modified during the subsequent centuries, always remaining one of the most popular genres in Chinese art. Inspired by the natural harmony and beauty of flowers, by the variety of their colours and shapes, the artists endowed them with poetic and symbolic properties, associating them with cosmogonic beliefs and tokens of goodwill. One of the most celebrated representatives of this genre, Yun Shoup'ing was born in the province of Chiangsu. He was a man of many talents and distin-guished himself as a poet, an artist and a callig-rapher. As an artist, he worked in the so-called boneless (contourless) manner of painting: his pictorial skill relied on the use of traslucent colours, on light brushstrokes and on the harmony of patches of colour. The brilliantly coloured poppies dancing in the soft spring breeze personify the legendary image of Yu, a charming and gracious dancer. The calligraphic inscription adds another expressive touch to the composition and explains its meaning: "The beauty dropped her eyes and, lighting the incense-burner, sank languorously onto the seat. The heavy pearl ornaments shaped like the bird Fenghuang weigh upon the headpiece made of halcyon feathers. In the southern part of the province of Chiangsu the flowers of spring are called Yu, so beautiful and delicate they are. When the poppies are stirred by a breath of wind, they are not easy to paint. Written by Nant'ien Shoup'ing."

Portrait of the Buddhist Patriarch Ch'ang Mei laotsu

By anonymous artist. China. 16th century

Slight colour on silk.

112 × 70 cm. lnv.No.2492 I

Received in 1928 from the Museum of Modern Western Painting, Moscow.

According to written records, portrait painting developed in China in the 5th century BC, with funerary portraiture associated with the Chinese cult of ancestors at the forefront. A funerary portrait was usually painted after the person's death. The people entitled to such posthumous honours were government officials, dignitaries and members of their families, as well as high-ranking Buddhist priests. The portraits were executed in a formal manner and usually possessed a somewhat didactic quality. The convention dictated that an effigy of an ancestor should command the respect of "the reverential sons and loving grandsons". The canons of portrait painting faithfully followed by Chinese artists had been fully elaborated by the 16th century. The primary task of the portraitist was to convey the social status of the model.

The social characteristic of the Buddhist patriarch in the portrait reproduced here is manifest in the full front view of the model, in the immobile heaviness of his figure and in the detailed treatment of the costume and the insignia indicating the priest's rank. The stern and expressionless face with its clear-cut pattern of wrinkles betrays a strong and imperious character, although the'rigid conventions of formal portraiture, permitting a certain degree of indi-vidualization, left no room for any psychological analysis of the sitter.

Dish

China. 16th century

Porcelain, painted in cobalt blue, iron red and enamels.

Diameter 30 cm. lnv. No. 6306 I

Received in 1947 from the Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga Association, Moscow.

The dish comes from a workshop of the town of Chintechen renowned for its porcelain. From the 15th century the Chintechen craftsmen began to use new methods of decoration in which underglaze painting in cobalt blue was supplemented with over-glaze ornamentation in green and yellow enamels and iron red. This style was referred to as dou tsai (the struggle of colours). The manufacture of such articles involved a complicated and laborious process in the course of which part of the decor was painted in cobalt blue, then the article was covered with transparent glaze and fired at 1400 degrees Centigrade, enamelled and painted in iron red, and, finally, fired again at a lower temperature.

The decoration of the dish represents two dragons and two fantastic birds, Fenghuangs, which personified the duality of nature. (In Chinese poetry, incidentally, Fenghuang also symbolized a happily married couple.)

The first hallmarks, or reign-marks, appeared on Chinese wares during the rule of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). They contained the name of the dynasty and the emperor's assumed name (his real name was a taboo whose violation was punishable by death). The reign-mark on this dish gives the name of Emperor Wang Li (1573-1620).

Vase

China. Early 18th century

Porcelain, painted in cobalt blue and enamels.

Height 35 cm. Inv. No. 1781

Received in 1919 from the Art and Industry School (formerly the Stroganbv Art School), Moscow.

Chinese porcelain of the 17th and 18th centuries was distinguished for its particular whiteness, the refinement and variety of its shapes and its colourful ornamentation. Among the most popular motifs was the motif of flowers symbolizing the seasons of the year. Each of the four sides of this vase is painted with blossoming plum branches, peonies, lotus-flowers and chrysanthemums. The bamboo motif on the neck of the vase symbolizes moral strength and an ability to withstand misfortunes. The painted decor is performed in the "black family" style: the biscuit is covered with black enamel which, in its turn, is painted with green enamel; after firing, the spaces left uncoloured are filled in with brown, yellow, green and violet enamels. The process ends in a second firing. The reign-mark on the bottom of the vase gives the name of Emperor K'anghsi (1662-1722).

