Uzbekistan

Badia bowl

By Balta Vaisov (1893-1957). Village of Khanki, Uzbekistan. 1950s

Clay, painted and glazed.

Height 9 cm, diameter 34 cm. Inv. No. 4302 III

Received in 1958 from the Museum of Ceramics in Kuskovo, Moscow.

Due to a somewhat isolated position of Kwarasm as regards the rest of Central Asia, its social, historical and cultural development went along its own specific path which resulted, among other things, in the emergence of a number of distinctive features of local art in general and of ceramics in particular. The decor of Kwarasm pottery is characterized by a monumentality and expressiveness of patterns and by a traditional purity of style. It is usually based on elaborate geometricized floral motifs going back to medieval antecedents and observable also in the architectural majolica ornamentation and wood-carving of Kwarasm of the 19th and 20th centuries. Badia, a deep and massive bowl on a short ring-shaped base, is a distinctly local type of earthenware unparalleled elsewhere in Uzbekistan. It has the two-fold function of a dish and of a bowl and can be used as either or both alternatively.

Balta Vaisov, one of the most interesting masters in Uzbekistan, gave his own touch to the traditions of Kwarasm pottery.

A laconic blue-and-white design decorates the bottom of the bowl. Its centre is decorated with a traditional madokhil pattern formed of four lancet arches. It is surrounded by interlacing stylized floral patterns. The badia's design resembles the majolica decor of Kwarasm architecture.

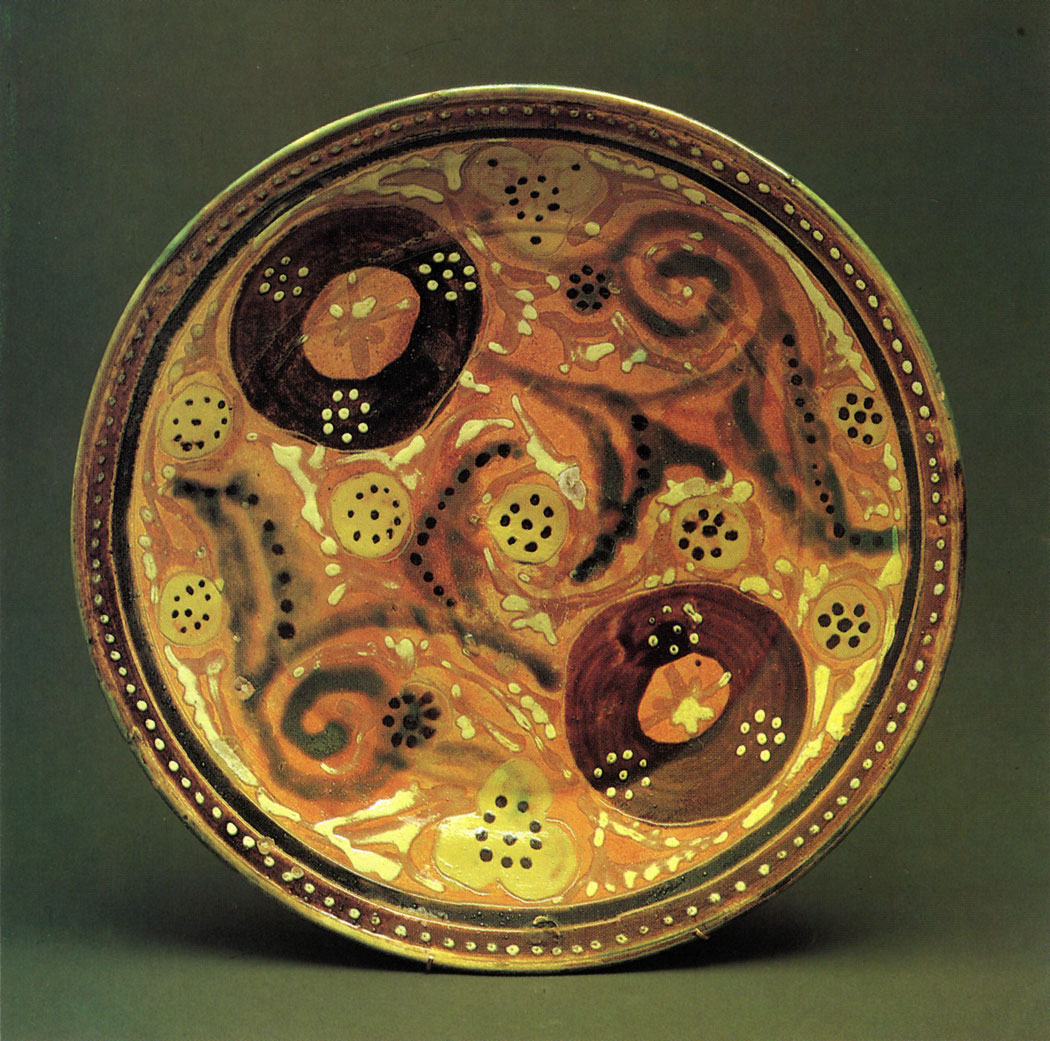

Liagan, a pilau dish

By Abdukarim Khazratkulov (1890-1968). Shakhrisiabz, Uzbekistan. 1962

Clay, with slip decoration, glazed.

Height 5.5 cm, diameter 32.5 cm. Inv. No.4797 III

Acquired in 1963 from the potter. First publication.

Abdukarim Khazratkulov, one of the most talented and well-known representatives of the contemporary Shakhrisiabz school of pottery-making, first learned his craft from his father and uncle, also descendants of a potter's family, then from the masters of the village of Gijduvan near Bukhara, and later trained over forty pupils himself.

Compared with the celebrated medieval ceramics from Afrasiab, contemporary wares seem thick-sided, heavy and somewhat crude. However, classical traditions are apparent in the combinations of colours, in the compositional arrangement and details of ornamental motifs. The laconic design of Khazratkulov's dish is done in a free and unrestrained manner; the colour scheme is based on the interplay of golden-brown hues. The ornament consists of several simple elements: circles, scrolls and dots (potters called this design bull's eye). Khazratkulov's essentially modern style is characterized by brilliant decorativeness and unaffected simplicity.

Aftoba water vessel

Kokand, Uzbekistan. Second half of the 19th century

Copper, chased, engraved and nielloed, with paste inlays.

Height 29 cm, diameter 23.5 cm. lnv. No. 8711 III

Acquired in 1979 from a private collection. First publication.

In the 19th century, particularly towards its end, ornamented copperware gradually lost its functional character and began to play a purely decorative role-it was used for adorning the mekhmonkhana, the guest room in the house of a well-to-do citizen. It became a mark of social and financial prestige. Bird-shaped vessels have antecedents in early medieval

Central Asiatic art (3rd-7th centuries). As for copper articles, in the 19th century, this shape was no longer common, but in ceramics it was favoured up to the present century. This zoomorphic motif presumably takes its origin in ancient pre-lslamic religions and myths. In the 19th century, it was thought to possess the powers of goodwill and protection. The vessel reproduced here is undoubtedly the work of talented masters. It is not big, but its proportions are perfect and its shape is expressive. The traditional plant motif, the slender convolvulus islimi, twines round the vessel's body and neck. Numerous sprouts and swirls echo the rounded forms of the vessel itself.

Washing-set: dastshui wash-basin and aftoba ewer

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Second half of the 19th century

Copper, chased and engraved, with turquoise inlays.

Height 4.5 cm, diameter 39.5 cm. Inv. No. 201 III (wash-basin).

Height 50 cm, diameter 12.5 cm. Inv. No. 200 III (ewer)

Received in 1927 from the Art and Industry School (formerly the Stroganov Art School), Moscow.

Decorative metalwork in Central Asia is a craft of long standing and time-honoured traditions. Far back in antique times it had reached a high level of artistic skills, and the Middle Ages saw the period of its true glory. The traditions and secrets of metal-work were passed on from one master to another, and the forms and the decor of metalware were elaborated through the centuries. Until the 19th century the main material had been bronze, which in the 19th and early 20th centuries was superseded by red and yellow copper. The chased copper articles were richly decorated with exquisite engraved plant ornamentation. There were a number of manufacturing centres producing copper articles which, though they had much in common, also possessed distinctive local features. Among the best-known centres were Bukhara, Kokand, Samarkand and Karshi.

A washing-set was an indispensable part of the dowry of any bride from a well-to-do family. It consisted of two objects-a ewer and a wash-basin. The wash-basin was used not only for washing hands, but also for ritual ablutions. It usually had a round shape and an openwork lid. The rim was wide and scalloped. In the middle of the second half of the 19th century such wash-basins, besides their traditional engraved ornamentation, were also decorated with large chased lobes and plant designs. Aftobas, large ewers with beautifully curved handles and elaborate floral decoration, have austere forms and harmonious proportions. The present ewer answers this description to the last detail. It is exquisitely decorated with an intricate pattern, which covers its entire body, and set with blue turquoise. Its rich decor is based on traditional elements.

Bracelet

Kokand, Uzbekistan. 19th century

Silver, nielloed and engraved, with corals.

Height 3.2 cm, diameter 6.2 cm. Inv. No. 1241 III

Acquired in 1929 from a private collection.

Gold, silver, turquoise and rubies were mined in Central Asia way back in antiquity, which gave rise to favourable conditions for the development of the craft of jewellery-making. By the 19th century jewellery-making had inherited a large repertory of techniques and a variety of forms elaborated in the course of its thousand-year history. The major centres of jewellery-making in Central Asia were Bukhara, Kokand and Khiva, the capitals of the three khanates which appeared in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The kinds of ornaments worn by a person were determined by his position and age, by the type, cut, style and colour of his costume. Ornaments for festive occasions were, naturally, most luxurious. The set worn for such an occasion included twin bracelets, earrings, necklaces, brooches, temple pendants, etc. Such assemblages of jewellery became fashionable in the second half of the 19th century.

Jewellery-making was particularly favoured in Uzbekistan. Women, naturally, were the most devoted customers. "While but a single woman remains on earth, the jeweller's craft will not die," ran an Uzbek proverb of that time.

One of the most ancient and popular types of female ornaments were bracelets. The bracelet reproduced here (one of a pair) belongs to the type of closed bracelets. Its lock is provided with a chain with corals, and the bracelet itself is decorated with the exquisite islimi pattern standing out against a black background.