Box

Peking. China. 17th century

Papier-mache and carved red lacquer.

Height 22 cm, diameter 29 cm. Inv. No. 24941 КП

Received in 1923 from a private collection, Moscow.

The red lacquer wares produced at the Peking workshops covered a wide range of shapes and functions: imperial thrones, furniture, screens, trays, boxes, vases and so on. They were usually embellished with elaborate carved designs representing architectural landscapes, genre scenes, flowers and birds. The sap of ch'ishu trees, grown in the southern and central parts of the country, was used as the basic ingredient for the lacquer. The poisonous exhalations of the sap caused grave professional diseases among craftsmen. The process of making lacquer articles consisted of several operations and was rather long and complicated. In its fluid state, the lacquer was combined with natural cinnabar and applied to the wooden or papier-mache foundation in as many as a hundred coats. While the last coat was still wet, the surface of the article was covered with thin paper. The pattern drawn on it was transferred onto the lacquer with a needle. The carving was done in a damp room so that the lacquer would not harden too quickly. The entire process could sometimes take several months.

The decor of this presentation box consists of a central scene executed in high relief and showing a palace wall against an architectural landscape and of minute meandric patterning encircling it. Like some early Peking lacquer objects (11 th to 16th centuries) the box is dark red with a brownish tinge. The many-layered carved design accounts for a subtle play of light and shade on the surface of the box.

Gown

China. Late 19th century

Brocade, with embroidery.

162 × 142 cm. Inv. No. 5723 I

Acquired in 1976 from a private collection.

In medieval China such brocade gowns with embroidery and the cuffs cut in the form of hooves (paotsu) were assigned a specific role: they were meant for the dignitaries' wear and as presentation pieces to the rulers of neighbouring states. During the Ch'ing dynasty (1644-1911) the yellow colour- the colour of late summer, the harvest season, and the earth-was used exclusively in royal attire, and for common people to wear yellow was a crime punished by death. The ornamentation of the traditional Chinese robe was extremely significant. It consisted of two parts. In the early Middle Ages, the decor of the upper part of the robe worn by the emperor incorporated the twelve Imperial symbols, or shiherchang (twelve was a symbolic number because of the twelve signs of the zodiac and twelve months in the year). These symbols had formerly been used to adorn only ritual robes worn during religious sacrifices, but during the Ch'ing period they found their way into the decorative pattern of formal court costume. Shiherchang symbols included the sun, the moon, the Great Bear, the mount K'unlun- "the Axis of the World", a pheasant, cups from the temple of ancestors, grain, fire, dragons, and, finally, the meander-like motif fu-fu (its basic element represents a stylized axe-a symbol of the juridical power of the emperor). The wave-like pattern along the hem symbolized the union of the two rival forces of nature-Yang and Yin.

The present late-19th-century gown made for a government official is adorned only by several benevolent symbols.

Panel: Presentation of Gifts to the Goddess Shi Wangmu

China. 18th century

Silk, with embroidery.

270 × 160 cm. Inv. No. 15613

Received in 1969 from the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

Embroidery is a traditional Chinese craft, whose major centre has for centuries been the town of Suchou. Embroideries produced there adorned screens, curtains, decorative panels, coverlets, clothes and so on. Many-layered embroideries were a very common type, just like the hsuhua (needle painting)-large decorative panels representing various scenes, done in satin stitch in combination with a fine knot stitch. The aesthetic quality and pictorial expressiveness of embroideries justify their comparison with paintings proper. The silk threads of a vast variety of subtle tints created an illusion of volume and produced a chiaroscuro effect. The pattern of the above panel is embroidered in satin stitch on a shimmering golden background, done in threads entwined with gold foil. In spite of the minute treatment of pictorial details the panel creates a monumental and predominantly ornamental effect. Such embroideries adorned the walls of the reception rooms in the palaces of the Chinese nobility. The panel shows the goddess Shi Wangmu sitting in the magic garden of peach-trees and receiving gifts from other deities.

Vase

China. 19th century

Carved pink quartz.

Height 39.5 cm. Inv. No. 10156 I

Acquired in 1953.

At the time of the Ch'ing dynasty (1644-1911) luxury articles made of semiprecious stones (agate, jade, rock crystal, chalcedony, pink quartz, etc.) were a common feature of rich Chinese households. Vases, incense-burners, cups, brush-holders, small-scale decorative sculpture, signebrings and amulets present a broad range of forms and decorative motifs. The making of stone articles required a refined artistic taste, a high proficiency level and, last but not least, patience. Polishing alone could sometimes take years. Chinese jewellers had a feel for stone and knew how to emphasize its natural beauty and colour. In doing so, they had to overcome its hardness and to manifest a virtuoso technique of carving.