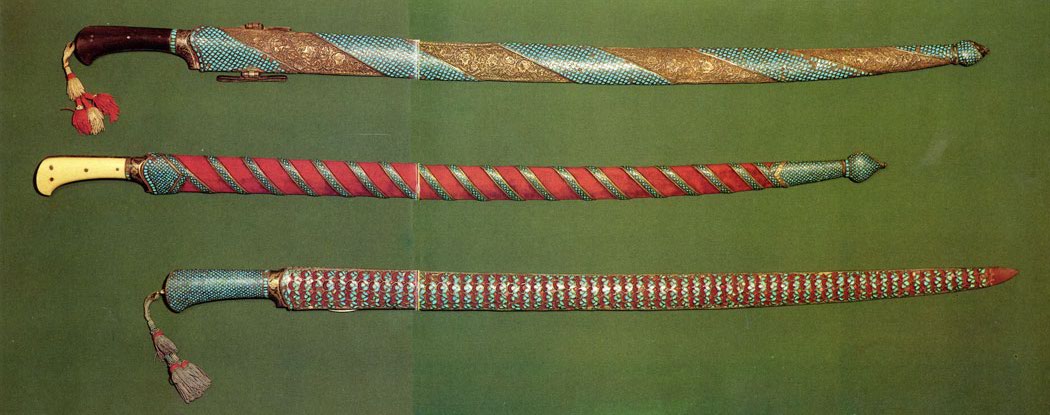

Sabres in scabbards

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. 19th century

Steel, silver gilt, turquoise, bone.

Length 101 cm. Inv. No. 3404 III

Received in 1949 from a private collection.

Steel, velvet, turquoise, bone.

Length 92 cm. Inv. No. 2280

Received in 1930 from a private collection

Steel, turquoise, enamel.

Length 90 cm. lnv.No.3705 III

Received in 1952 from the Hermitage, Leningrad. First publication.

The blades of sabres were made of high-quality steel and often decorated with engraved ornamentation. The scabbards were usually decorated with great lavishness. They were made of precious materials-white or gilded silver adorned with chased or engraved floral patterns. They were also frequently decorated with polychrome enamels and set with precious or semiprecious stones- diamonds, corals and polished turquoise which, according to local beliefs, brought luck.

In the 19th century, cold steel practically lost its primary function as a weapon and became merely an attribute of men's costumes on festive and ceremonial occasion. In the khanates of Bukhara, Kokand and Khiva such sabres were granted as rewards to courtiers and presented as gifts to foreign ambassadors and rulers.

Earrings

Uzbekistan. 19th century

Silver, with granulation; cornelian, turquoise and mother-of-pearl.

Length 12 cm. Inv. No. 2448 III

Acquired in 1937 from a private collection.

Earrings were among the most popular female personal ornaments. Their shapes and sizes varied widely, and they were lavishly decorated, with precious and semiprecious stones. Uzbek jewellers gave preference to red, green, blue or white gemstones which set off the dark skin of southern women to the best advantage.

These earrings have an anthropomorphic form and at the same time are reminiscent of some exotic flowers. They are generously adorned with precious stones. The decorative effect is enhanced by the contrast between turquoises of different shades- from sky blue to greenish blue-and golden-red cornelians.

Khalkah earring

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. 19th or early 20th century

Silver, with filigree and granulation; emeralds, rubies and pearls.

Length 12.3 cm. Inv. No. 3972 III

Received in 1954 from the Museum of Ceramics in Kuskovo, Moscow. First publication.

In the 19th and early 20th century, Bukhara jewellers produced several types of earrings. Earrings of the type reproduced here-large and heavy, decorated with rubies, emeralds and pearls-were worn by brides and young married women of rich Bukhara and Samarkand families.

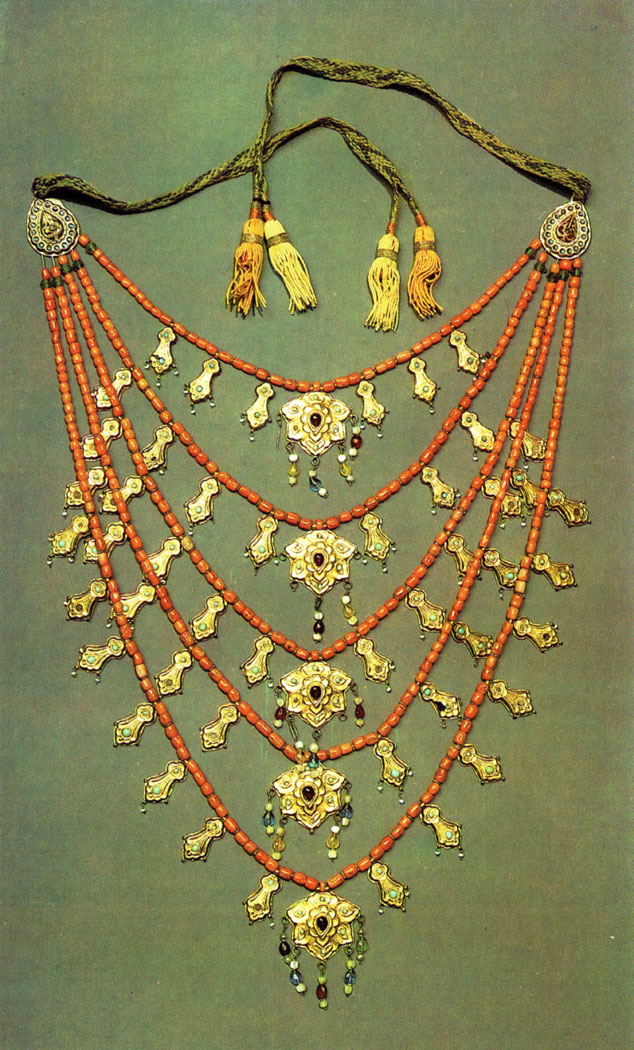

Djiviak necklace

Tashkent, Uzbekistan. 19th century

Silver, gilt and stamped, with glass studs and corals.

Length of the strings 31, 41, 51, 61 and 73 cm respectively. Inv. No.4194 III

Acquired in 1958 from a private collection.

Uzbek jewellers produced necklaces which often consisted of numerous strings of corals and of all kinds of dangling and jingling pendants.

This necklace is composed of five strings of corals with gilded leaf-shaped pendants. In the middle of each string there is a medallion shaped as a flower rosette.

Khalkai-mardjon earrings and necklace

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. 19th century

Silver gilt, with filigree work and corals.

Length 9 cm, diameter 2.5 cm. Inv. No. 4425 III (earrings)

Silver, engraved, with corals.

Length 25.5 cm. lnv. No. 4421 III (necklace)

Acquired in 1959 from a private collection.

These earrings, one of the commonest types in Bukhara, are in the form of a ring, with a filigree pal-mette inside the ring and pendants in which corals alternate with silver beads.

Neck ornaments worn by women for festive occasions, weddings or religious holidays, have been made in a great variety of shapes. The simplest form favoured in Bukhara was a coral mardjon necklace.

This necklace belongs to a type of Bukhara ornaments with a characteristic combination of silver beads and corals.

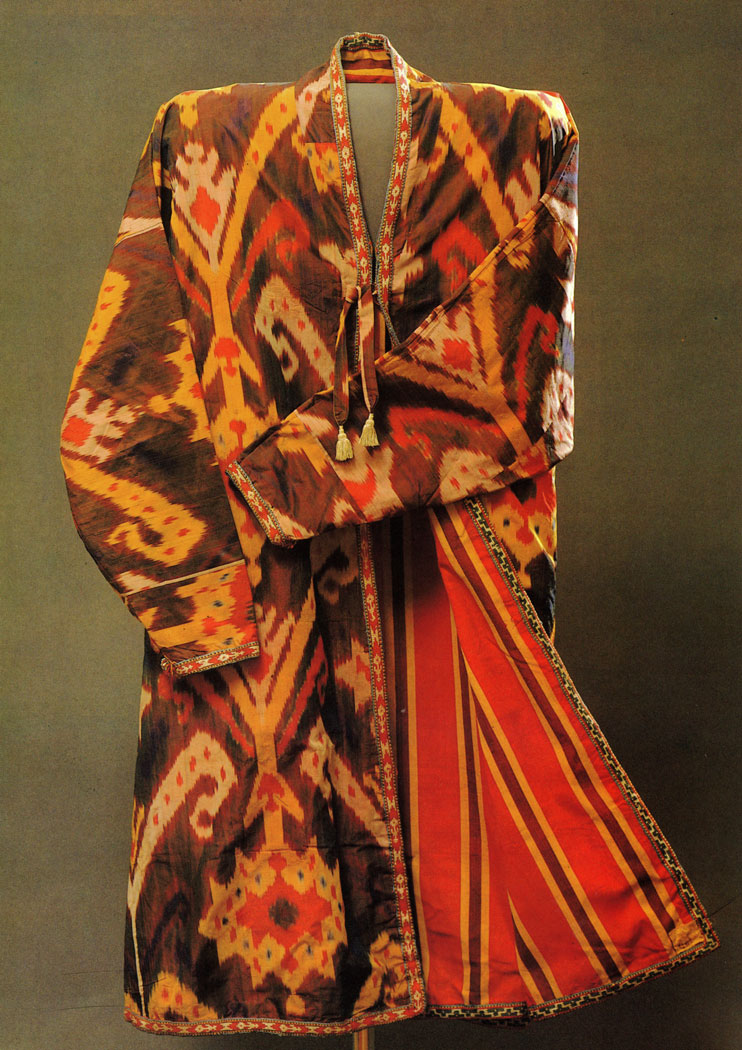

Chapan reversible robe for ceremonial purposes

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. 1870s

Hand-woven silk.

Length 146 cm, cuff to cuff measurement 220 cm. Inv. No. 2560 III

Acquired in 1937 from a private collection. First publication.

The robe is of a characteristic Bukhara cut-a loose, long, unfastened garment without shoulder seams, with long, wide sleeves.