The pink quartz-the stone of which this vase is made-was highly valued for its alleged healing properties. It was a symbol of health and physical strength. The subject used in the decor of the vase-boys climbing a peach-tree-is traditional for Chinese art. It is connected with a popular Chinese wish for well-being -the wish for a long life and virtuous sons.

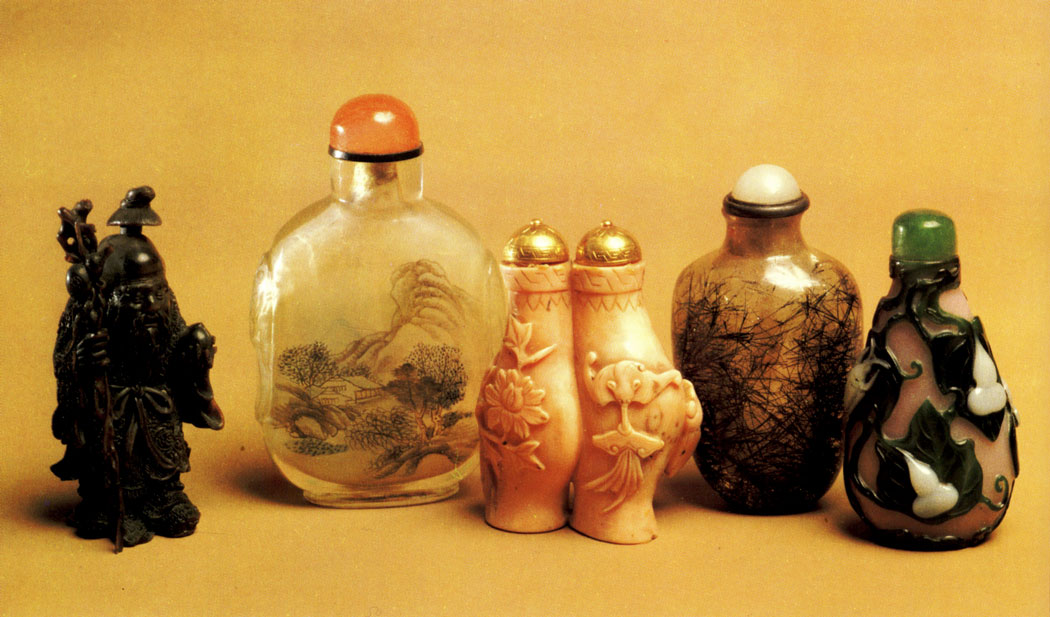

Snuff-boxes

China. 18th and 19th centuries

Shouhsing, the Deity of Happiness and Longevity.

Carved horn.

Height 6.5 cm. lnv. No. 7355 I

Donated in 1949 by Dmitry Melnikov.

Snuff-box with a landscape. Glass, painted on the inside.

Height 7.2 cm. Inv. No. 6753 I

Donated in 1949 by Dmitry Melnikov.

Double snuff-box with a bat. Carved coral and engraved gold.

Height 5.5 cm. Inv. No. 7337 I

Donated-in 1949 by Dmitry Melnikov.

Snuff-box. Carved agate.

Height 6.4 cm. Inv. No. 1402 I

Received in 1934 from the Museum of the Peoples of the USSR, Moscow.

Snuff-box with a pumpkin. Carved three-layered glass.

Height 6 cm. Inv. No. 6747 I

Donated in 1949 by Dmitry Melnikov.

Chinese snuff-boxes were usually made in the form of small bottles with stoppers to which tiny ivory or metal spoons were attached. Snuff-boxes first appeared in China in the reign of Emperor K'angshi (1662-1722) and later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, became very common. They were usually made of semiprecious stones-agate, chalcedony, cornelian, jade, rock crystal and lapis lazuli. Ivory, wood and lacquer were also used. Sometimes, although rarely, snuff-boxes were made of porcelain and metal. The extant examples of snuff-boxes reveal a rich creative imagination and the superb skill of Chinese craftsmen, as well as their ability to bring out the natural beauty of the material, especially stone, to display to the best advantage its colour, and the veins and varicoloured stains that covered its surface. Snuff-boxes made of glass were embellished with exquisite painted designs applied with the help of a special brush to the inside surface. Another type of decoration was engraving on glass, imitating stone carving. In the province of Shantung snuff-boxes were sometimes made of two-layered glass, with a coloured floral pattern standing out against a background of pale-coloured glass.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'