Such robes came into fashion in Bukhara in the last quarter of the 19th century. The citizens of Bukhara were often referred to as "the Parisians of Central Asia". They knew the art of dressig simply and not expensively but elegantly, and they also knew how to wear their long loose robes with inimitable ease and refinement. The robe is reversible, and the cut of both sides is identical. The right side is made of fine first-class Bukhara silk of close texture-shoi. The large-patterned design of the fabric goes back to ancient Central Asiatic antecedents-to silks and brocades from Soghdiana. The wrong side is made of dark cherry-coloured silk with wide vertical yellow and wine-coloured stripes. These vertical stripes emphasize the length of the garment. The stiff close-textured fabric sets off the shape of the long flowing robe to the best advantage, imparting to its owner a stately and imposing look which was greatly appreciated by the Bukhara nobility.

The neck, lapels, hem and the cuff-line of the sleeves on both sides of the robe are trimmed with a narrow patterned tape. The strings terminate in white tassels-an indication of social rank. Such robes were presented to high dignitaries, courtiers, military and civilian officials. In the second half of the 19th century and up to the early 20th, citizens of the Bukhara emirate who held those posts received such robes together with their annual wages.

Skull-cap

Shakhrisiabz, Uzbekistan. 19th century

Cotton, with chain-stitch embroidery in silk and red wool, trimmed with djiyak braid.

Height 18 cm, diameter 25.5 cm. Inv. No. 23107 КП

Acquired in 1971 from a private collection. First publication.

A skull-cap is a small tight cap which was particularly common in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. The shape, colour and ornamentation of skull-caps were determined by long-established traditions and local styles.

This skull-cap belongs to the cone-shaped type of headgear. It is the earliest and most conventional of all Central Asiatic skull-caps. It was common in Tashkent, Samarkand, Shakhrisiabz, Karshi, Bukhara and Surkhan-Darya. Nowadays this type can be found only in museum collections. The cap is made of home-woven cotton in dark blue with narrow white stripes. The entire surface of the cap is embroidered in finest chain-stitch-the oldest and commonest stitch in Central Asia. The minute "chains" of the embroidery form a dense carpet-likegeometric pattern. The opposite sectors of the cap are decorated with identical designs but in different colours.

Judging by the style of decoration and techniques used in making the cap, it can be placed as one of the earliest extant articles with satin-stitch embroidery from Shakhrisiabz.

Ceremonial horse-cloth

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Mid-19th century

Velvet, with embroidery in gold and silver thread.

222 × 148 cm. Inv. No. 1484 III

Acquired in the late 1920s. First publication.

In the 19th century, Bukhara remained practically the only place in Central Asia which still produced embroideries in gold and silver thread. This traditional ancient handicraft combined elements of the jeweller's art and embroidery proper. In contrast with most types of embroidery, gold-thread embroidery was almost exclusively the prerogative of men. Articles embroidered in gold thread-clothes, horse-cloths, etc.-were produced in a number of private workshops and those appointed to the emir's court. The right to wear gold-embroidered clothes belonged only to the members of the royal family, to the highest court officials and to the cream of the Bukhara aristocracy.

This horse-cloth was intended for a high nobleman's ceremonial turn-out. Its velvet background is entirely covered with relief gold and silver plant patterns with a vase of flowers in the centre.

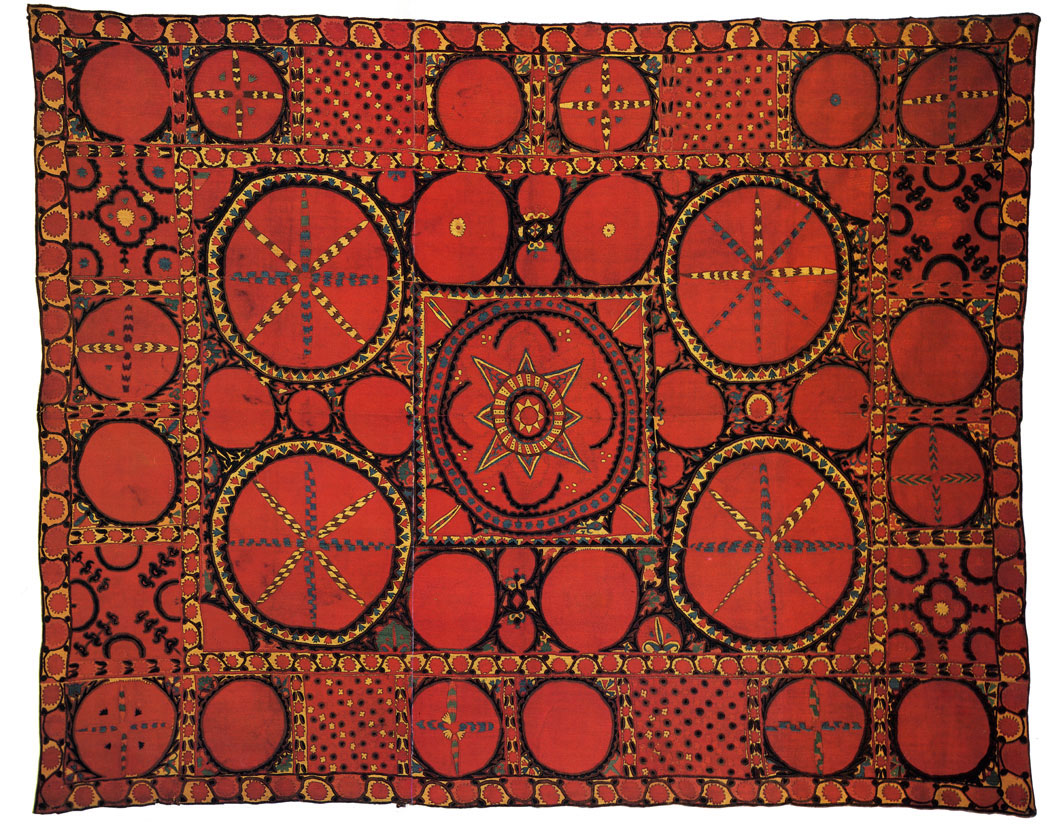

Paliak decorative panel

Pskent, Uzbekistan. Second half of the 19th century (before the 1870s)

Cotton (karbos), with satin-stitch embroidery in silk and wool.

265 × 217 cm. Inv. No. 6476 III

Acquired in 1971 from a private collection. First publication.

In Tashkent and the Tashkent region the largest embroidered panels were called paliaks. This paliak comes from a small village of Pskent situated 46 km from Tashkent. Like other paliaks from Pskent, it is on the whole close to the articles produced in Tashkent, but at the same time it is not devoid of certain local traits. Both the central part of the panel and its border are divided into squares filled either with round rosettes of various sizes or small-scale geometric patterns. The largest rosette is in the centre of the panel; it was traditionally associated by local embroideresses with the sun or the moon. In fact, the composition as a whole symbolizes the firmament with the sun (or the moon) and the stars. In its monumental decorative treatment, its geometric motifs, its monochromatic colouring, and its symbolism and style the paliak is evocative of the nomads' rugs. As a matter of fact, the simple and well-balanced rhythms of its ornamentation were very likely derived from the ancient traditions of Uzbek art in the nomadic period.

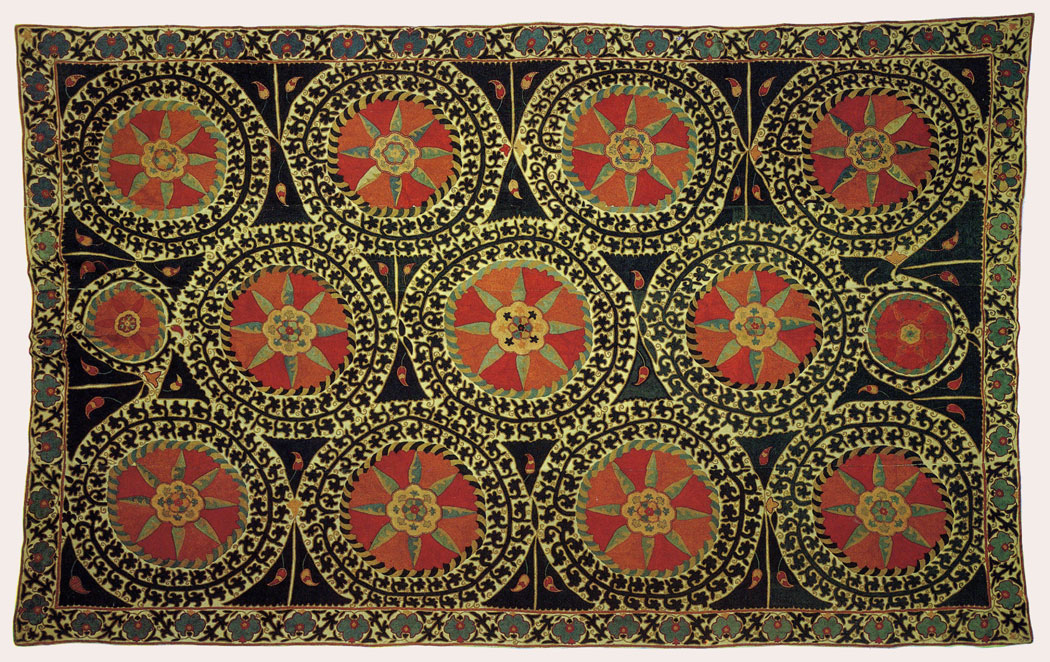

Suzani decorative panel

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Second half of the 19th century (before the 1870s)

Cotton (karbos), with chain-stitch embroidery in silk.

162 × 260 cm. Inv. No.4809 III

Acquired in 1963 from a private collection.

The basic element of this embroidered panel is the circle. A strongly stylized floral design fills the entire surface of the panel. Such uniformly repeated patterns are very common and have well-established traditions in art of many regions, of which Central Asia is one. The principal expressive device of this panel is the colour which is clearly defined in the rosettes. The nuances of colour enrich and enliven the simple ornamental forms and impart a certain rhythmical variety to the composition.Embroideries from Bukhara and the adjoining regions present a wide range of various shades of red-from warm orange to cool crimson-set off by different shades of green.

The present embroidery is almost devoid of local colours. Instead, complicated shades prevail. Due to the use of natural pigments, the colour combinations are exquisitely reserved, deep and harmonious despite the apparent intensity and saturation of separate patches. The artistic merit of the panel to a great extent also depends upon the excellent technique of chain-stitch embroidery. This method of stitching creates a visual effect of relief mosaic-like decoration and adds another picturesque touch to the article.

This suzani is a splendid example of painterly style in embroidery. The unevenly dyed silk threads used for the stitching account for the vibrancy and saturation of colour.

Suzani decorative panel

Nurata, Uzbekistan. 19th century

Cotton (malla) and silk, with couched satin-stitch embroidery in untwisted silk (outlines in feather-stitch).

284 × 175 cm. Inv. No. 1107 III

Acquired in the 1920s from a private collection.

This suzani possesses all the most typical traits of embroidery from Nurata-small patterns freely scattered over the background with large spaces left vacant; quiet and reserved combinations of colour devoid of any clashes or sharp contrasts; a large repertory of exquisitely treated floral motifs and, finally, the presence of representational motifs, such as stylized vessels and birds. The decor of this suzani is arranged around the well-defined central composition combining two traditional Nurata patterns-"four branches and one moon" and "branches".

The technique used in the production of suzanis is rather complicated and rarely found in Central Asiatic embroideries-the satin-stitch embroidery lies over the foundation of raw silk. Such a technique was used in the 18th- and 19th-century Kaitag embroideries from mountainous regions of Daghestan.

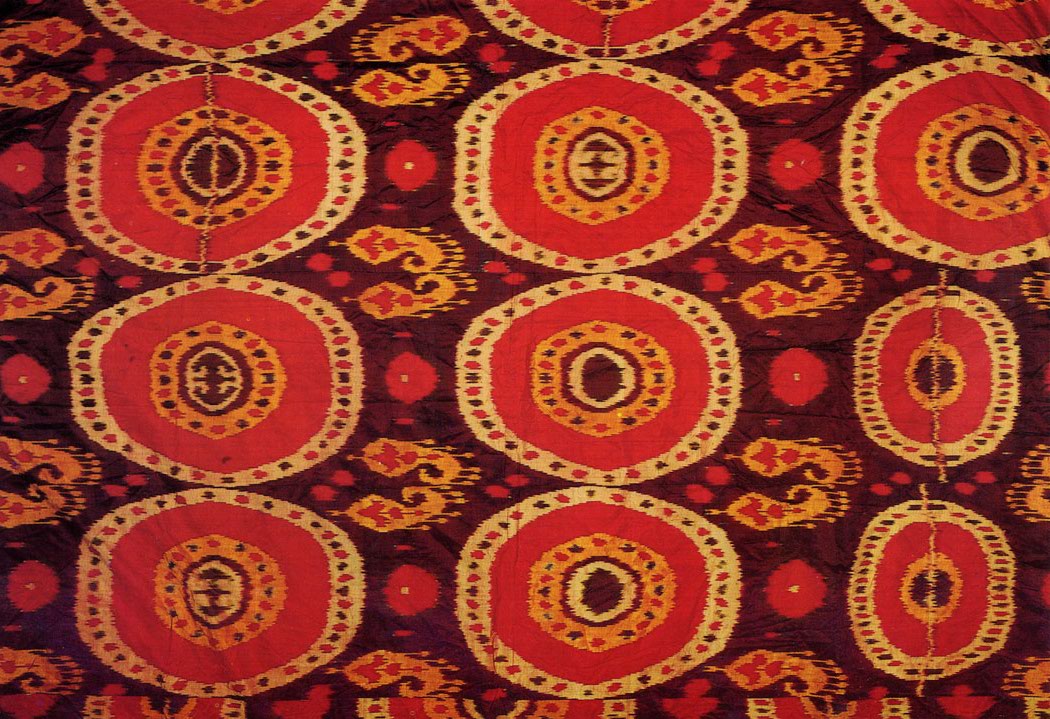

Decorative panel (fragment)

Bukhara, Uzbekistan, First half of the 19th century

Hand-woven semi-silk fabric (adras), home-dyed and glazed.

240 × 168 cm (consists of several widths of fabric, 30 cm wide each). lnv. No. 2557 III

Acquired in 1937 from a private collection. First publication.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Bukhara and the adjoining districts were the major textile-producing areas of Central Asia.

In terms of techniques and decorative devices, the Uzbek and Tajik textiles of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries possessed a number of distinctive features. Ornamental patterns were produced by a negative dyeing, in which certain lengths of the warp were marked out as not subject to dyeing and the rest was alternatively dipped in different dyes in accordance with the desired polychrome design. Due to the inevitable overlappings of colour throughout the length of the warp the contours of the resultant patterns were somewhat blurred and reminiscent of clouds reflected in water. The Uzbeks call textile produced in this manner-abr fabrics.

The abr fabrics of the 18th and early 19th centuries were usually rather narrow-from 25 to 40 cm wide. One interesting variety of this type of textile is adras-the fabric with a silk warp and cotton weft decorated with a dimly outlined, "clouded" pattern. It is a densely woven fabric with a ribbed texture produced by the rough cotton weft. It has a glossy surface with iridescent moire patterns resulting from the traditional glue treatment and subsequent hammering. Panels made of adras were designed for interior decoration and used as bedspreads and wall-hangings.

The panel reproduced here is a fine example of the Bukhara-style fabrics. The hues produced by natural pigments are soft and deep, the panel itself is however fairly picturesque. The colouring as a whole is dominated by the colours of equal intensity and saturation, and the design possesses a dynamic vividness due to the overlappings of dyes.

Decorative panel (fragment)

Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Second half of the 19th century

Hand-woven silk fabric (shoi), hand-dyed.

226 × 161 cm (consists of several widths of fabric, 36 cm wide each). Inv. No. 802 III

Acquired in 1936 from a private collection. First publication.

The panel consists of four widths of Bukhara-made abr silk. The fabric is densely woven, crisp and glossy, the colouring is brilliant and intense. The ornamental motifs used by Bukhara weavers for decorating silks in the second half of the 19th century were generally not very elaborate. Well-defined and simple stylized plant designs prevailed, e.g. the apple motif (alma), the almond motif (bodom), the pomegranate motif (anor) and floral motifs. These were sometimes complemented by stylized representations of personal ornaments, like the tillakosh diadem, the tumor amulet, various earrings and temple pendants of all kinds.

This panel, along with many other Bukhara-made textile articles, displays an original treatment of traditional motifs arranged into a picturesque and eyecatching ornamental composition.

Bridegroom

By Alexander Nikolayev (Usto Mumin; 1897-1957). Uzbekistan. 1920

Tempera on paper.

30 × 26.5 cm. Inv. No. 2206 КП

Donated in 1970 by E. Marchenko-Mordvinova, Moscow.

An Honoured Artist of Uzbekistan, Alexander Nikolayev was born in Voronezh and studied at the Second Free Art Studio in Moscow (1918-19) under Kazimir Malevich. From 1920 he lived and worked in Tashkent.

Alexander Nikolayev was one of the oldest contemporary artists of Uzbekistan. He made a considerable contribution to the formation of the local artistic school and, in general, to the development of national art. In his works Alexander Nikolayev strove to create ideally harmonious images. He found his plastic ideal in the fusion of pictorial principles of Russian icon-painting and the medieval Oriental miniature. The Bridegroom is one of his early works where his graphic skill and his mastery of the expressive line are revealed with utmost clarity.

Caravan III

By Alexander Volkov (1886-1957). Uzbekistan. 1921-22

Tempera, varnish and sand on canvas mounted on plywood.

106 × 141 cm. Inv. No. 29780

Acquired in 1977 from the East and Russian Art Exhibition, Moscow.

A People's Artist of Uzbekistan, Alexander Volkov was born in Skobelev (now Fergana) and studied at M.Bernstein's studio in St. Petersburg (1910-12), took lessons from Vladimir Makovsky, Nikolai Roerich and Ivan Bilibin, and later studied at an art school in Kiev (1912-16) and attended the studio of Fiodor Krichevsky. He was a teacher at art schools and studios in Tashkent (1916-26) and at the Republican Art School of Tashkent (1929-41, 1944-46). He lived and worked in that city. Alexander Volkov belongs to the galaxy of the most celebrated Soviet painters. His name is associated with the appearance and development of easel painting in Uzbekistan. The artist evolved his own pictorial system based on certain similarities between Western European and Central Asiatic artistic traditions.

His Caravan III is a telling example of the artist's stylistic pursuits at the early stage of his career when he tried to convey the idea of the fluctuation and integrity of all that exists in time and space. The schematic treatment-in the manner of ornamental motifs-of the geometrically stylized forms (sandhills in the desert, camels and camel-drivers) seems both two- and three-dimensional at the same time. The effect of motion is achieved with the help of a clear-cut rhythm. The complicated, yet noble colour-scheme follows the example of the traditional colouring of Central Asiatic carpets and textiles.

Fruit Vendors

By Alexander Volkov (1886-1957). Uzbekistan. 1927

Oil and tempera on canvas, varnish.

102 × 102 cm. Inv. No. 6386 III

Acquired in 1971 from Alexander Volkov's one-man show, Moscow.

This picture represents the intermediate period of the artist's creative career. In those years Alexander Volkov changed his attitude to the Western European artistic legacy and developed a more profound insight into the cultural traditions of the East. In his Fruit Vendors Volkov, endowing his characters with mythological quality, reveals his inclination towards monumentality. A routine market-place scene in the picture breaks through the confines of a concrete and trivial subject and acquires a philosophic and poetic meaning. The characters of the scene seem to be descended from antiquity. The clarity of compositional and plastic treatment and the integrity of the picture make it a worthy example of the most "privileged" form of visual art-easel painting-and at the same time endow it with a resemblance to the crude signboards outside fruit shops in Asiatic towns.

Nomad Camp

By Ural Tansykbayev (1904-1974). Uzbekistan. 1931

Oil on canvas.

106 × 106 cm. Inv. No. 1654 III

Received in 1935 from the State Purchasing Commission (acquired in 1934 from an exhibition of Uzbek painting in Moscow), Moscow.

A People's Artist of the USSR, Ural Tansykbayev was born in Tashkent. He studied at a private studio in Tashkent (1924-28) and at an art school in Penza (1928-29). Later he lived and worked in Tashkent.

Ural Tansykbayev is one of the best-known Uzbek artists. The Museum possesses several of his early works characteristic of the pursuits of his own pictorial idiom and creative individuality. Nomad Camp rates among the best and most expressive paintings by the artist. It attracts the spectator with the epic role of the landscape and the poetically meaningful imagery.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© MUSEUMS.ARTYX.RU, 2001-2021

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'

При использовании материалов сайта активная ссылка обязательна:

http://museums.artyx.ru/ 'Музеи мира'